Uganda

Region Links: Bwindi

Known as "The Pearl of Africa" (a phrase popularized by Winston Churchill after his 1907 visit), Uganda boasts a remarkable diversity of wildlife, habitats, and adventures.

"Tree-climbing" lions in Kidepo Valley NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Uganda's ten national parks offer visitors classic East African savanna safaris, highland forests with gorillas and chimpanzees, alpine hiking, high mountain peaks, and boating on its Great Lakes.

The country was a British Protectorate from 1894-1962, after which Uganda became an independent country. The 1970s and 1980s were a period of civil unrest and political turmoil in Uganda, which did great harm to its previously world-class national parks and reserves.

Today, Uganda has long-since moved forward from its earlier struggles and progressively protects its natural resources and wildlife, making it a very good destination for eco-tourism.

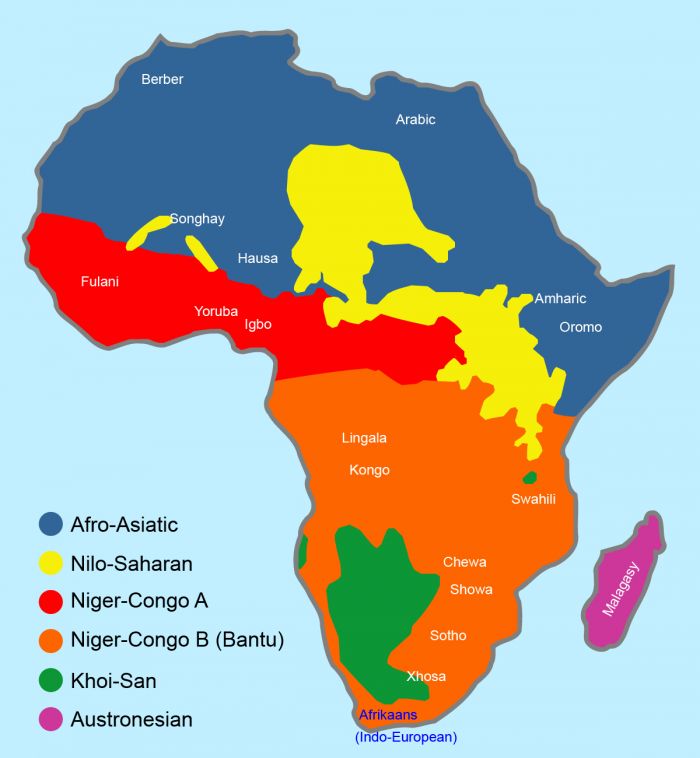

The country's position on the equator and high annual rainfall make it one of the greenest and most fertile countries in East Africa. Uganda is located in Africa's Great Lakes region, which was created as the continent was carved open by the tectonic activity that formed the Great Rift Valley.

Permanent water, including Lakes Victoria, Albert, Edward, and George, numerous small crater lakes, assorted wetlands and numerous rivers, including a portion of the Nile, make up 17% of Uganda's surface area.

Elephant and hippos in the Kazinga Channel, Queen Elizabeth NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Uganda's protected areas are best categorized by habitat type. The country's classic wildlife safari destinations, offering game drives and iconic African species such as lion, elephant, buffalo, hyena, and other plains game include: Queen Elizabeth National Park, Murchison Falls National Park, Kidepo Valley National Park, and Lake Mburo National Park.

In addition to traditional wildlife safaris conducted in 4x4 vehicles in open grasslands and woodlands, Uganda boasts several outstanding closed-canopy forest destinations. These protected forests are mostly located on the western side of Uganda, close to its border with the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and they offer visitors a chance to explore on foot and observe over a dozen species of primate, as well as several hundred species of bird.

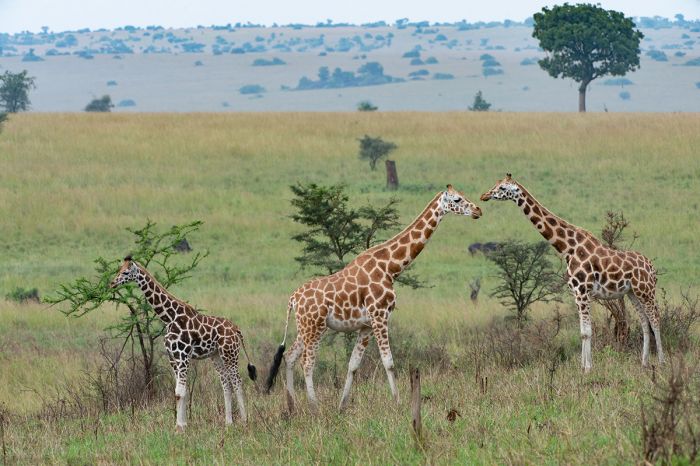

A small population of highly endangered Rothschild's giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi) live in Kidepo National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Uganda's most popular forest ecosystem is Bwindi National Park, which is home to half the world's remaining mountain gorillas and where tourists can partake in a gorilla trek to observe these beautiful animals in their natural environment. It is an experience like no other and highly recommended. More gorilla trekking is offered in the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, a small park in the Virunga Mountains, which span across Uganda, Rwanda and the DRC.

