Rwanda

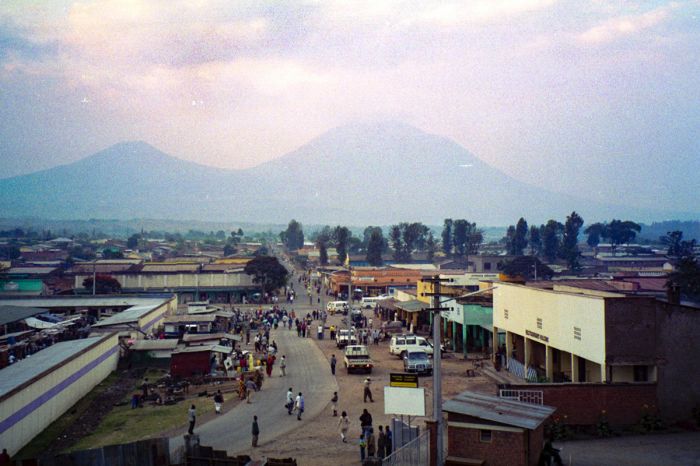

Region Links: Rwanda Volcanoes

Highlights

- Gorilla trekking in the mountains is an amazing wildlife adventure.

- Akagera National Park offers Big Five safaris in a savanna ecosystem.

- The Nyungwe Forest offers diverse primates and chimpanzee trekking.

- Rwanda is considered one of Africa's safest and cleanest countries.

Known as the "Land of a Thousand Hills", Rwanda is a small country of great diversity and natural beauty. Gorilla trekking in the forests of Rwanda's Volcanoes National Park is one of the world's greatest wildlife adventures.

The dominant "silverback" is leader and protector of a gorilla family (Copyright © James Weis).

Most visitors to Rwanda come to experience gorilla trekking in the last remaining montane rainforest in East/Central Africa. It was here that the late Dian Fossey brought the plight of the mountain gorilla to the world's attention during her 18-year study of gorilla behavior.

Unfortunately, just as Rwanda was emerging as one of Africa's top ecotourism destinations, the Rwandan Civil War began in 1990 and only culminated four years later, with the horrific 100-day genocide in 1994, which claimed roughly one-eighth of its population.

Rwanda's volcanoes are home to the mountain gorillas.

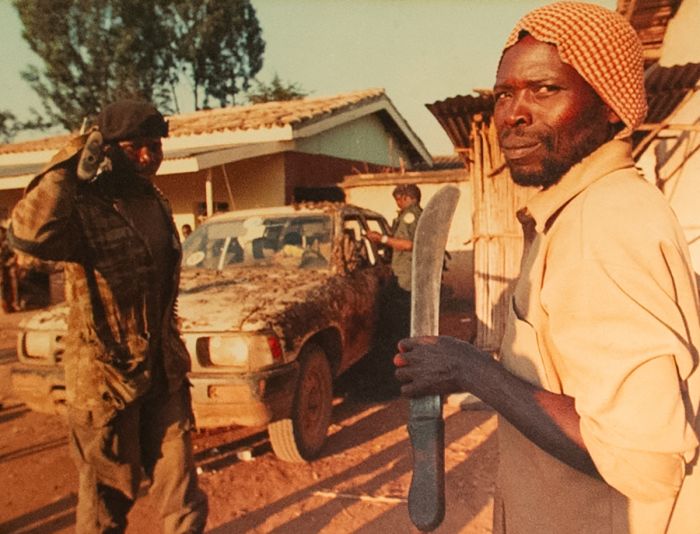

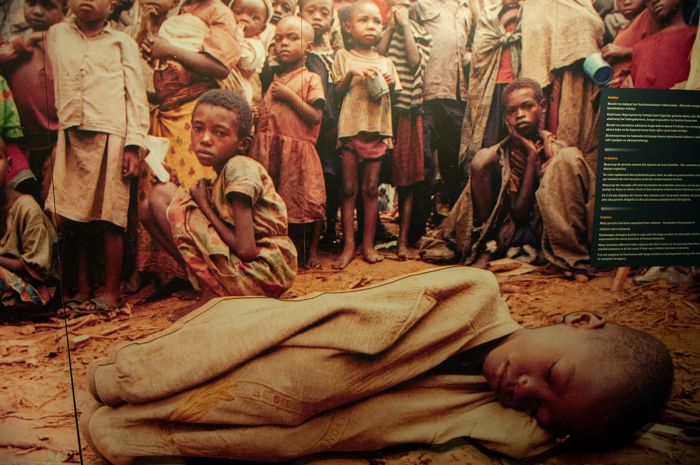

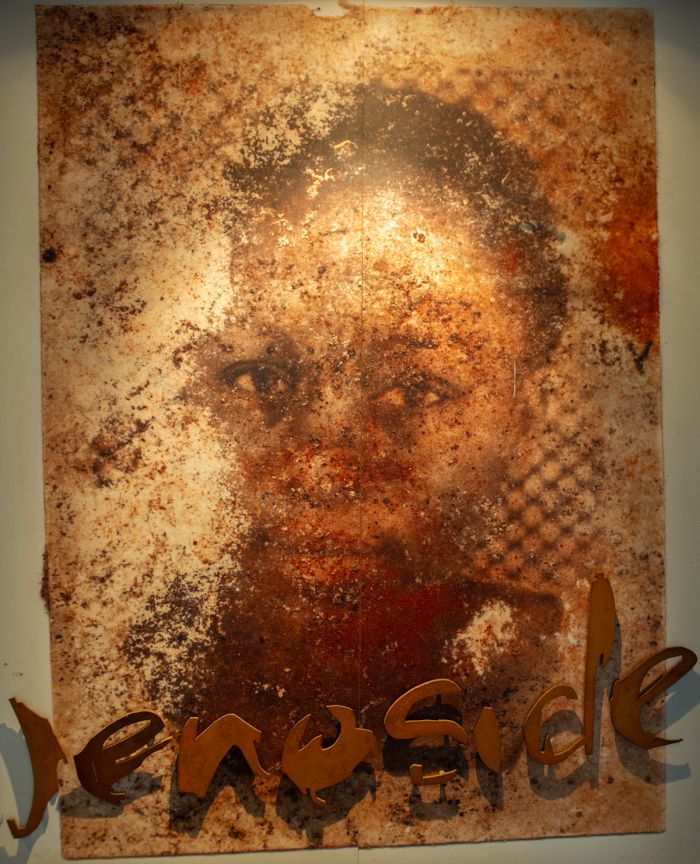

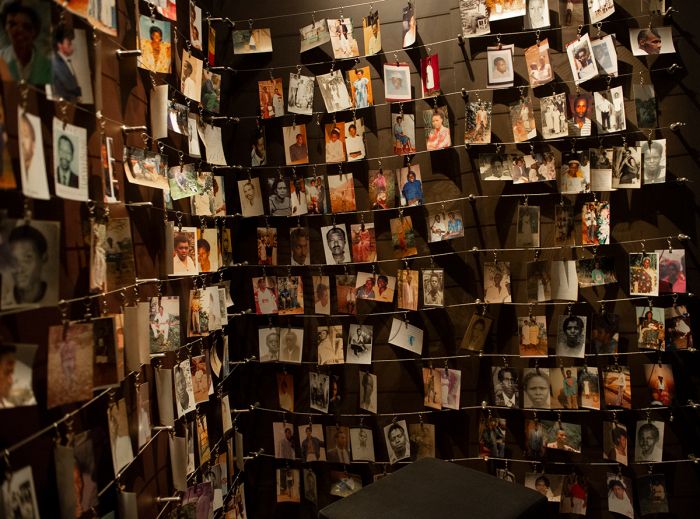

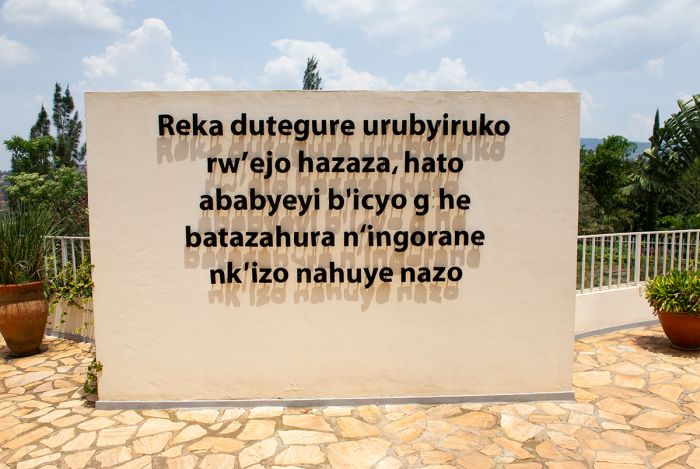

The genocide is memorialized in almost every city, town, and village in the country with Genocide Memorials. Rwandans believe that it should never be forgotten, so that it will never be repeated. The Genocide Museum in Kigali is a must-see for any traveller to Rwanda. It is a harrowing experience but should not be missed.

Today Rwanda is considered one of the safest, cleanest, and most politically stable countries on the continent. Its leaders are progressively looking to the future and have set a course of economic success and social enlightenment. Tourism, the majority of which is gorilla trekking, is now Rwanda's largest source of foreign revenue.

Exhibit in the Kigali Genocide Museum (Copyright © James Weis).

Joining a guided trek to spend an hour with one of the 'habituated' gorilla groups in Volcanoes National Park is certainly one of the world's greatest wildlife experiences. There are 10 gorilla groups that are visited daily by eight trekkers, and participation requires the purchase of a permit for that day. There are only about 1 000 mountain gorillas remaining in the wild.

Besides the lure of gorilla trekking, visitors can visit the enormous Nyungwe Forest, which is home to the country's only organized chimpanzee trekking and also offers spectacular canopy walks.

Gorilla trekking is an amazing wildlife adventure (Copyright © James Weis).

On the eastern border with Tanzania is Rwanda's only savanna-based safari destination, Akagera National Park. After the genocide, the park was victimized by poaching and resource depletion by returning refugees. In 2010, African Parks took over management of Akagera and has reintroduced lions, black rhinos and other species, transforming the park into a great safari destination.

Lions were recently re-introduced to Akagera National Park.

Rwanda Regions

Rwanda Volcanoes (incl. Volcanoes National Park, Gorilla Trekking)

Experience one of Africa's great adventures by joining a mountain gorilla trek in Rwanda's Volcanoes National Park. Only 1 000 of these critically endangered great apes remain in the wild. more

Read More...