Another forest-based experience is chimpanzee trekking, which, like gorilla trekking, gives an up-close wildlife encounter with Uganda's other great ape species. Several Ugandan parks offer chimpanzee treks, the best of which is offered in Kibale National Park.

A baby mountain gorilla in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Finally, for those who love to explore wild and untouched mountains, Uganda's Rwenzori Mountains on the western side of the country are the highest range in Africa, with six peaks in the top ten highest on the continent.

Guided, multi-day treks are offered, including summit hikes and those that wind around the peaks at lower altitudes. On Uganda's eastern border with Kenya is Mount Elgon, a long-extinct shield volcano with several peaks that can also be explored.

Uganda is an excellent travel destination, offering a diverse array of habitats, wildlife, and experiences and one could easily spend several weeks to see. A smart option is combining Uganda with other nearby countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, or Rwanda.

The Rwenzoris are Africa's highest mountain range.

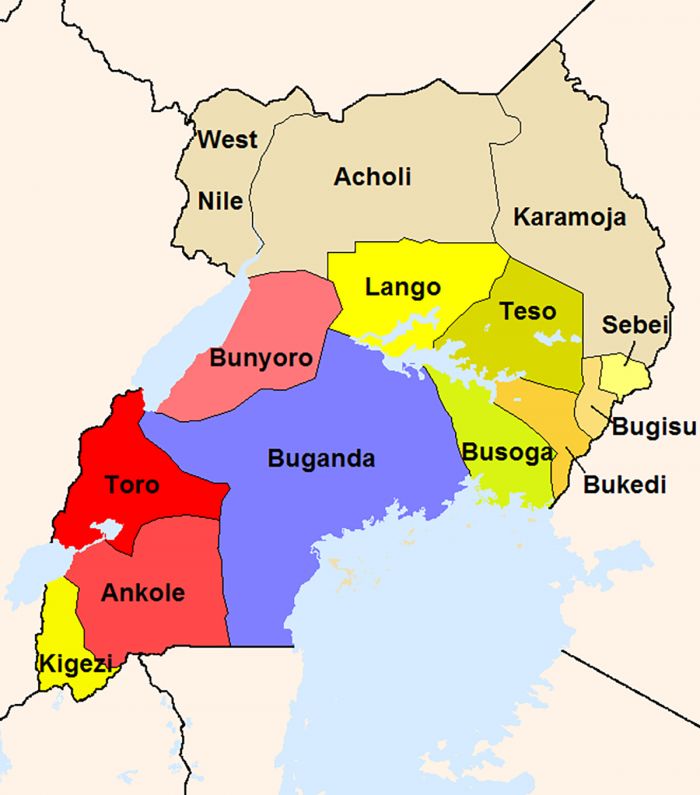

Uganda Regions

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

Join one of the greatest adventures in Africa - a gorilla trek! Bwindi is home to one-half of the world's 1 000 mountain gorillas and observing them up close in the wild is an experience like no other. more

For additional Uganda Regions, check links on the Details Tab...

Read More...

Main: Flora, Geography, Important Areas, National Parks, Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, UNESCO Sites, Urban Areas, Wildlife

Detail: Bigodi, Bwindi, Entebbe, Kampala, Kibale, Kidepo Valley, Lake Mburo, Lake Victoria, Mgahinga, Mount Elgon, Murchison Falls, Ngamba Island, Queen Elizabeth, Rwenzori Mountains, Semliki, Semuliki

Admin: Travel Tips, Entry Requirements/Visas

Geography

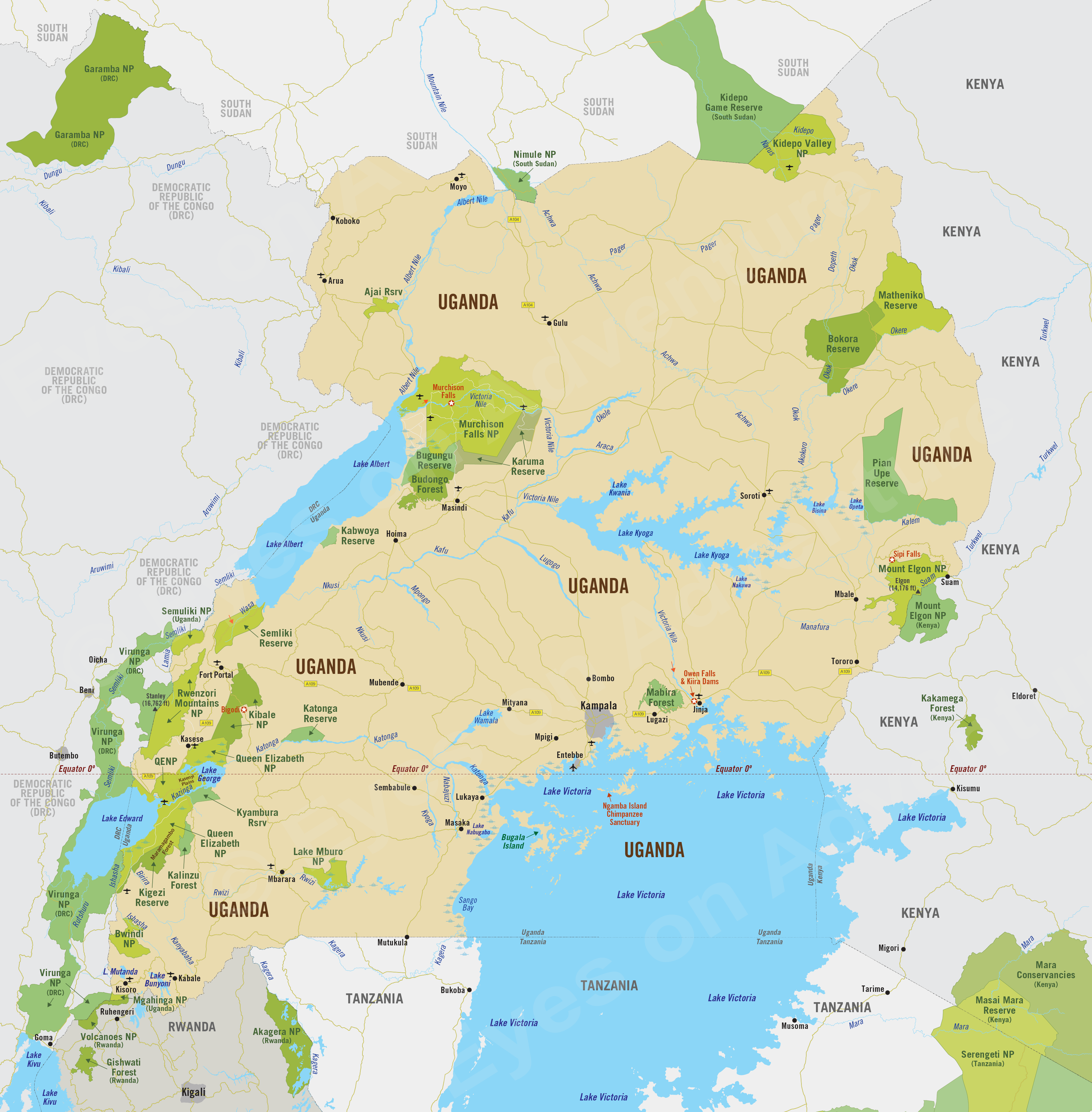

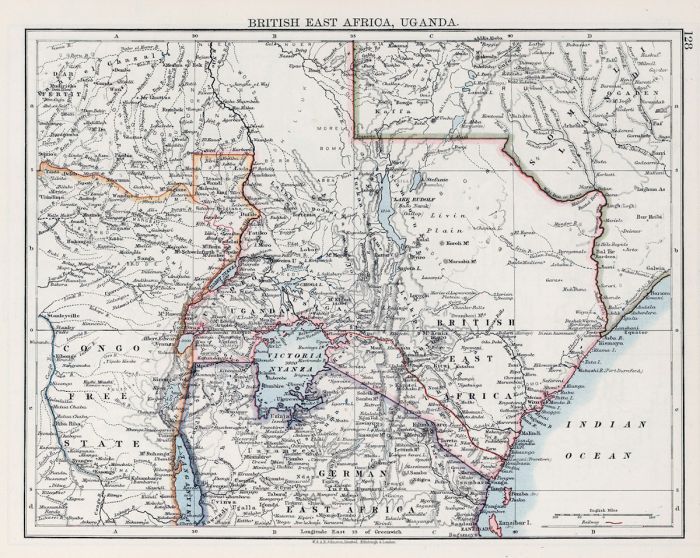

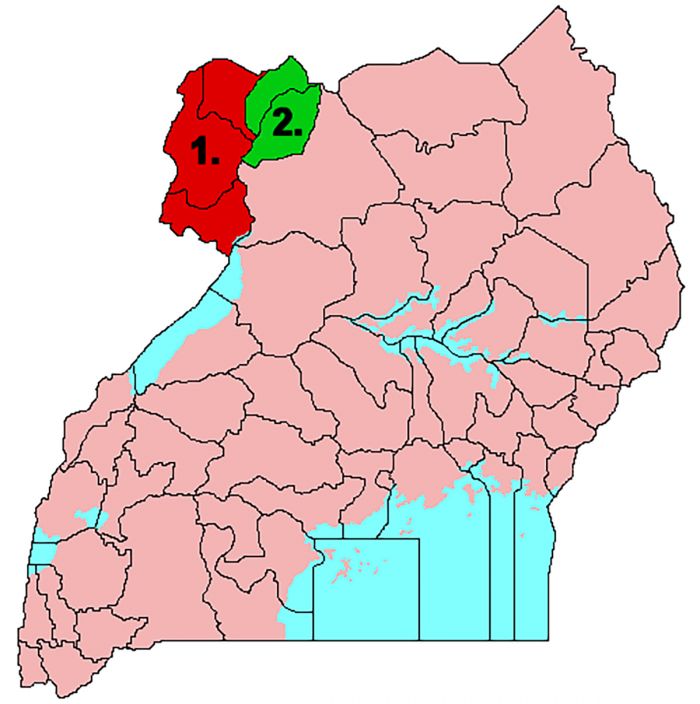

Uganda is a landlocked country located in Central Africa in what is known as the Great Lakes Region, bordered by five countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, formerly Zaire) in the west, Rwanda in the southwest, Tanzania in the south, Kenya in the east, and South Sudan in the north. Lake Victoria covers a large portion of southeast Uganda. The equator passes through the the country about one-quarter of the way north from its southern border.

Much of Uganda lies on a plateau, which is actually an elevated portion of the basin between the eastern and western branches of the East African Rift, which runs from the Red Sea in the far north to Mozambique in the south. The plateau is mainly flat, with elevations that slope gently from around 5 000 feet (1 500 meters) in the south, to around 3 000 feet (900 meters) in the north. Uganda's plateau is flanked by mountains and lakes that fill the valleys.

Murchison Falls on the Victoria Nile River, Uganda.

Uganda's southwest border is defined by mountain ranges that include the Virunga Mountains (on the shared borders between Uganda, Rwanda, and DRC) and the Rwenzori Mountains (on the border with DRC). The Rwenzoris are the highest mountain range in Africa, with its highest peak on Mount Stanley (16 760 feet/5 109 meters) only exceeded in altitude on the continent by Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro (both free-standing volcanos). On the country's eastern border with Kenya is Mount Elgon (14 177 feet/4 321 meters), a massive extinct volcano.

Uganda is a mostly fertile land, receiving ample rainfall over much of its area. About 20% of Uganda's surface area is covered by lakes, the most notable of which is Lake Victoria, Africa's largest and the world's second largest freshwater body (by area). Lake Victoria is shared by Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. Uganda's other major lakes include Lake Albert, Lake Edward, and Lake George, which occupy the valleys of the Albertine Rift on Uganda's western boundaries. The vast, swamp-filled marshes of Lake Kyoga lie roughly in the center of the country.

Margherita Peak in the Rwenzori Mountains, Africa's third highest peak.