Main: Flora, Geography, Important Areas, National Parks, Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, UNESCO Sites, Urban Areas, Wildlife

Detail: Akagera, Gishwati Forest, Kigali, Mukura Forest, Nyungwe Forest, Volcanoes

Admin: Travel Tips, Entry Requirements/Visas

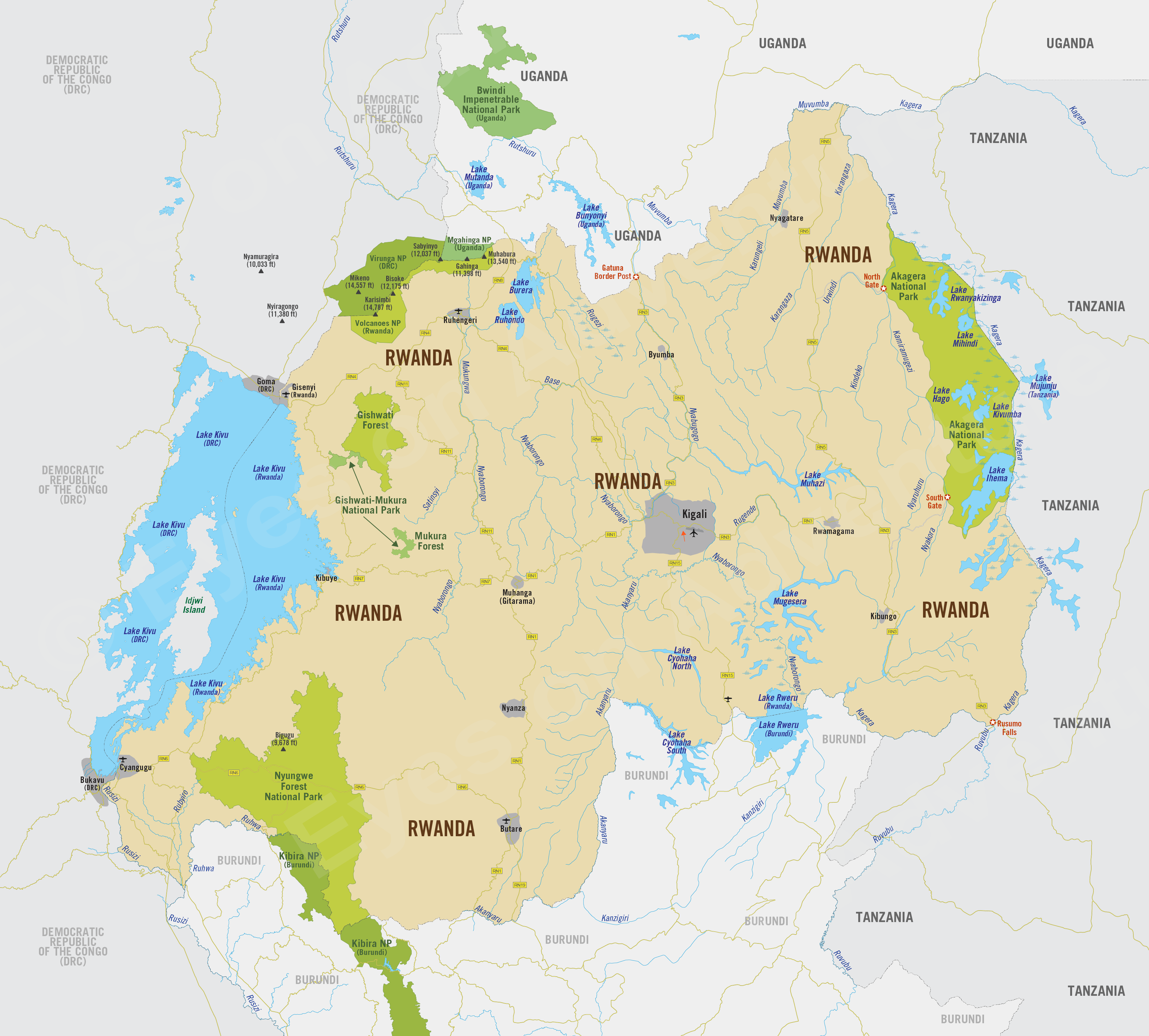

Geography

Rwanda is a small, landlocked country located in Central Africa and bordered by four countries: Tanzania to the east, Uganda to the north, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC, formerly Zaire) to the west, and Burundi to the south. Rwanda is the fourth smallest country on the African continent (after Gambia, Swaziland, and Djibouti). The country lies a few degrees south of the equator.

Known as the "Land of a Thousand Hills" ("Pays des Mille Collines" in French), the country is situated along the Albertine branch of Africa's East African Rift that runs from the Red Sea south to Mozambique. The Virunga Mountains are a group of eight volcanoes, two of which are active, that lie along Rwanda's western borders with the DRC and Uganda.

The Virunga Mountains on the western border of Rwanda.

Rwanda is located along a watershed between two of Africa's great rivers: the Congo and the Nile. Northwest Rwanda, which is characterized by high-elevation volcanic mountains, drains south into Lake Kivu, which then drains south into Lake Tanganyika via the Rusizi River and then into the Congo River.

The rest of the country, including the Nyungwe Forest in southwest Rwanda, all of central Rwanda, which sits on a plateau, and eastern Rwanda, which consists mainly of lowland savannas and swamps, drains to the west into the Kagera River. The Kagera flows north along the Tanzanian border, into Uganda, and then east into Lake Victoria, making it arguably the most remote source of the River Nile.

A tea plantation in western Rwanda.

Rwanda's highest point is along its western border atop the summit of Mount Karisimbi at 14 787 feet (4 507 meters). The interior of the country consists of rolling hills and valleys at elevations ranging between 5 000-8 000 feet (1 500-2 500 meters). The eastern edge of Rwanda is its lowest-lying land along the Kagera River, with an elevation of around 4 000 feet (1 200 meters).

Rwanda has numerous lakes, but Lake Kivu is by far the largest. Kivu sits along the floor of the Albertine Rift and the border between Rwanda and DRC runs through the lake. The lake is filled by rainfall in the volcanic highlands of the Virunga Mountains. Kivu is Africa's eighth largest lake and its surface sits at an altitude of 4 790 feet (1 460 meters) above sea level. Kivu's maximum depth is 1 558 feet (475 meters), making it one of the world's deepest lakes.

Lake Burera (Copyright © James Weis).

Flora

Before the arrival of humans, much of what is now Rwanda was covered in forests. During the period between 700 BC and 1500 AD, Bantu people began arriving and found the rich volcanic soils to be beneficial for farming. These early inhabitants cleared most of the forested land for use as agriculture.

The only large stand of true forest remaining in Rwanda is in Nyungwe Forest Nationa Park in the southwest, though there are still smaller remnants found around the country. The mid and upper elevations of the Virunga Mountains are covered in montane bamboo forests, Hagenia forest, and afro-alpine meadow. Volcanoes National Park protects the Virungas, as it is home to the country's top tourism draw, the mountain gorillas.

Giant lobelias and view of Mount Mikeno from upper Mount Karisimbi.

The lower elevations of the volcanoes are covered in terraced agriculture, where subsistence farmers grow potatoes, and pyrethrum. Large portions of land in the west are also used for short rotation eucalyptus tree woodlots and tea plantations.

The lower elevation land in eastern Rwanda is dominated by characteristic East African savanna grasslands and acacia tree scrubland.

Eucalyptus is grown for wood in western Rwanda (Copyright © James Weis).

Wildlife

As much as one-half of present-day Rwanda was once covered in rich forests, but rapid human population growth, particularly in the last 200 years, has fragmented much of the country's best wildlife habitat. Forests have been cleared for agriculture and poaching has worsened the situation.

There are essentially three protected wildlife areas in Rwanda: the Volcanoes National Park in the Virunga Mountains, which is a sanctuary for the endangered mountain gorillas; Nyungwe Forest, which is the best place in the country to see chimpanzees and various species of monkey; and Akagera National Park in the far east, which protects an East African savanna ecosystem and is home to lion, leopard, hippo, elephant, and numerous species of antelope.

A mountain gorilla holds her baby (Copyright © James Weis).

The mountain gorillas and the well organized gorilla trekking industry are by far the top wildlife tourism draw in Rwanda. Chimpanzee treks are offered in Nyungwe and traditional game-drive safaris are offered in Akagera, but both of these destinations see far lower tourist numbers than the very popular Volcanoes region.

All three of the national parks mentioned offer good birding, with a country list that tops 700 species.

A Masai giraffe in Akagera National Park.

Protected Areas

Rwanda is a small country and therefore does not have a long list of protected areas. All of its protected areas are designated as national parks.

National Parks

The country's four national parks are:

- Akagera National Park - an East-African savanna ecosystem with diverse wildlife and traditional game-drive safaris.

- Gishwati-Mukura National Park - Comprised of two separate, disconnected forests and home to chimpanzees and monkeys.

- Nyungwe Forest National Park - One of Africa's oldest rainforests and home to chimpanzees and monkeys.

- Volcanoes National Park - protects the Virunga Mountains and offers mountain gorilla trekking.

Trekkers walk thru cultivation en route to the gorillas (Copyright © James Weis).

Important Areas

Other areas of importance in Rwanda include Unesco World Heritage Sites and Ramsar Wetlands. Read more directly below.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations whose mission is to promote world peace and security through international cooperation in education, the arts, the sciences, and culture. The Convention concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage was signed in November 1972 and ratified by the 189 UN member "states parties".

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area which is geographically and historically identifiable and has special cultural or physical significance. To be selected as a World Heritage Site, a nominated site must meet specific criteria and be judged to contain "cultural or natural heritage of outstanding value to humanity". An inscribed site is categorized as cultural, natural, or mixed (cultural and natural). As of 2021, there were over 1 100 sites across 167 countries.

There are no UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Rwanda, but the country has submitted four proposed sites for inclusion as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) World Heritage Site. All four sites are related to the 1994 Genocide:

- Bisesero Genocide Memorial in Karongi District (Cultural).

- Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre in Gasabo District (Cultural).

- Murambi Memorial Centre in Nyamagabe District (Cultural).

- Nyamata Genocide Memorial in Bugesera District (Cultural).

Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. It was the first of the modern global nature conservation conventions, negotiated during the 1960s by countries and non-governmental organizations concerned about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for birds and other wildlife. The convention is named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, where the convention was signed in 1971.

Presently there are some 75 member States to the Ramsar Convention throughout the world which have designated over 2 300 wetland sites onto the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance.

Rwanda has 1 site designated as Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Sites) as follows.

- Rugezi-Burera-Ruhondo - Flooded valley along the Rugezi River at an altitude of 6 725 feet (2 050 meters). The river feeds Lakes Ruhondo and Burera. The Rugezi wetland is home to numerous endangered bird species and is an important headwater of the Kagera and Nile River systems. Agricultural activities threatened the wetland until the government halted the drainage and restored the wetland, for which it received international recognition including a Green Globe Award in 2010 (26 sq miles/67 sq kms)

Visiting the Genocide Memorial Centre in Kigali (Copyright © James Weis).

Urban Areas

Rwanda's only notable urban area is its capital and major port of entry. See details below.

- Kigali - Rwanda's only substantial city and its main economic hub. Nearly all international visitors fly in and out of the city.

Volcanoes National Park

Volcanoes National Park is Rwanda's top destination for adventure travelers. The park protects Rwanda's portion of the Virunga Mountains, which are comprised of eight volcanoes that are spreads out along the borders between Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

A mountain gorilla in Volcanoes National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

The big draw for tourists to the volcanoes is gorilla trekking to see the endangered mountain gorillas that live here. The experience is definitely one of the greatest wildlife experiences anywhere in the world. The other activity in Volcanoes NP is trekking to see the golden monkeys.

Read full details on the gorillas and Volcanoes National Park here.

The endangered golden monkey in Volcanoes NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Akagera National Park

Akagera is Rwanda's only protected East-African-type savanna ecosystem. Bounded on the west by the Kagera River (for which the park is named), which also forms the country's border with Tanzania, Akagera is rebounding from years of misuse and poaching in an effort to give Rwanda a true safari destination.

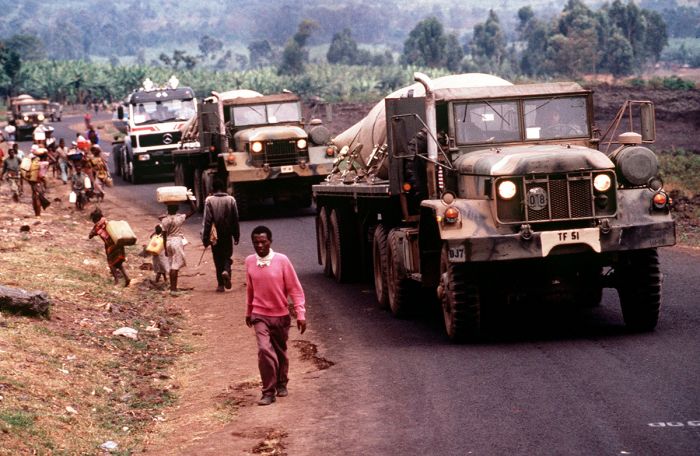

Originally proclaimed in 1934, Akagera was, until recently, a much larger reserve than it is today. In 1997, after the end of the genocide, considerable portions of western Akagera, as well as the adjacent Mutara Game Reserve to the north, were de-gazetted due to pressure on the area by thousands of returning refugees. The current reserve spans 433 square miles (1 122 sq kms).

Majestic bull elephant in Akagera National Park.

Akagera is relatively low-lying compared to the rest of Rwanda and is characterized by rolling grasslands, Acacia scrubland, dense woodlands, and an extensive wetland comprised of a complex of lakes and large areas of papyrus swamp.

Around the start of the 21st century, Akagera was on the verge of being forever lost, with genocide refugees inhabiting the north of the park and rampant poaching and overgrazing by cattle threatening its ecosystems. Fortunately, in 2010, African Parks, a non-profit conservation organization, assumed management of Akagera in partnership with the Rwandan Development Board (RDB), which is the government agency responsible for managing Rwanda’s national parks and protected areas.