There are several major rivers flowing through Uganda, the two most prominent being the Victoria Nile in Central Uganda and the Albert Nile in the northwest. Both of these are the southernmost extensions of the White Nile River, a major tributary of the main Nile River. Uganda's other significant rivers include the Ojok, Pager, and Achwa in the north and the Katonga, Mpongo, and Kafu in the west.

Uganda's southern rivers flow into Lake Victoria, which drains northward via the Victoria Nile River into Lake Kyoga. From there the river traverses north and then west, flowing over the Murchison Falls, before emptying into Lake Albert. Lake Albert drains north via the Albert Nile, which become the Mountain Nile after crossing into South Sudan. Rivers rising in the southwest flow into Lakes George and Edward, which empties north via the Semliki River into Lake Albert. The northern rivers flow south into either Lake Kyoga or north as tributaries of the Nile.

The Victoria Nile River as it leaves Lake Victoria at Jinja.

Flora

A defining feature of Uganda is that it receives substantial rainfall over much of its land. Uganda's healthy local rainfall, combined with its location straddling the equator, makes for a moist and tropical climate that supports year-round vegetation growth. In fact, Uganda is one of the greenest and most fertile countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

The southwest portion of the country is dominated by several mountain ranges, the lower elevations of which are covered closed-canopy forests and rich grasslands. This region has remnants of what was once an expansive lowland and montane forest that spanned from Lake Albert, all the way south into Rwanda and Burundi.

The incredible Afro-montane moorland vegetation of the Rwenzori Mountains.

Most of Uganda's forests were cleared for agriculture over a century ago, but the remaining pockets of forest are now protected and include Bwindi Impenetrable Forest and Semuliki, which is an extension of the lowland rainforests in the Congo Basin to the west.

The southern region, particularly around Lake Victoria, boasts extremely rich soils that originally supported forests and swamps. These forests have mostly been cleared for agriculture, specifically bananas.

Uganda boasts a number of protected forests, including Bwindi, which is home to half the world's mountain gorillas.