Lions were recently re-introduced to Akagera.

Today, Akagera has made an astounding recovery under the new management, with restoration of lands and the reintroduction of two iconic species that had been wiped out by poaching.

In 2017, eighteen black rhinos were reintroduced after years of absence. Additional rhinos have since been added to the park to diversify the genetic population. In 2021, a group of white rhinos were also introduced to the park.

In 2015, lions were reintroduced and the big cats are now regularly seen on game drives. Akagera is now officially a Big Five destination.

Anti-poaching patrols have essentially eliminated the once-rampant poaching in the park and a predator-proof fence was erected in 2013 along the western border to reduce human-wildlife conflict in the western side of the park. Environmental education is a key program for ensuring that local children grow up with a respect and value for their country's wildlife.

Zebras are commonly seen in Akagera.

A new safari camp was recently built in the northern portion of the park, adding tourism presence to this more remote area and improving the park's future prospects.

In addition to once again offering all of Africa's Big Five animals, Akagera offers a high diversity of wildlife species, owing to its diverse range of habitats. Elephants and buffalos are seen regularly and leopards are present, especially in the woodlands. Herbivores include impala, defassa waterbuck, zebra, roan, Masai giraffe, bohor reedbuck, topi, eland, oribi, and more.

The elusive leopard seen on a game drive in Akagera.

Hippos and crocodiles are plentiful in the vast swamps along the eastern side of the park. The rare and shy sitatunga can also be seen, usually from a boat ride in the papyrus swamps. Birding in the park is spectacularly good, with over 400 species recorded. A day of birding can easily top 100 species and offers specials like the shoebill stork and papyrus gonolek.

Akagera is easily reached from Kigali via a two-hour drive and makes for a diverse addition to an itinerary that likely includes gorilla trekking in the mountains to the west.

Impalas and Akagera landscape.

Nyungwe Forest National Park

First declared as a protected forest reserve by the German Colonial authorities in 1933, Nyungwe protects the largest medium-altitude tract of rainforest remaining in Africa. It was once part of a far larger uninterrupted forest that covered the entire length of the Albertine Rift from Uganda in the north into Burundi in the south.

Iron Age people began clearing Rwanda's forests some 2 000 years ago to make space for agriculture, thus fragmenting Rwanda's forests and leaving only patches today.

Tea plantation in front of the Nyungwe Forest.

Covering an area of 393 square miles (1 019 sq kms) of dense rainforest, bamboo, wetlands, and grasslands, Nyungwe was proclaimed a national park in 2004. Nyungwe is situated along the watershed divide between two of Africa's great rivers: the Congo and the Nile.

Nyungwe's montane forests, which range from 5 250-9 678 feet (1 600-2 950 meters) in elevation, provide 70% of Rwanda's fresh water. A stream originating at the peak of Mount Bigugu (9 678 feet/2 950 m) is considered the most remote source of the Nile, the world's longest river.

A great blue turaco in Nyungwe National Park.

The Nyungwe Forest is one of the most diverse in Africa, owing to the fact that it was mostly unaffected by the drying up of lowland areas during the last ice age. For this reason, many species of animal and plant survived within the Albertine Rift forests. Nyungwe's diversity and high rate of endemism are also a function of the variation in elevations in the forest.

Surrounded by miles of terraced tea plantations and bisected by the tarred road from Butare to Cyangugu, Nyungwe's main attractions are its miles of hiking trails that wind through unspoiled forests. Nyungwe also offers chimpanzee trekking, numerous other species of primate, excellent birding, and a canopy walk.

A L'Hoest's monkey in the Nyungwe Forest.

Guided walks to see the park's semi-habituated chimps are a highlight, but any nature lover will delight in walking on any of the fifteen hiking trails that wind through the forest. More than 1 000 plant species are know to exist in the forest, including some 200 species of orchid and 250 plants that are Albertine Rift endemics. Over 300 species of birds have been recorded in Nyungwe, as well as some 120 species of butterfly.

Besides chimpanzees, there are 12 additional species of primate that can be seen in Nyungwe: L'Hoest's monkey, Ruwenzori colobus monkey, silver monkey, golden monkey, crowned monkey, Hamlyn's (owl-faced) monkey, red-tailed monkey, Dent's mona monkey, vervet monkey, blue monkey, olive baboon, grey-cheeked mangabey. The regionally endemic Ruwenzori colobus, a subspecies of the Angolan black-and-white colobus, is found in good numbers, with troops that exceed 300 individuals.

A Ruwenzori colobus monkey is a regionally endemic subspecies.

Nyungwe's suspension bridge and canopy walk towers above the ground and offers spectacular, if not dizzying, views of life at the top of the forest canopy. The walkway spans a total of 968 feet (295 meters), divided into three sections, with a maximum height of 230 feet (70 meters) above the forest floor. The canopy walk offers the best opportunity to view some of the forest's arboreal primates at eye level.

Nyungwe is seldom included on itineraries to Rwanda, mostly because the gorillas in the Virunga Mountains are by far the country's prime attraction and most visitors come solely for gorilla trekking. However, for those wishing to add diversity to their visit to Rwanda, Nyungwe is definitely worth a few days to explore.

Nyungwe's canopy walkway affords spectacular views of the treetops.

Gishwati & Mukura Forests

Rwanda's most recently created national park is Gishwati-Mukura, which was proclaimed in 2015. The park consists of two separate tracts of forest, the Gishwati and the Mukura. The two forests were once connected, but are now disparate due to human pressure for agriculture and cattle farming. As of 1930, the Gishwati portion covered some 110 square miles (283 sq kms), but it has since lost around 90% of its cover.

In 1989, the last remaining population of hunter-gatherer Twa people were forcibly removed from the Gishwati Forest and large portions of the forest were cleared in the early 1990s for eucalyptus plantations and dairy farming. In 1998-99, more forest was cleared to accommodate returning refugees from the genocide.

Gishwati Forest is home to various primates, including the golden monkey.

Unfortunately, beyond the sad loss of biodiversity, the deforestation has caused the drying up of streams that had previously provided water to communities living adjacent the forest. In 2008, terrible floods caused by the deforestation led to landslides that destroyed hundreds of homes and killed large numbers of people living around the reduced forest.

The national park consists of a small portion of the Gishwati Forest and all of the Mukura Forest and is currently undergoing an ambitious restoration program. The Gishwati Forest is home to small numbers of chimpanzees and several species monkey. Plans have been made to connect the separate forests to each other via a replanted corridor and hopefully then connect them to the Nyungwe Forest further south.

The Rwenzori turaco is one of Gishwati's beautiful birds.

Kigali

Originally founded in 1907 by Richard Kandt, the German explorer who discovered one of the sources of the Nile River in the Nyungwe Forest. Kandt explored the northwest of Germany's East African colony between 1897 and 1904 and was appointed as the first "Resident" of Rwanda.

Kandt chose Kigali as the location for the colony's administrative center due to its central location and its elevation on Nyarugenge Hill, which afforded good views and security. His house in Kigali is now the Kandt House Museum of Natural History.

Kigali's CBD skyline on Nyarugenge Hill.

Kigali remained a very small town throughout German rule. Belgium took control of Rwanda after World War I, but most of the colony's administration took place in Ruanda-Urundi's capital of Usumbura (now known as Bujumbura in Burundi).

Usumbura had a population of around 50 000 during the 1950s, while Kigali remained much smaller, with only 6 000 residents. When the Ruanda-Urundi colony was split into two independent countries in 1962, Kigali became the capital of Rwanda.

View of Kigali's outskirts and surrounding hills.

After independence, Kigali became Rwanda's capital and it grew quickly, sprawling in size and reaching a population of 240 000 by 1991, Today, the Kigali metro area has around 750 000 residents. In spite of the city's rapid growth, it is surprisingly free of litter and was proclaimed Africa's cleanest big city in 2008. The city is also quite safe by any big city standard.

Kigali's CBD is located on Nyarugenge Hill, which is located on the western side of Kigali. The CBD is a very built-up area near the location where Kandt built his house in 1907. Southwest of the CBD is the suburb of Nyamirambo, which was built by the Belgians as a living quarter for civil servants and Swahili traders. The Swahili traders were mainly muslims from the Indian Ocean, leading to Nyamirambo's becoming known as the "Muslim Quarter".

Traditional market in Kigali.

Most of the urban sprawl in Kigali is to the east of the CBD, with neighborhoods spanning onto the rolling hills and ridges in that direction. Kigali offers several very good hotels, including the Hôtel des Mille Collines, which became famous for its role in the genocide.

Most visitors to Rwanda pass through Kigali and we highly recommend every visitor make time to visit the Gisozi Genocide Memorial and Education Centre. The memorial is the final resting place for more than 250 000 genocide victims and it is open to the public. The self-guided tour (with headset) of the very well-done Education Centre is well worth the 90 minutes to experience its three permanent exhibitions. Visiting the Museum is a harrowing and emotional experience, but also very educational.

Nighttime view of Kigali's skyline.

Quick Facts & TRAVEL TIPS

- Rwanda is considered part of the Central Africa region. It has a tropical highland climate and although it is located close to the equator, its high elevations moderate its temperatures.

- Rwanda receives good rainfall with two "rainy" seasons: the long and more regular rains fall from March thru May and the short rains fall in October and November. Rain can fall at any time in the the mountainous western side of Rwanda.

- There are four official languages in Rwanda: Kinyarwanda, English, French, and Swahili. Kinyarwanda is a Bantu language and the first language of virtually everyone. French is a holdout from Belgian colonialism (1916-1962). English became the language of instruction in 2008.

- The national currency is the Rwandan Franc (RWF). US Dollars (old bills often not accepted) are widely accepted in the cities and hotels, often resulting in better rates than if using Rwandan Francs. UD Dollars are also preferred for gratuities, especially for gorilla trekking.

- Rwanda uses 230v electricity and types C and J plug adapters.

- Rwanda time is GMT+2 and it does not observe daylight savings time (DST); 7 hours ahead of New York (6 during DST).

- The population of Rwanda is around 13 million, with about 750 thousand in its largest metro area, Kigali. About 18% of the population is urban.

- Rwanda's land area covers 9 525 square miles (24 670 sq kms) with around 1 360 people per sq mile (525 people per sq km).

- All of Rwanda's indigenous people are of Bantu-speaking origin. Before the 1994 genocide, Hutus comprised 90%, followed by Tutsis (9%), and the Twa/Batwa (1%). Tutsis suffered at least 500 000 casualties in the genocide. Today, all Rwandans are officially considered the same ethnic group: Rwandan.

- Most whites, originally of European descent, left the country after independence in 1962. Very few whites, Asians, or foreign Africans are living in Rwanda.

- The majority of Rwandans are Christians, accounting for around 95% of the population. There is a small (2%) Muslim population.

Happy children seem to be everywhere these days in Rwanda (Copyright © James Weis).

ENTRY / VISA REQUIREMENTS

- Passport holders from USA/Canada/Australia/UK/EU can obtain a visa on arrival, from their local embassy, or online.

- Passport must be valid for six (6) months from the date of entry.

- Passport must have one (1) unused (blank) page labeled Visa.

- Note: Visa pages referred to above do not include pages reserved for Endorsements, Amendments or Observations.

- To save time at the airport, it is recommended to obtain a visa in advance.

- Multiple-entry visas must be obtained in advance.

- Single-entry visas are valid for thirty (30) days. Multiple-entry and East African Tourist visas are valid for ninety (90) days.

Note: entry/visa requirements are subject to change without notice, so please check with the official government pages shown below.

EAST AFRICAN TOURIST VISA

- Travelers who will visit Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda can apply for an East Africa Tourist Visa, which allows entry to all three countries on a single visa.

- A tourist using the East Africa Tourist Visa must start travel from the country that has issued the visa.

- Traveler must stay within only Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda to continue to use the visa; entry into a different country will terminate the validity of the visa.

- East Africa Tourist visas may be obtained online or on arrival at the first port or entry into Kenya, Rwanda or Uganda.

- To apply for the East African Tourist Visa online, use the consulate website for the FIRST COUNTRY you will visit.