Central Uganda is dominated by savanna grasslands, interspersed with open woodlands that support acacia, candelabra, and euphorbia trees. There are large swamps around the fluctuating edges of Lakes Kyoga, Kwania, Bisina, and Opeta, supporting papyrus and rich floodplain grasslands.

Northern Uganda is the country's driest region, with semi-arid desert along the border with South Sudan.

A Rothchild's giraffe next to a candelabra tree in Kidepo National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Wildlife

In the late 1960s, Uganda was visited by over 100 000 tourists per year, but this ended during the political instability during the tumultuous 1970s and 1980s (read more in the History section below). During this difficult period, Uganda's once wildlife-rich national parks were abused, with significant loss of wildlife and rampant encroachment into protected areas. The loss of its wildlife during these two decades put Uganda at a significant disadvantage in terms of wildlife tourism versus competing countries like Kenya and Tanzania.

Beginning in the 1990s, Uganda began re-focusing on conservation of its natural resources and today, although not at the levels of the 1960s in terms of wildlife numbers and diversity, the country's national parks and resident wildlife are again a major draw for international tourists.

An elephant in the grassland savanna of Queen Elizabeth NP - Ishasha Sector (Copyright © James Weis).

The advent of mountain gorilla trekking in the late 1980s was a major driver in rebuilding Uganda's wildlife tourism, as roughly one-half of the world's population of these animals resides in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. Uganda has recently developed its chimpanzee trekking industry (most notably in Kibale National Park) into arguably the best in Africa.

Uganda's wildlife is protected in 10 national parks, which cover a wide range of habitats and species. Four of Africa's Big Five animals (only rhinos excluded) can be seen in several of its parks, while the forested parks offer over a dozen species of primate. Lions are found rather easily in Murchison Falls, Queen Elizabeth, and Kidepo Valley. Cheetah are rare in Uganda and only seen regularly in Kidepo Valley.

A chimpanzee in Kibale National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Roughly 30 species of antelope can be found in Uganda, which equates to around 30 percent of the total for Africa. Commonly seen species in Uganda's four savanna-based national parks include Eland, Defassa waterbuck, Ugandan kob, Jackson's hartebeest, bushbuck, and Bohor reedbuck. Burchell's Zebra, common throughout most of southern and East Africa, are notably absent from most of Uganda and can only be seen in Lake Mburo and Kidepo Valley.

Elephant are found widely throughout Uganda's national parks (except for Lake Mburo), including the 'forest' race in parks such as Bwindi and Semuliki. Both species of rhino are locally extinct in Uganda. Hippos are very common, especially in Murchison Falls, Queen Elizabeth, and Lake Mburo.

Buffalo can be reliably seen in nearly all of the national parks, except sin forested areas, where they do exists but are harder to locate. Giraffe (the localized Rothschild's sub-species) were once common throughout in Uganda, but are now only found in Kidepo Valley and Murchison Falls.

Ugandan kob are found in several of the country's protected areas (Copyright © James Weis).

Birding in Uganda can only be described as outstanding. Uganda is one of Africa's top destinations for birders, offering relatively easy access to avian species not easily seen elsewhere on the continent, as well as a huge number and diversity of species overall.

Over 1 000 avian species are on the Uganda list, an incredible number owing to the country's diversity of habitats, including savanna, rainforest, montane forest, wetlands, and highlands. While the country has only one endemic species (Fox's weaver), there are over 150 species found in Uganda that can not be seen anywhere else in East Africa. The highly sought-after shoebill stork is reliably seen in several wetland areas in Uganda.

Uganda has several reliable sites for seeing the unusual looking shoebill stork.

Protected Areas

Uganda's rich diversity of ecosystems, which includes lakes, swamps, mountains, forests, and savanna, is protected by ten national parks and numerous other wildlife reserves and forest reserves.

Defassa waterbucks in Kidepo Valley National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

National Parks

Following are Uganda's ten national parks (with the type of ecosystem shown in parentheses). Additional information on each is included further below this list:

- Bwindi Impenetrable NP (Forest) - Uganda's top wildlife destination protects rich forest and 11 species of primate. Mountain gorilla treks are the main attraction. Outstanding for birds.

- Kibale NP (Forest) - Protects rich forest and is home to 13 species of primate. Chimpanzee trekking is the main attraction. Excellent birding.

- Kidepo Valley NP (Savanna) - Uganda's most remote wildlife destination, bordering South Sudan. Classic savanna ecosystem with big cats, elephants, buffalo, and a multitude of plains game. Tree-climbing lions. Authentic cultural visits to the Karamojong people.

- Lake Mburo NP (Savanna) - Small park positioned between Kampala and the western parks, with large wetlands habitat. Diverse antelope and great birding. No large predators nor elephants.

- Mgahinga Gorilla NP (Montane) - Small park in the Virunga Mountains bordering Rwanda and DRC. Home to mountain gorillas and other primates. Gorilla trekking, but Bwindi is more often chosen.