- East African Tourist Visas are valid for ninety (90) days.

OFFICIAL GOVERNMENT PAGES

- US Department of State info: click here.

- Rwanda Consulate - USA: click here.

- Rwanda eVisa application: click here.

- Rwanda Home Affairs: click here.

- CDC information: click here.

Read More...

Main: Flora, Geography, Important Areas, National Parks, Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, UNESCO Sites, Urban Areas, Wildlife

Detail: Akagera, Gishwati Forest, Kigali, Mukura Forest, Nyungwe Forest, Volcanoes

Admin: Travel Tips, Entry Requirements/Visas

Read More...

Belgian Control, Civil War, Colonization, Coup d'état, Early History, Habyarimana Regime, German Control, Hutus, Independence, Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), Tutsis, Ubuhake, Post-War Rwanda

Genocide: Genocide, Genocide Aftermath, Genocide Justice, Habyarimana Assassination, Hutu Refugees, Kibeho Massacre, Lead Up to Genocide, Operation Turquoise

Early History

Although not dated with certainty, the first human habitation of present-day Rwanda is believed to have begun shortly after the end of the last Ice Age, during the late Stone Age roughly 10 000 years ago. These early inhabitants are known as the Twa (or Batwa), a Bantu-speaking tribe of forest hunter-gatherer pygmy people indigenous to Central Africa.

Note: The descendants of the early Twa are still found in populations living today in Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, and eastern DRC, but they have long been marginalized and number only an estimated 8 000 in total.

Archeological discoveries during the 1950s found evidence, including smelting furnaces, iron tools, and dimpled pottery, of early Iron Age (there was no Bronze Age in sub-Saharan Africa) settlements in present-day Rwanda and Burundi.

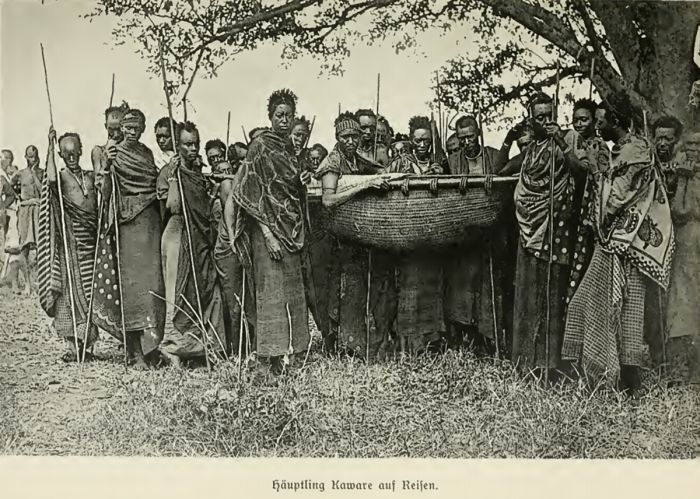

Tutsi Chief Kaware, circa 1900 (image: Wikimedia Commons).

Hutus and Tutsis (700 BC-1500 AD)

During an extended period between 700 BC and 1500 AD, a number of Bantu groups migrated south into present-day Rwanda and Burundi, finding the fertile soils beneficial for agriculture. These new Bantu groups cleared forested land for farming, thus displacing the forest-dwelling Twa people. The Twa lost much of their habitat and were forced to move west into the montane forests.

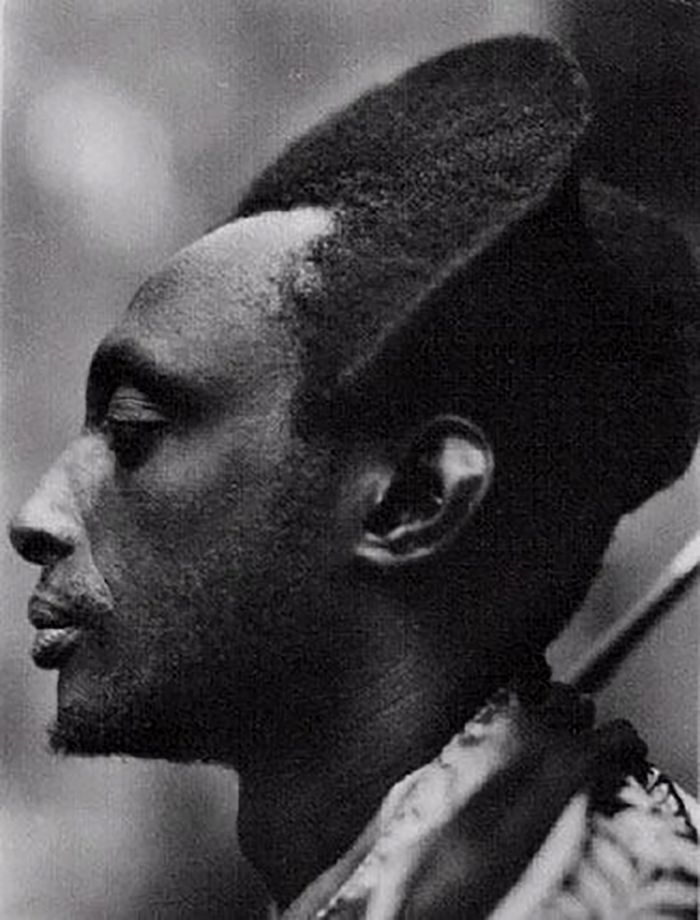

The early Bantu farming culture was later referred to as the Hutu people. Further Bantu expansion into the region included pastoralists, who later became known as the Tutsi people. Gradually, an ethnic/class division developed between the taller, lankier, and lighter-skinned, cattle-raising Tutsis and the shorter, sturdier, darker-skinned Hutu farmers developed.

A Tutsi herdsman with traditional hairstyle (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Throughout the period of Bantu expansion into present-day Rwanda, the development of a social structure was formed, whereby people were assigned to clans, which coalesced into kingdoms. Kingdoms were ruled by a king, called a "mwami". The dominant kingdom was ruled by the Tutsi-based Nyiginya clan, and their first mwami was named Abanyiginya, who was regarded as a divine being "descended from the heavens".

Sometime in the late 10th or early 11th century, Gihanga, who was the great-great-grandson of Abanyiginya, established the Kingdom of Rwanda. According to oral legend, Gihanga was succeeded by his son Gahima I (also known as Kanyarwanda I), who is reputed to have unified all clans into three main clans, the Gatwa, Gahutu and Gatutsi, which essentially divided people as Twa, Hutu and Tutsi, respectively.

Kigeli IV Rwabugiri, Mwami from 1853-1895 (image: Wikimedia Commons).

Ubuhake (1500-1880)

Beginning around 1500, a social order called "Ubuhake" began to develop, which essentially gave a superior social position to the cattle-owning Tutsis, while the Hutu farmers assumed a lower position in society. At the very bottom were the Twa.

Ubuhake gradually evolved into a class system whereby land, cattle and power were consolidated into the minority Tutsi group, while the Hutus basically became indentured servants to the Tutsis. The Tutsi masters granted their Hutu servants protection and the use of their land and cattle in exchange for farm produce and service. While Ubuhake agreements were voluntary and revokable between the master and servant, a Hutu peasant could not easily survive without a Tutsi patron.

Twa (Batwa) women (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Colonization (1884-1962)

By the late 1800s, much of Southern and East Africa had been exploited by Arab and European traders to one degree or another, but for 150 years or more, Rwanda had remained largely unexplored and unaffected by these traders. Due to Rwanda's isolationist policies, it did not engage in trade beyond its borders and foreigners were met with aggressive resistance. The slave and ivory trade peaked in the mid-1800s, but Rwanda is one of the few countries on the continent that was never directly affected by slave traders.

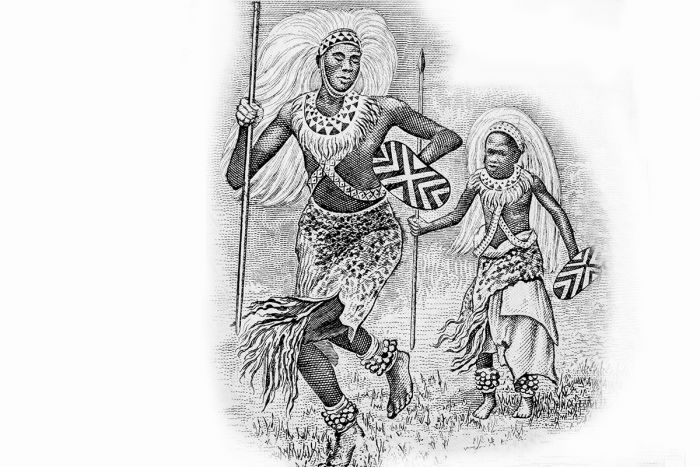

Tutsi warriors.

German Control (1898-1916)

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, organized by Otto von Bismark, the Chancellor of Germany, formalized the initial mapping of Africa into European colonies. Germany was allocated land that includes present-day Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi under the name German East Africa.

While the initial borders of most present-day African countries were established via colonization, the kingdoms of Rwanda and Burundi had existed for centuries and already had well-established borders. Rwanda was now unknowingly part of Germany's African colony, even though no European had ever set foot there.

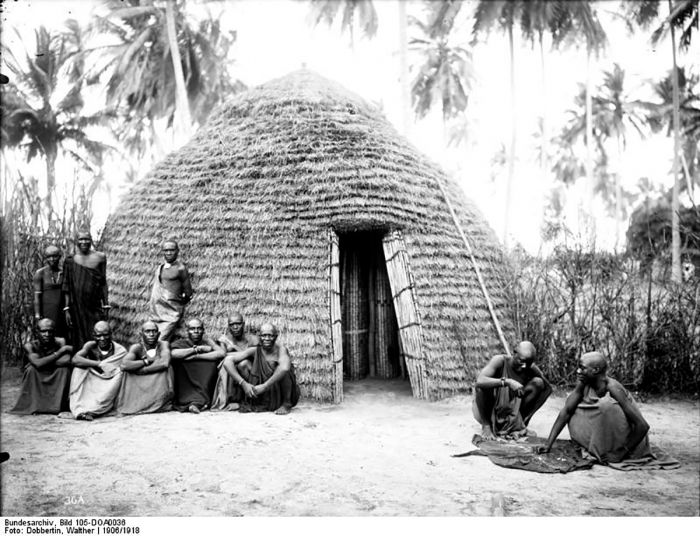

Native people living in German East Africa (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

The first non-African to officially set foot in Rwanda was Oscar Baumann, an Austrian cartographer, who entered Rwanda in 1892 via Burundi. Bauman only managed to spend a few days in the far south of the country before being forced to leave.

On 21 December 1893, a German expedition led by Gustav Adolf Graf von Götzen and accompanied by 620 soldiers, set out from Pangani, on Tanzania's Indian Ocean coast, to explore Germany's new colonies. After crossing west through northern Tanzania's Maasai lands, the expedition entered Rwanda from the southeast at Rusumo Falls on 03 May 1894.

Von Götzen's team crossed west through Rwanda, stopping to visit the mwami, King Kigeli IV Rwabugiri at his palace in Nyanza, and then continued to the shores of Lake Kivu. The mwami was surprised to hear that his kingdom had supposedly been part of a foreign colony for the previous nine years. Rwanda and Burundi were officially absorbed into German East Africa in 1898 under the name Ruanda-Urundi.

Gustav Adolf von Götzen (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

During the late 1890s, the Germans became aware that its new colony was administratively very organized and they decided to leave the existing chiefdom structures intact. In the first decade of the 1900s, the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches established numerous missions, schools, and farms in Ruanda-Urundi.

Germany also observed and perpetuated the existing social class system that separated the population into Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa. To this end, in 1907, Germany created a school for the children of the colony's elite families called the "School for the Sons of Chiefs" in Nyanza.

In 1911, Germany assisted the existing Tutsi monarchy in subjugating independent Hutu chiefdoms in the far north of Rwanda that had heretofore resisted Tutsi domination. The proudly independent northern Hutus fiercely resisted before they were defeated and brought under control of the mwami. The northern Hutu chiefdom's defeat served to deepen regional Hutu resentment towards the Tutsi.