- Mount Elgon NP (Montane) - Protects the extinct volcano straddling the border with Kenya. Once Africa's tallest peak, now 4th highest. Great hiking and birding.

- Murchison Falls NP (Savanna) - Uganda's largest and oldest protected area. Four of the "Big Five", big herds, more than 450 bird species. The Famous "Murchison Falls" on the Victoria Nile River.

- Queen Elizabeth NP (Savanna) - Large and diverse ecosystem with multiple 'sectors' bordering Lakes Edward and George. High diversity of mammals and birds. Straddles the equator.

- Rwenzori Mountains NP (Montane) - World class hiking and multi-day mountain trekking in a spectacular setting. Margherita Peak (16 795 feet) is third highest in Africa. Excellent birding.

- Semuliki NP (Forest) - Lowland rainforest bordering DRC. Exceptional birding with several dozen species found nowhere else in Uganda. Cultural visits to Batwa pygmy people.

A herd of Jackson's hartebeest in Kidepo Valley NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Important Areas

Other areas of interest in Uganda include:

- Bugungu Wildlife Reserve (Savanna) - Adjoins Murchison Falls NP and offers good wildlife, including lion, elephant, buffalo and a good variety of antelopes and other plains game. Well-known for chimpanzees.

- Kyambura Wildlife Reserve (Savanna) - Bordering the Kazinga Channel, which is productive for diverse wildlife and birding. Similar wildlife to Queen Elizabeth NP, including lion, buffalo, elephant, and a variety of plains game. Habituated wild chimpanzees can be visited. Good birding.

- Lake Victoria - Africa's largest lake, shared by three countries (49% is in Uganda). Various islands and wildlife/birding areas along its shores.

- Semliki Wildlife Reserve (Savanna) - Grasslands with open acacia woodlands. Game drives will provide views of elephant, buffalo, and other plains game. Nature walks and boating (Lake Albert). Primate walks and excellent hiking. Cultural visits to local communities.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations whose mission is to promote world peace and security through international cooperation in education, the arts, the sciences, and culture. The Convention concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage was signed in November 1972 and ratified by the 189 UN member "states parties".

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area which is geographically and historically identifiable and has special cultural or physical significance. To be selected as a World Heritage Site, a nominated site must meet specific criteria and be judged to contain "cultural or natural heritage of outstanding value to humanity". An inscribed site is categorized as cultural, natural, or mixed (cultural and natural). As of 2021, there were over 1 100 sites across 167 countries.

Uganda has three UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (since 1994, Natural) - Synonomous with the national park, which protects the home of the endangered mountain gorillas.

- Rwenzori Mountains National Park (since 1994, Natural) - Synonomous with the national park, which protects diverse flora and fauna, as well as glaciers, waterfalls, lakes, and pristine montane habitat.

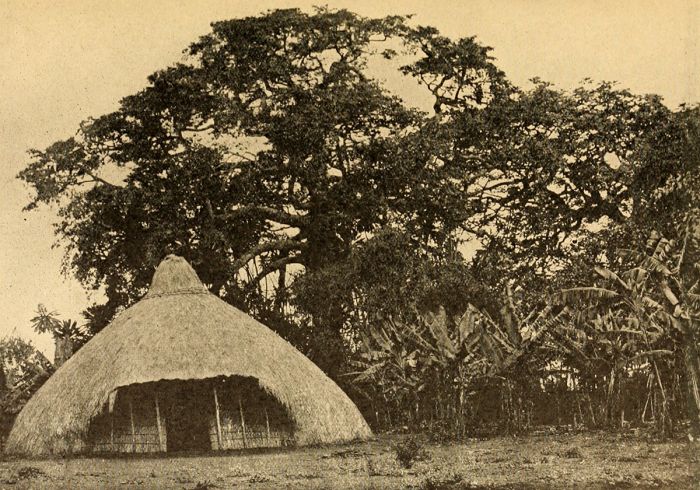

- Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi (since 2001, located in Kampala city, Cultural) - Site of former palace of the Kabakas (kings) of the Buganda Kingdom. The site is a culturally significant spiritual center for the local people.

A sacred ibis along the banks of the Kazinga Channel, Kyambura Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. It was the first of the modern global nature conservation conventions, negotiated during the 1960s by countries and non-governmental organizations concerned about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for birds and other wildlife. The convention is named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, where the convention was signed in 1971.

Presently there are some 75 member States to the Ramsar Convention throughout the world which have designated over 2 300 wetland sites onto the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance.

Uganda has 12 sites designated as Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Sites) as follows.