Warundi archers in the Kingdom of Urundi (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Belgian Control (1916-1962)

In 1916, as part of the Allied East African Campaign during World War I, Belgium invaded Ruanda-Urundi and occupied the German colony for the remainder of the war. After the war, the Treaty of Versailles divided Germany's colonial empire among the Allied nations and a League of Nations mandate officially awarded Ruanda-Urundi to Belgium on 20 July 1922.

In addition to Ruanda-Urundi, Belgium had control of the massive Congo Free State, which existed as a corporate state from 1885-1908, allowing European countries access to the Congo River as a supply line to the Atlantic Ocean. In 1908, Belgium annexed the Congo as a Belgian colony.

From the beginning, the Belgians began implementing changes in several areas in an effort to improve the country's profitability. Rwanda, like most areas in Africa, was subject to severe periodic droughts resulting in terrible famines. Improvements to the colony's agricultural output was a key initial focus designed to safeguard the country against future famines.

A Belgian military officer and his family with King Yuhi V Musinga in 1919 (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Beginning in 1924, the Belgians made the cultivation of food crops compulsory for all rural land owners. In order to improve food production for subsistence farmers, the Belgians introduced foreign food species, including cassava, maize, manioc, sweet potato, and Irish potato. Food storage facilities were built, as well as processing plants. They also improved food distribution by building new roads and created food co-operatives and markets to help small farmers sell their product.

The Belgians also hoped to make the colony a profitable exporter and to that end, they introduced coffee and used a system of forced labor called "uburetwa" (similar to corvée), which required Hutu peasants to dedicate a certain portion of their fields to coffee. The Hutu farmers were not paid for their coffee crop, nor were they compensated for their labor.

This system of forced labor, which had existed in Rwanda since the 1850s under mwami Rwabugiri, was widely condemned by the international community and was of course unpopular in Rwanda. One result was a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Rwandans to the British protectorate of Uganda, which did not have these policies.

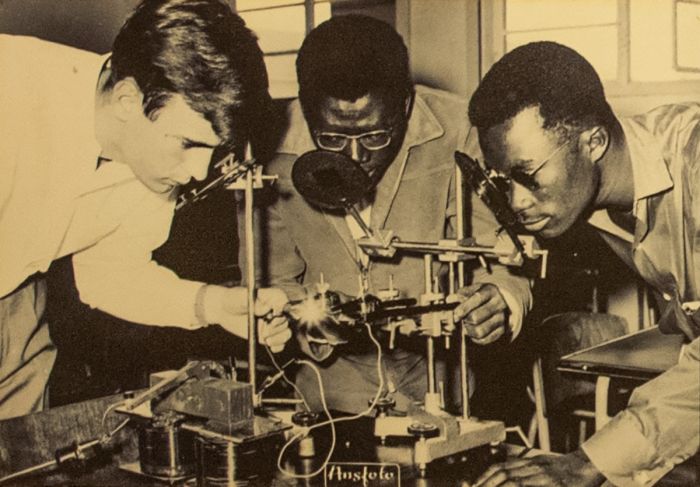

In addition to the agricultural changes, some positive and some not so much, the Belgians made significant improvements to Rwanda's infrastructure by building schools, roads, and hospitals, which gave employment to large numbers of Rwandans.

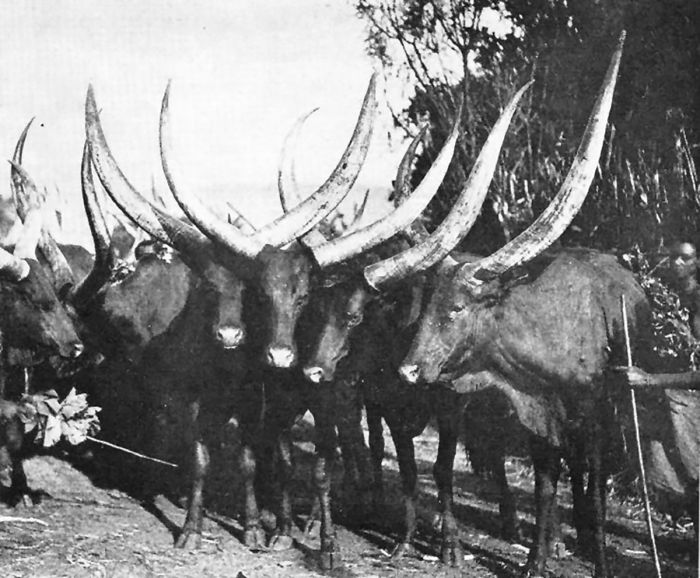

Prime Ruandan cattle in colonial times (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Like the Germans, the Belgians perpetuated the ethnic divide between the Tutsis and Hutus and supported the existing Tutsi-controlled power structure for administration of the colony. They also introduced their own Belgian administrators at every level of the government, which did not sit well with Mwami Yuhi V Musinga, who was the ruler at the time of Belgian accession. Due to the mwami's hostile stance towards colonization, the Belgians forced Mwami Musinga to abdicate his throne in 1931, granting power to his son, Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa, who was more Westernized and amenable towards the Belgian rule.

The eugenics movement in Europe led the Belgians to investigate the differences between the Tutsis and the Hutus, who appeared to them to be physically separate peoples. During the 1920s, Belgian scientists were brought in to study the perceived differences between Tutsis and Hutus. They found that Tutsi skull sizes were larger, leading them to conclude that Tutsi brains were larger. Furthermore, the Tutsis generally exhibited much lighter skin tones, leading the Belgians to assume that they had Caucasian ancestry and that they were therefore superior to the darker-skinned Hutus.

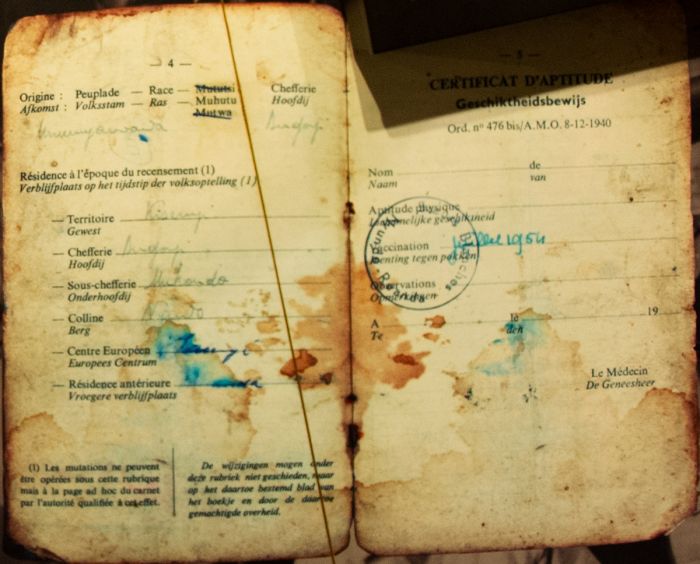

The result of the studies was that in the early 1930s, the Belgians undertook a census of Rwanda's indigenous population to determine every person's racial identity. In 1935, all Rwandans were issued racial identification cards, which legally defined them as either Tutsi, Hutu or Twa. If a person's physical qualities were blurred such that it was not immediately apparent that they were Tutsi or Hutu, the Belgians allowed that anyone of reasonable wealth or owning ten or more cattle would be classified as a member of the Tutsi class.

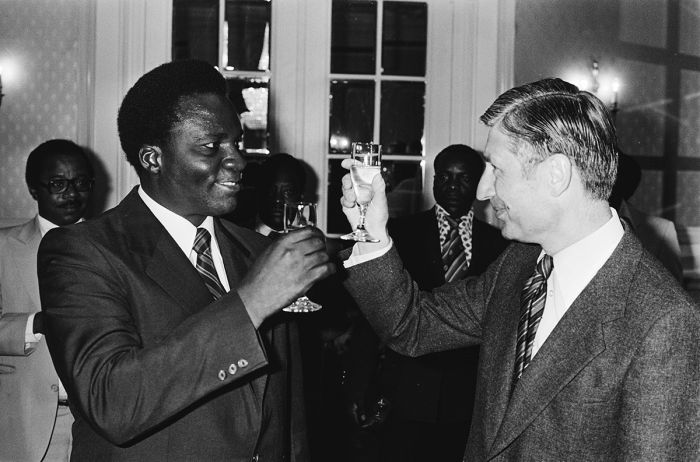

Belgium's King Baudouin welcomed by Mutara III Rudahigwa (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

After the legal separation of racial classes, the Belgians assigned most positions of political power to the minority Tutsis, who had begun perpetuating the myth of their racial superiority and exploiting their power over the Hutu majority. The Roman Catholic Church, which provided most of the country's education at its schools, also reinforced the Tutsi/Hutu racial classes and developed separate educational systems for each.

Following World War II, in 1945, Ruanda-Urundi became a United Nations Trust Territory with Belgium as the administrative authority. Trust Territories effectively replaced League of Nations mandates, with the goal being to transition all such territories towards eventual independence.

Throughout the 1950s, the Belgians instituted various reforms in an attempt to give more equality to the majority Hutu class, including more Hutu inclusion in Catholic schools, abolishment of the forced labor system, and land/cattle redistribution. The reforms were unsurprisingly resisted by the ruling Tutsi class and contributed to ethnic tensions between the two classes.

Catholic priests from Belgium having lunch near Kigali (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Independence (1957-1963)

In June 1957, Grégoire Kayibanda, an ethnic Hutu intellectual, founded the "Hutu Social Movement", a political party seeking Hutu emancipation from oppression. The party was soon renamed as "Party of the Hutu Emancipation Movement" (PARMEHUTU). That same year, Kayibanda co-wrote the "Bahutu Manifesto", denouncing the ethnic exploitation of the Hutus by the Tutsis and calling for the liberation of Hutus.

In July 1959, Mwami Rudahigwa traveled to Usumbura (now Bujumbura) in Urundi for a meeting with Belgian colonial administrators. The next day, the mwami visited a hospital for a routine check-up and died suddenly under highly suspicious circumstances. No autopsy was performed and rumors circulated that the Tutsi mwami may have been assassinated by Hutus. Kigeli V Ndahindurwa, Rudahigwa's half-brother, succeeded him as the new (and last) mwami of Rwanda.

The death of the mwami led to small-scale violence in Ruanda, with fighting erupting between Tutsis and Hutus throughout the country. Organized gangs of Hutus took to the streets of towns and villages, burning, looting and killing Tutsis. Tutsi groups retaliated. In November 1959, a Tutsi group attempted to assassinate Kayibanda, but they failed.

Monsignor André Perraudin moved Catholic support towards the Hutus (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Following a brutal attack by Tutsi extremists on Dominique Mbonyumutwa in November 1959, one of the few Hutu sub-chiefs in the country, larger scale violence swept through the country. Tutsi deaths were estimated at 20 000 to 100 000, with many thousands more, including the mwami, fleeing to Uganda.

To quell the violence, a Belgian military officer named Guillaume "Guy" Logiest was given military command over the colony. Colonel Logiest and his commando troops brought an end to the violence. Logiest was openly sympathetic to the Hutu plight and began replacing Tutsi chiefs with Hutus. In a complete turnabout from a long history of Hutu subjugation, a UN special commission reported that there was now widespread racism and discrimination against the Tutsi minority being perpetuated by the Belgian colonial administration.

Tutsis were favored in terms of education (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

During the ethnic violence of 1959, an estimated 150 000 Tutsis fled to neighboring countries including Uganda, Congo, and Urundi, while those that remained were excluded from any political power in the increasingly Hutu-controlled state.

In 1960, the first democratic elections were held in Ruanda, with the PARMEHUTU party winning the majority of positions, but there was widespread suspicion that the elections had been manipulated. Grégoire Kayibanda was declared the new leader of the country by the newly elected Hutu government. However, the UN refused to recognize the results of the hastily held elections and demanded that new elections be held with UN supervision.

The follow-up, UN-supervised elections were held in September 1961. The elections were for parliamentary positions and included a referendum seeking to end the ruling monarchy. The Hutu-majority populace voted overwhelmingly in favor of the PARMEHUTU party and to replace the Kingdom with a Republic. Kayibanda was declared as acting prime minister and Mbonyumutwa as acting president in the new transitional government.

President Gregoire Kayibanda with President John Kennedy 1962 (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

After the 1961 elections, the violence continued, with thousands of Tutsi homes burned, hundreds killed, and many thousands fleeing the country as refugees. Displaced Tutsis formed guerrilla groups and staged attacks from neighboring countries. Rwandan Hutu-based troops responded and thousands were killed on both sides in the fighting.

In July 1962, Belgium, with UN oversight, granted full independence to Ruanda-Urundi, creating the separate countries of Rwanda and Burundi. Rwanda was governed by the PARMEHUTU party, which had full control of the country's government. Rwanda was now a Hutu-dominated, one-party state with Kayibanda as president.

In 1963, further Tutsi guerrilla attacks launched from Burundi led to anti-Tutsi backlashes by the Hutu government, with their military killing 15 000 people in Rwanda. Tensions between Rwanda and Burundi escalated.

Children display placards of the new independent Rwanda flag (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Hutu Control (1964-1989)

In 1964, Kayibanda's regime banned the two Tutsi-based political parties (UNAR and RADER) and executed Tutsi members of those parties. Many thousands of Tutsis fled to neighboring countries as refugees. The Catholic Church was instrumental in providing early assistance to the Hutus and it maintained close links with the ruling PARMEHUTU government.

Rather than seeking a policy of integration and reconciliation, the Hutu government sought to reinforce its supremacy and it pursued a strict policy of restriction against the Tutsis. Quotas were introduced against the Tutsis, who comprised 9% of the country's population, limiting Tutsis to no more than 9% of school and university positions, no more than 9% of governmental positions, and no more than 9% of total jobs in the workforce.

In 1965, national elections were held and Kayibanda, who now ran unopposed, was re-elected as president. The PARMEHUTU party won all 47 National Assembly seats. Kayibanda's cousin, Juvénal Habyarimana was appointed as Minister of the National Guard and Police with the rank of Major General. Four years later, in 1969, Kayibanda was again re-elected and PARMEHUTU was renamed as the Republican Democratic Movement (Mouvement Démocratique Republicain-MDR).

Over the next several years, Kayibanda's regime became increasingly dictatorial and was known to be extremely corrupt. The government's Tutsi-cleansing had become so bad that even those among his close Hutu followers were becoming concerned.

Grégoire Kayibanda, the first elected President of Rwanda (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Coup d'état (1973)

National elections were again scheduled to be held in September 1973 and leading up to the elections, Kayibanda sought to secure his ongoing rule by amending the duration of the presidential from four to five years and eliminating the existing presidential age limit of 60 years.

Meanwhile, the longstanding North-South regionalist Hutu rivalry was becoming more intense under the lengthy Kayibanda presidency. Discontent was rife among northern Hutu politicians due to Kayibanda's continued practice of appointing Hutus from his native prefecture in the south to positions of power, while mostly dismissing northern Hutus.

On 05 July 1973, two months before the scheduled national elections, Juvénal Habyarimana seized control of the country in a military coup d'état, successfully ousting Kayibanda's regime. Habyarimana was born in Gisenyi, in the north of the country, and it is thought that the coup was due to pressure from his northern Hutu supporters over the regional tensions in the North-South Hutu power struggle.

The coup was initially reported to have been bloodless, but it was later disclosed that 55 supporters of the Kayibanda regime had been executed. Kayibanda and his wife were placed under house arrest, where they were reportedly starved to death.

Juvénal Habyarimana seized control of the country in 1973 (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Habyarimana Regime (1973-1994)

In 1975, President Habyarimana created a new political party called the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (Mouvement Révolutionaire National pour le Développement - MRND), banning the Southern-Hutu led PARMEHUTU party and establishing a totalitarian state run by Northern Hutus. A 1978 referendum was approved which effectively made the country a one-party state and every citizen a member of the MRND.

Presidential elections were held in 1978, with Habyarimana as the sole candidate. He received 99% of the vote. Habyarimana was re-elected again in 1983 and 1988 (running each time as the sole candidate), and although this was a period of relative stability in terms of ethnic tensions, the Habyarimana regime proved to be little better than its predecessor in terms of corruption, dictatorial control, and discrimination against the minority Tutsis.

That said, the country's Hutu versus Tutsi conflict was somewhat replaced by continued tensions between Northern and Southern Hutus, with the Northern Hutus now in power and the Southern Hutus growing increasingly bitter and resentful.

Juvénal Habyarimana and Dutch prime minister Dries van Agt in 1980 (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Kagame, Rwigyema & RPF (1981-1990)

During the 1960s-1970s, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis had been forced to flee the country, becoming refugees in the neighboring countries of Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and Zaire (present-day DRC). Many of the displaced Tutsis were, of course, resentful of having lost their homes and longed to return to Rwanda.

In 1979, Uganda's despotic President, Idi Amin Dada Oumee, was overthrown by the Tanzanian military with aid provided by Ugandan refugees. President Amin escaped into exile and was succeeded by Milton Obote. Obote had himself been overthrown as president by Idi Amin in 1971, but was now returned to power and the presidency.

Following the overthrow of Amin, a group of Tutsi intelligentsia refugees living in Uganda formed a political refugee organization called the Rwandese Alliance for National Unity (RANU), to discuss a possible return to Rwanda.

Like Amin, Obote's regime was extremely oppressive and in 1981, Yoweri Museveni, a Ugandan politician who was involved in toppling Amin's regime, began a guerrilla war against the Obote regime. In 1981, Museveni formed the rebel National Resistance Army (NRA) and among his small group of founding soldiers were two Rwandan Tutsi refugees, Paul Kagame and Fred Rwigyema, both of whom had fled Rwanda with their parents as young children in the early 1960s amid the Hutu takeover and ensuing violence against the Tutsis. The NRA's goal was to overthrow the Obote government.

Thousands of Tutsis fled Rwanda in the 1960s-1970s (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Obote's regime was openly hostile to Rwandan refugees living in Uganda and Kagame and Rwigyema joined the NRA primarily to improve conditions for Rwandan refugees persecuted by Obote. The two Rwandans also had a longer-term goal of returning to Rwanda with other Tutsi refugees. Both soldiers received military training, with Kagame specializing in intelligence gathering and rising quickly in the ranks.

The NRA, with Kagame and Rwigyema, fought against the Ugandan army for the next five years (called the Ugandan Bush War) and in 1986, captured the capital of Kampala with a force of 14 000 soldiers, of which around one-qaurter were Rwandan Tutsi refugees. A new government was formed with Museveni installed as president and Kagame and Rwigyema as senior officers in the new Ugandan army.

Rwigyema was appointed Deputy Minister of Defense and Deputy Army Commander-in-Chief, second only to Museveni in the military chain of command for the nation. Kagame was appointed acting Chief of Military Intelligence. Kagame and Rwigyema began building a secret network of Rwandan Tutsi refugees within the army's ranks, intended to be the core group for a future attack on Rwanda.

In 1987, RANU renamed itself as the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF). The RPF was comprised largely of Rwandan refugee veterans of the Ugandan Bush War and was becoming much more militaristic than the original RANU.

Prime Minister Milton Obote with President Kennedy in 1962 (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Rwandan Civil War (1990-94)

RPF Invasion (1990)

On 01 October 1990, the RPF, led by Major-General Fred Rwigyema, invaded northeast Rwanda with a force of 4 000 soldiers. Paul Kagame was not present for this raid, as he was in the USA receiving military training at Fort Leavenworth's Army Command and General Staff College in Kansas.

Rwigyema led the invasion, but he was killed during the second day of the action, taking a bullet to the head. The circumstances surrounding his death are not known with certainty. The official account is that he was hit by a stray bullet, while another version says Rwigyema was killed by his sub-commander Peter Bayingana, following an argument over tactics.

Fighting continued without Rwigyema, but the RPF was repelled by a combined force consisting of the Rwandan Army and troops from France, Belgium, and Zaire (Congo). By the end of October, the RPF had been pushed back all the way to the Ugandan border.

The RPF moved its base into the Virunga Mountains of Rwanda.

The Habyarimana government used the attack by the RPF as a pretext for the arbitrary arrest of some 8 000 Tutsi political opponents. Radio Rwanda also began airing propaganda to incite ethnic hatred towards Tutsis, which led to more violence.

Kagame returned to Africa and took command of the RPF forces, which had lost roughly half of their troops. Kagame moved the RPF soldiers west along the Ugandan border and into the Virunga Mountains of Rwanda, where the high altitude and rugged terrain offered them protection from attacks.

Kagame spent the next two months reorganizing the RPF, fundraising, and recruiting more soldiers. Recruits were sourced from the thousands of displaced Tutsis in Uganda, Tutsis remaining in Rwanda, and even they even managed to recruit some high-ranking Hutus that had fallen out with the Habyarimana government. Kagame maintained extremely tight discipline among the RPF troops, forbidding them to steal or harass civilians, which he hoped would give the RPF a good reputation with Rwanda's local population.

Kagame forbade his troops from harassing locals (Copyright © James Weis).

Attack on Ruhengeri (1991)

Kagame reinitiated RPF attacks on 22 January 1991, when 700 RPF soldiers descended from the mountains and took the town of Ruhengeri, surprising the Rwandan Army, who were unable to defend the attack. Most of the civilian population fled the city.

A primary target in the town was the prison, which was the largest in Rwanda, and the RPF successfully liberated all its prisoners. The RPF was able to recruit some of the prisoners, including some high-profile former allies of President Habyarimana. The RPF withdrew from the town during the night, heading back to their hideout in the mountains.

The government sent troops to Ruhengeri the following day, but the RPF raided the town almost every night for the next several months, fighting against Rwandan troops. Over the following year, the RPF conducted quick-hit guerrilla raids along the northwest border areas, but never managed to make any serious progress inland.

By late 1991, the RPF had control of roughly 5% of the country, all of it along the northern border. One key capture by the RPF was the border crossing at Gatuna, which effectively cut of Rwanda's main import/export route to Mombasa, forcing all trade to flow through the much longer route to Dar es Salaam in the east.

The RPF took the town of Ruhengeri on 22 January 1992 (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Guerilla Warfare (1991-1992)

The renewed warfare led to a resurgence of violence against Tutsis remaining in Rwanda, much of it authorized by the Habyarimana regime. Over the first half of 1991, Hutu activists executed over 1 000 pastoralist Tutsis living in Kinigi, Ruhengeri, and Gisenyi.

The escalation in violence was further fueled by the formation of the Akazu, an informal organization of Northern Hutu extremists made up of friends and close relatives of President Habyarimana and his very influential wife, Kanziga Habyarimana. The Akazu was also called the "Zero Network", for their goal of achieving a Rwanda with zero Tutsis.

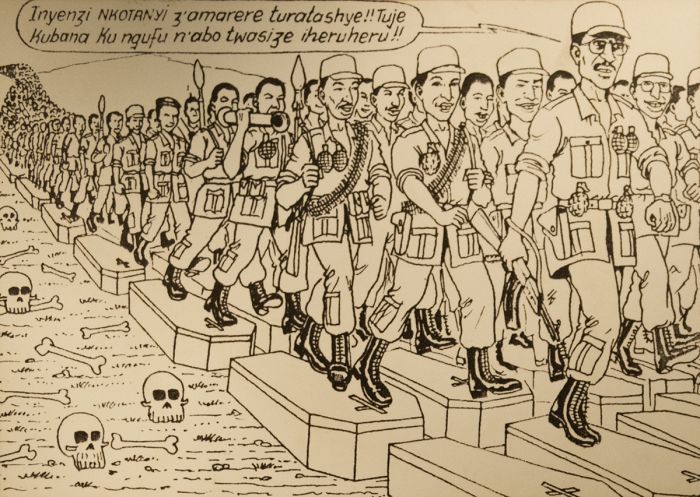

The Akazu engaged in a major propaganda campaign against the Tutsis, using radio broadcasting and written publications in an effort to persuade the Hutu population that Tutsis were a separate, non-Christian people that wished to restore the old feudal monarchy and enslave all Hutus.