- Lake Bisina Wetlands - Shallow freshwater lake with papyrus swamp forming part of the Lake Kyoga Basin. Crucial habitat for wading birds, including the shoebill stork, as well as numerous fish species that have become extinct in the large lakes of Kyoga and Victoria. The lake is important for surrounding communities for fishing, and water for domestic use and livestock. (209 sq miles/542 sq kms)

- Lake George - Network os rivers flowing from the Rwenzori Mountains supplies permanent swamps on Lake George. Crucial habitat for numerous large mammal species and important site for resident and migratory birds. Threats include mine water seepage, agricultural runoff, and effluent inputs. Partially protected by Queen Elizabeth National Park. (384 sq miles/150 sq kms)

- Lake Mburo-Nakivali Wetland System - Open and wooded savanna and combination of seasonal and permanent wetlands, including five lakes (Lake Mburo by far the largest). Habitats have a high biodiversity, including globally threatened resident and migratory species of bird, such as shoebill stork, several threatened fish species. Immense socio-economic value as a water source for people. Threats include hunting, over-fishing, habitat destruction. (104 sq miles/169 sq kms)

- Lake Nabugabo Wetlands - Situated directly north and contiguous with the Nabajuzi Wetlands. Lake Nabugabo and 3 smaller freshwater lakes separated from Lake Victoria by a sand bar 1.2 miles (2-kms) wide. No surface outflows from the lakes, just seepage via the sand bank. The lakes have been separated from L Victoria for ~3 700 years. Several endemic fish remain that are now extinct in L Victoria due to the introduction of the Nile perch. Lakes are important for migratory birds, some globally threatened, and are also habitat and breeding grounds for shoebill storks. (85 sq miles/220 sq kms)

- Lake Nakuwa Wetlands - Permanent wetland associated with Lake Kyoga system. Dominated by papyrus swamps, with a number of satellite lakes and pools of water containing floating papyrus. Habitat for sitatunga antelope, crocodile, and a large diversity of cichlid fishes no longer found in Lake Kyoga or Lake Victoria that were protected by thick aquatic vegetation around these lakes, which prevented the introduced Nile perch from spreading here. One of the most pristine wetlands remaining in Uganda. (352 sq miles/912 sq kms)

- Lake Opeta Wetlands - One of the most important intact wetland marshes in Uganda, with aquatic hippo grass to the east and dry grassland savanna to the south. Provides important habitat for numerous birds, including breeding ground for Uganda's sole endemic species, Fox's weaver. Also provides crucial refuge for numerous fishes that have gone extinct in the larger lakes, including Kyoga and Victoria. Provides wthe only dry-season water for animals in the Pian-Upe Reserve. (266 sq miles/689 sq kms)

- Lutembe Bay Wetlands - Located between Entebbe and Kampala at the mouth of Murchison Bay on Lake Vocyoria. Shallow swamp cut off from the main body of L Victoria by a papyrus island. Habitat for globally threatened birds, endangered cichlid fishes, and over 100 species of butterfly. Breeding grounds for lungfish. Threatened by the large population of people living in close proximity. (0.4 sq miles/1 sq km)

- Mabamba Bay Wetlands - Extensive marsh and long, narrow bay fringed with papyrus on Lake Victoria shore very close and southwest of Kampala. Shoebill storks are fairly easy to locate and habitat supports 190 000 birds, including several globally threatened species. Poaching, over-fishing, agrochemicals used for nearby flower farms, and over-utilization of papyrus are main threats. (9 sq miles/24 sq kms)

- Murchison Falls-Albert Delta Wetland - Site spans from top of the Murchison Falls to the delta of the Victoria Nile River as it enters Lake Albert. Important habitat for waterbirds, including the shoebill stork, pelicans, darters, various herons. Spawning and breeding grounds for indigenous fishes. Feeding and watering refuge for wildlife, especially in dry season. Threats include livestock grazing, illegal hunting, and over-fishing. Fishermen-crocodile conflicts are common. (67 sq miles/173 sq kms)

- Nabajuzi Wetlands - Long, narrow stretch of swamp along Lake Victoria shoreline due east of Masaka town and extending to Katonga and Nabajuzi Rivers. Crucial spooning grounds for mudfish, lungfish and supports globally threatened birds. Protects good numbers of sitatunga antelope. Pollution and over utilization of fish and water by surrounding towns are threats. (7 sq miles/18 sq kms)

- Rwenzori Mountains - High annual rainfall and snowmelt creates various wetlands in these "Mountains of the Moon", including peatlands, lakes, and tundra. Habitats are crucial for protecting 21 species of small mammal, numerous species of indigenous fish and bird. Protected as a national park and is also a World Heritage Site. (58 sq miles/995 sq kms)

- Sango Bay-Musambwa Island-Kagera River Wetland - Mosaic of wetlands, including swamp forest, papyrus swamp, herbaceous swamp, with palms and seasonally flooded grasslands, rocky and forested shorelines, and three rocky islets just offshore in Lake Victoria. Rich biodiversity. Habitat for huge numbers of waterbirds, as well as elephants and primates. (213 sq miles/551 sq kms)

A Jackson's three-horned chameleon in Bwindi Impenetrable NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Urban Areas