Hutu propaganda shows Kagame leading the RPF over Hutu coffins. "Inyenzi", meaning 'cockroach' was used by Hutu radicals to dehumanize the Tutsis (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Peace Negotiations (1992)

By 1992, the RPF had expanded to a force of nearly 12 000 soldiers, was growing fast, and was conducting successful guerrilla raids along the northern border of the country. In January 1992, under intense global pressure, Habyarimana agreed to allow new political parties in the country. The president was also under pressure to end the conflict with the RPF, and to this end, agreed to enter negotiations with the RPF.

In July 1992, a ceasefire was announced while peace negotiations were held in Arusha, Tanzania. The negotiations were complex owing to the four very distinct groups involved, each having its own agenda:

- The hardline far-right Hutu extremists, which included the Akazu and hardline members of Habyarimana's MNRD party, who were officially organized in the newly formed Coalition for the Defence of the Republic (CDR);

- The official opposition, which excluded the CDR, and was much more moderate in its goal of a conciliatory democracy;

- The RPF, represented by Kagame himself, who was there only to keep the RPF from losing any international goodwill; and

- Habyarimana and his MRND party, which simply sought to hold on to its power. The president was wary of the radical Hutu faction that could compromise his position.

The negotiations made some progress during the latter half of 1992, despite continual disagreement between Habyarimana and the hardline members of his party that were interfering with the government's negotiating positions.

President Habyarimana with French President François Mitterrand in 1990 (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

RPF Offensive (1993)

In early 1993, MRND hardliners organized demonstrations across Rwanda, broadcast hateful propaganda about Tutsis on the radio, and mobilized their supporters in the army, which went on a killing spree that engulfed all of northwest Rwanda. The killing lasted six days, with many houses burned and hundreds of Tutsis killed.

Kagame responded by pulling out of the peace talks and resuming the war, ending the six-month cease-fire. The RPF offensive was also intended to increase its bargaining power in future negotiations by demonstrating superior military power in the field, which it had. The RPF advancement was met with weak resistance by the Rwandan Army, which was suffering from deteriorated morale due to a weakened national economy that left the government struggling to pay its soldiers regularly

The RPF moved steadily south, gaining ground with little or no opposition. They captured Ruhengeri on the first fay of fighting and continued inland, causing local Hutus to flee en masse, with most of them moving into refugee camps on the outskirts of Kigali. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of Hutu civilians were killed by the RPF during their offensive.

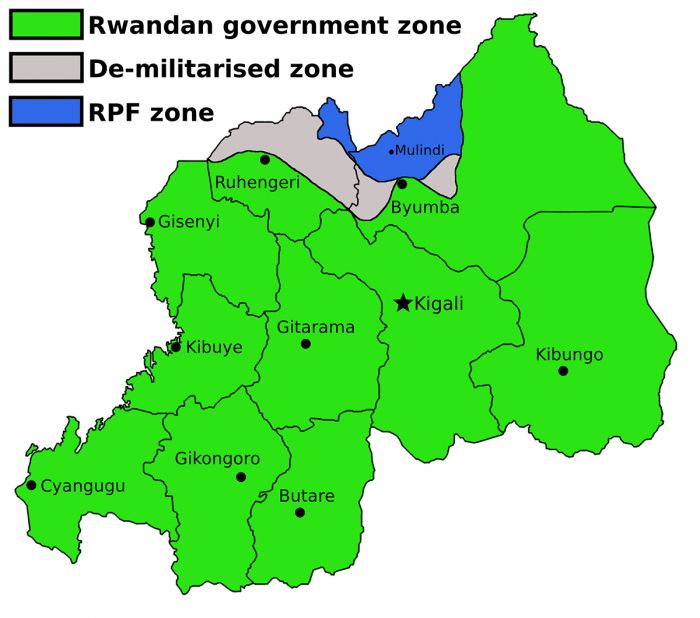

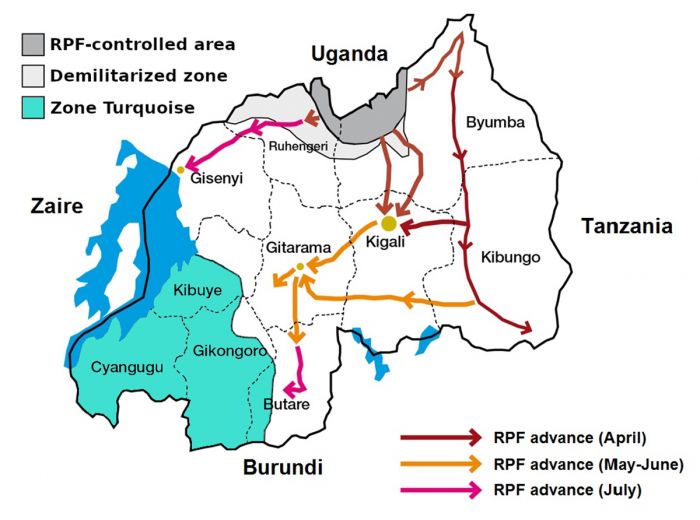

Fearing that the RPF could soon capture Kigali, Habyarimana requested urgent military assistance from France, which sent a battalion of 400 troops to Rwanda. The addition of the French troops halted the RPF advancement using intense shelling to thwart their movement. In February 1993, with their forces only 19 miles (30 kms) outside of Kigali, the RPF declared a cease-fire. More than one million civilians, mostly Hutus, had been forced from their homes during the RPF offensive.

The partition of Rwanda following the RPF offensive in February 1993 (image: Wikimedia Commons).

Resumed Peace Talks (1993)

Peace talks resumed in Kampala, Uganda, and Kagame agreed to pull back his forces to their pre-February territory, provided that there was a demilitarized buffer zone between the RPF forces and the Rwandese Government Forces (RGF). Habyarimana agreed to this significant concession, granting the Northern zone to the rebels and recognized the RPF's hold on that territory.

Over the following several months, hardline factions within the MRND and each of the opposition parties began to organize under a movement known as "Hutu Power", which transcended party politics. Except for the hardline CDR (Coalition for the Defence of the Republic), there was no party that was exclusively a part of the Hutu Power movement. The other parties were all split into moderate and "Power" factions, with members from each claiming leadership of their party. Even the ruling MRND had a Power faction, whose members opposed Habyarimana and any peace deal with the RPF.

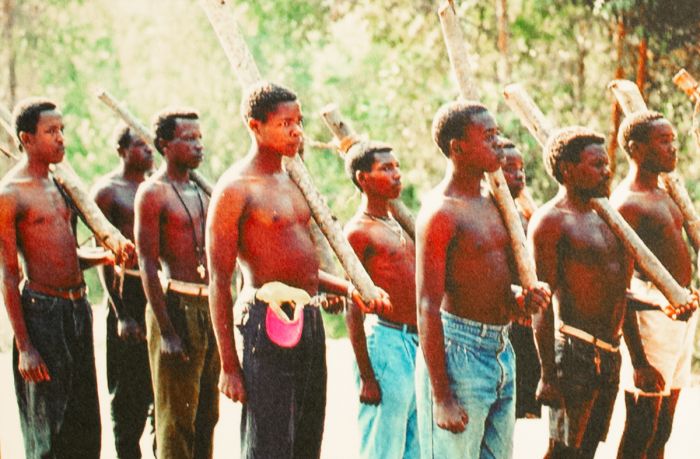

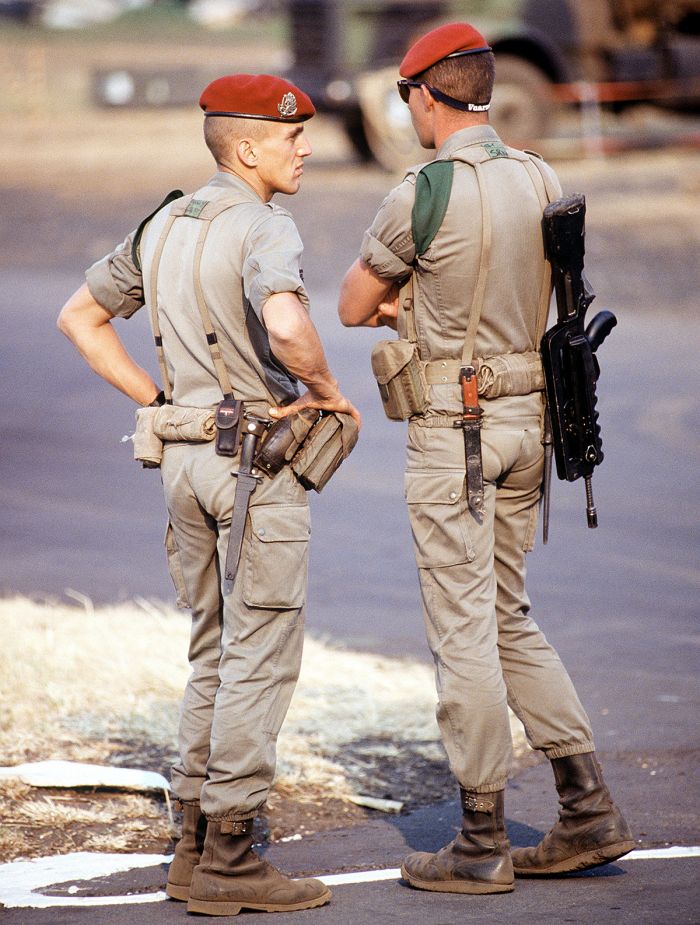

Several youth militia groups formed within the Power movement, including the MRND's Interahamwe ("those who stand together"), and the CDR's Impuzamugambi ("those who have the same goal"). These youth militia groups began terrorizing Tutsis, carrying out small-scale massacres across the country. The youth militia were being trained by the Rwandan Army, often with the assistance of French troops, who were unaware that their help was perpetuating mass killings.

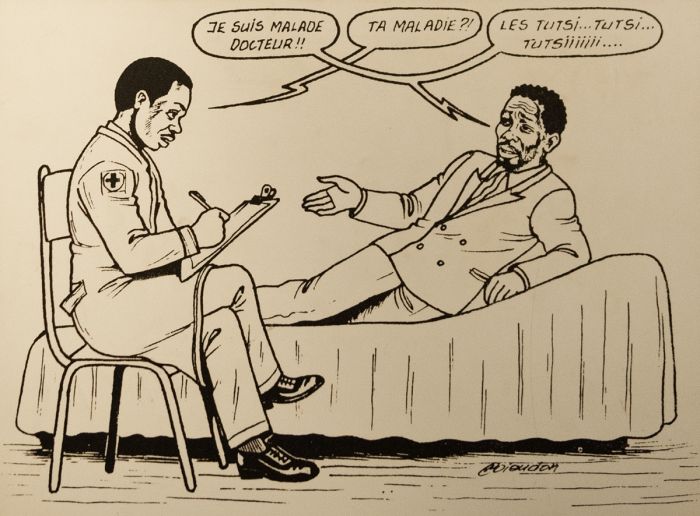

By June 1993, President Habyarimana realized that the Hutu Power movement was the greatest threat to his control, leading him to change his tactics and seek peace with the RPF. Negotiations resumed, but the RPF now had a superior position due to its successful February campaign and the Rwandan government eventually agreed to the RPF's demands for a 50% allocation of officer positions, plus 40% of the non-command troops in the Rwandan Army.

"I am sick doctor!! -What is your sickness?! -The Tutsis... Tutsi... Tutsiiiiii." The RPF are demonized as controlling the peace talks (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Arusha Agreement (1993)

On 04 August 1993, the parties came to an agreement (called the Arusha Accords or Arusha Agreement) on a Broad-Based Transitional Government (BBTG), which would include representation for the RPF. The agreement also committed Habyarimana to reforms, including Tutsi repatriation and resettlement, political power sharing among the five political parties, rule of law, and the above-mentioned integration of governmental and rebel armies.

The Agreement in fact favored the RPF, mostly due to the ongoing disagreements between hard-liners and more conciliatory moderates (Habyarimana) within the government. The Accords stripped numerous powers from the office of the president, transferring them to the BBTG, which was to rule the country until elections could be held. The BBTG was scheduled to be implemented within five weeks, overseen by a UN delegation.

Habyarimana, the mainstream moderate opposition, and the RPF all accepted the Agreement, but the CDR and hardline MRND officers were violently opposed. Hostilities escalated and the MRND national secretary announced that the party would not respect the Agreement, contradicting President Habyarimana and the party's negotiators in Arusha.

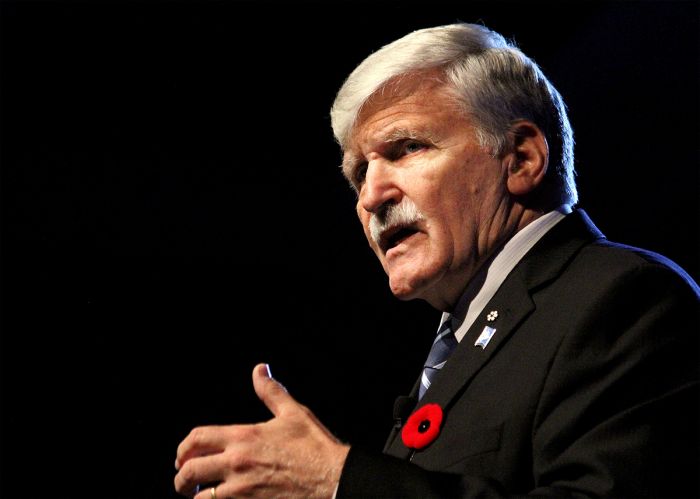

In October 1993, in order to assist in the implementation of the Arusha Agreement, the UN deployed a peacekeeping force called the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR). Its authorized force was 2 500 personnel (although it took months to reach this level) and was commanded by Canadian-born Major-General Roméo Dallaire.

Rwandan identity card showing race classification; in this case Hutu (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Lead Up the Genocide (1990-93)

As early as 1990, the Rwandan military had been arming Hutu civilians with machetes and other weapons, as well as training Hutu youths in combat tactics as "civil defense" against the RPF. The Interahamwe and Impuzamugambi youth groups, comprised largely of young men displaced from their homes in the north by the RPF, numbered some 50 000 by late 1993 and provided support to the national police and the Rwandan Army.

In March 1993, the Hutu Power movement had begun compiling a list of "traitors" that they planned on killing and it is quite likely that President Habyarimana was at the top of the list, with the CDR publicly accusing the him of treason. Hutu Power also founded their own radio station, Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) to spread their hardline anti-Tutsi propaganda. The RTLM was very popular among Hutu youths and it quickly gained a massive audience.

RTLM labeled the Tutsi as "inyenzi", meaning non-human pests or cockroaches, that should be exterminated. RTLM also accused the RPF of atrocities against the Tutsis and called for all Hutus to kill Tutsis. One well documented broadcast stated “Someone must make them disappear for good... to wipe them from human memory... to exterminate the Tutsi from the surface of the earth.” By the time the genocide began, Rwanda's Hutu populace had been fed months of racist radio propaganda that characterized all Tutsis as dangerous enemies that wished to eradicate all Hutus.

Habyarimana's MRND was responsible for establishing the Interahamwe youth militia (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

On 21 October 1993, Melchior Ndadaye, the newly-elected and first-ever Hutu-born President of Burindi, was killed in a military coup by Tutsi officers in the Burundian Army. The coup sparked a spree of massacres between Tutsis and Hutus in Burundi that eventually led to the Burundi Civil War. Ndadye's assassination also further fueled Hutu beliefs in Rwanda that Tutsis could never be trusted and were their enemies.

It was at this point that extremest Hutu groups in Rwanda began seriously discussing an idea first promulgated as early as 1992 and possibly as far back as 1990 termed the "final solution". In those days it was only a fringe point of view, but now it became the top of Hutu Power's agenda. The "final solution" was to kill every Tutsi in Rwanda. To this end, Hutu Power began arming the Interahamwe, Impuzamugambi, and other youth groups with large quantities of AK-47's (they had previously only possessed machetes and other crude hand-weapons) in anticipation of executing the "final solution".

During the latter months of 1993, tensions continued to escalate, with small-scale outbursts of violence.

Per the Arusha Agreement, Habyarimana was sworn in as interim President at the Parliament building, but before the swearing-in of his cabinet could begin, the president departed suddenly without explanation. He returned that afternoon with a list of new cabinet members from Hutu extremist parties, none of whom had been agreed upon in the Arusha Accords. The Chief Justice of Rwanda's Court refused to swear in the new ministers, which infuriated Habyarimana.

Habyarimana launched campaigns of persecution, fueling fear among his opponents (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Genocide Fax (1994)

On 11 January 1994, General Roméo Dallaire, the commander of the UN peacekeeping forces in Rwanda, sent a "most immediate cable" to UN Headquarters in New York that has since become known as the "genocide fax".

Dallaire's cable stated that an informant (later identified as Jean-Pierre Turatsinze), who was a top-level trainer in the MRND's Interahamwe youth militia, had disclosed that there was a Tutsi extermination plot being planned.

Important points made in Dallaire's communication included the following:

- Informant, who was born of a Tutsi mother, was in charge of Hutu demonstrations days earlier in Kigali that were designed to provoke the RPF into violence.

- High-ranking officials in the opposition parties were to be assassinated.

- UN troops were to be provoked into using force, upon which the peacekeepers were to be killed in order to force the UN to withdraw from Rwanda.

- Interahamwe has trained 1 700 soldiers in the Rwandese Government Forces (RGF) and stationed them in groups of 40 throughout Kigali.

- Since arrival of UNAMIR, Interahamwe has trained 300 additional soldiers in three-week sessions at RGF camps. Training focus was on discipline, weapons, explosives, close combat, and tactics.

- Until arrival of UNAMIR, the aim of Interahamwe was the protection of Kigali from RPF, but since the arrival of UN troops, informant has been ordered to register all Tutsis in Kigali. Informant suspects it is for their extermination. He stated that Interahamwe troops could easily kill 1 000 Kigali Tutsis in 20 minutes.

- Informant states that he supports opposition to RPF, but that he is against Tutsi extermination and killing of any innocent Rwandans. He believes that the president no longer has complete control over all elements of the MRND party.

- Informant is prepared to provide location of major weapons cache containing at least 135 automatic weapons. He has already distributed 110 guns, 35 with ammunition and can give details of their location. Weapon types are G3 and AK-47 and were provided by the RGF.

- Informant requests UN protection for himself and his family (wife, who is a Tutsi, and four children) in exchange for all information. He states that he would be expected to kill both his wife and his mother (both of whom are Tutsis).

- Dallaire requested permission to give informant protection and to evacuate him and his family out of Rwanda.

Roméo Dallaire, force commander of the UNAMIR peacekeeping force for Rwanda between 1993 and 1994 (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) in New York denied Dallaire's request to raid the arms caches and also denied his request to extend protection to his informant. It has been suggested that the UN feared taking action due to the loss of 20 UN peacekeepers in Somalia just two months earlier. New York ordered Dallaire to refrain from any “course of action that might lead to the use of force and unanticipated repercussions.”

Although the verity of the information provided by Jean-Pierre Turatsinze was never determined, the warnings in Dallaire's communication regarding the planned killings, sadly proved prescient. As an aside, after UNAMIR rebuffed his requests for protection, Turatsinze reportedly fled to Tanzania, where he joined the RPF and immediately traveled back to northern Rwanda to join the RPF army.

By March 1994, violence was escalating, especially in Kigali, with the Interahamwe executing scores of Tutsis, causing a sense of impending danger. Well-informed Tutsis and moderate Hutus were starting to evacuate their families from the city.

Violence was escalating, with hundreds of Tutsis being massacred; a preparation for what was to come (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Habyarimana Assassination (April 1994)

On 06 April 1994, President Habyarimana was in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania for a one-day regional summit for heads of state. Habyarimana traveled in the Presidential Aircraft, a Dassault Falcon 50 jet given to Rwanda by the French government, and joining him was Cyprien Ntaryamira, the Hutu president of Burundi (who had been appointed two months prior after the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye).

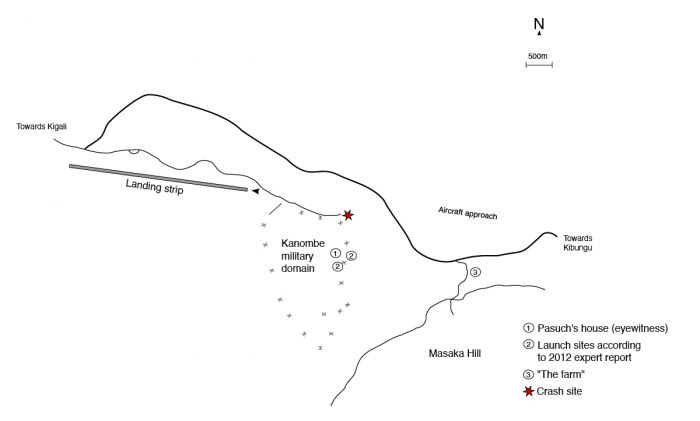

On the return flight back to Rwanda, as the plane approached Kigali Airport at around 8:30 pm, a surface-to-air missile struck one of the wings of the Dassault Falcon, followed by a second missile, which hit its tail. The plane erupted in flames in mid-air, before crashing into the garden of the Presidential Palace. In total, nine passengers and three crew were killed.

President Juvénal Habyarimana (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Who was Responsible?

The attack on the Presidential Aircraft was witnessed by numerous individuals, including a Belgian officer in the garden of a house in Kanombe, the district where the airport is located. All witnesses confirmed that two missiles hit the aircraft and that they both appeared to have come from the same location.

The location from which the missiles were fired is disputed. A Belgian inquiry concluded that the missiles had been fired from Masaka Hill, and that it would have been almost impossible for an RPF soldier to have reached Masaka Hill carrying missiles. A French investigation made public in January 2012 identified the Kanombe Military Barracks, which were controlled by governmental forces, including the Presidential Guard, as the likely source of the missile.

Responsibility for the attack has never been conclusively determined. Over the years since 1994, the subject has been investigated and disputed by various academics and parties, including the United Nations, which has never issued a definitive finding.

Map showing places relevant to the assassination of President Habyarimana (image: Wikimedia Commons).

Initial suspicion was placed upon "rogue Hutu elements of the military, possibly the elite Presidential Guard", who were thought to have carried out the attack in order to spur on the genocide. Both of the presumed missile launch locations would appear to suggest that the attacks could not have been carried out by the rebel RPF forces.

Differing reports in later years state that the attack was carried out by the RPF. In 1998, the French anti-terrorist magistrate Jean-Louis Bruguière opened an investigation into the downing of the aircraft on behalf of the families of the French aircraft crew. On the basis of hundreds of interviews, Bruguière concluded that the assassination had been carried out by the RPF on the orders of Paul Kagame. Various other investigations also concluded that the RPF was responsible.

In January 2010, the Rwandan government released the "Report of the Investigation into the Causes and Circumstances of and Responsibility for the Attack of 06/04/1994 Against The Falcon 50 Rwandan Presidential Aeroplane Registration Number 9XR-NN," known as the Mutsinzi Report. The multivolume report implicates proponents of Hutu Power in the attack.

A Dassault Falcon 50 similar to the one involved in the assassination (photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Kill Lists

Chaos ensued on the ground within minutes. A Crisis Committee was quickly formed, consisting of Major General Augustin Ndindiliyimana, Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, and a number of other senior army staff officers. Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, also known as Madame Agathe, was legally next in line to succeed as Head of State. General Dallaire met with the Committee and insisted that Uwilingiyimana be placed in charge, but the Committee refused to recognize her authority.

General Dallaire then sent a group of ten Belgian soldiers to Uwilingiyimana's home, with orders to transport the Prime Minister to Radio Rwanda, so she could address the nation. This plan failed, as the Presidential Guard had already overrun the radio station offices and would not permit her to speak on air.

On the morning on 07 April 1994, a group of Presidential Guard soldiers and a crowd of civilians overwhelmed the ten Belgians guarding the prime minister, forcing them to surrender their weapons. Uwilingiyimana and her husband were killed, but their children survived by hiding in the house and were later rescued by Senegalese UNAMIR officer Mbaye Diagne. The ten Belgian soldiers were taken to the Camp Kigali military base, where they were tortured and killed within hours.

Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, also known as Madame Agathe (photo taken in Kigali Genocide Centre: James Weis).

Five days later, Belgium, which was the largest troop contributor to the UNAMIR forces, announced that it was withdrawing entirely from the mission, cutting the UN troops from 2 500 to only 250.