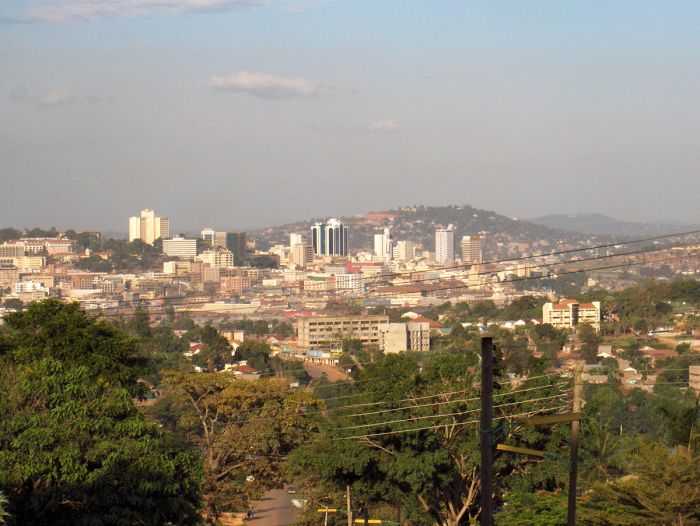

Uganda has only two substantial urban areas, both of which are located along Lake Victoria. See details below.

- Entebbe - The smaller of two notable cities in Uganda, both of which are located on the shores of Lake Victoria in close proximity to one another.

- Kampala - Uganda's capital and by far its largest city, though most international visitors fly into Entebbe, where the main airport is located.

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park

The Bwindi Forest covers 124 square miles (321 sq kms) and is one of the world's most biodiverse ecosystems, protecting more than 1 000 flowering plant species, more than 200 species of tree, and over 100 species of fern. Bwindi dates back 25 000 years, making it one of the oldest forests on earth.

Bwindi is Uganda's top wildlife destination for one reason: the mountain gorillas that live in its rich, Afro-montane rainforest. Gorilla trekking has become very popular in both Uganda and neighboring Rwanda. These treks involve hiking with expert guides to visit one of the "habituated" gorilla families in the forest. Participants are able to spend time on the ground with wild gorillas, often only 10 feet from these incredible animals. The experience is unlike anything else offered in Africa or the world.

Bwindi offers incredible mountain gorillas trekking (Copyright © James Weis).

Besides the main attraction of mountain gorilla trekking, Bwindi is also home to 10 additional species of primate, including a healthy population of some 400 chimpanzees.

Bwindi also offers spectacular birding, especially with a local guide. There are around 350 species to be found in Bwindi, including two dozen range-restricted species. Nature hikes in the forest will also provide a good chance of seeing chimpanzees, monkeys, and some of Bwindi's 200+ species of butterfly.

Read full details on the gorillas, gorilla trekking, and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park here.

L'Hoest's monkeys are one of 11 species of primate found in Bwindi.

Kibale National Park

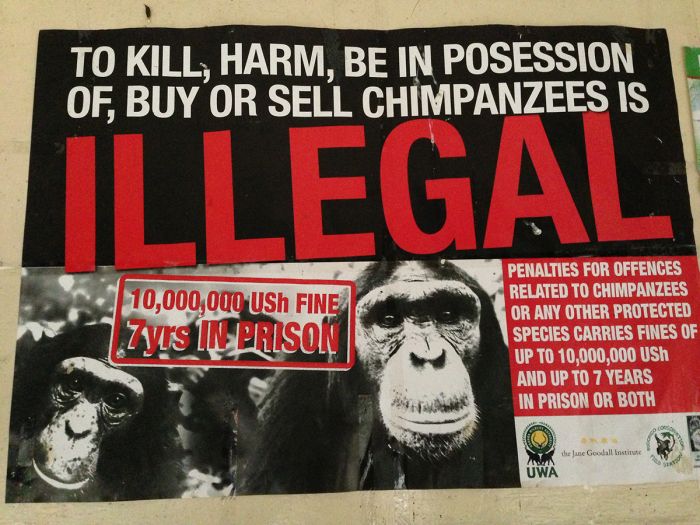

Kibale offers Uganda's "other" great primate experience: chimpanzee trekking. Some 1 500 chimpanzees are protected in the Kibale Forest and guided treks, sometimes with researchers, but always with expert guides, allow visitors to see our closest extant species (chimps are 98% genetically identical to Homo sapiens) in their natural habitat.

The Kibale Chimpanzee Project, established in 1987, is an ongoing, long-term study of the behavior, physiology, and ecology of Kibble's chimpanzees. The revenue earned from chimpanzee trekking supports the research project and helps protect the forest habitat. The chimps in Kibale are well-habituated due to the long-term presence of the researchers and now tourists. The chimps are mainly very relaxed and, when on the ground, provide incredible up-close observation.

The chimpanzee trekking experience in Kibale is outstanding (Copyright © James Weis).

While gorilla trekking (in Bwindi or in Rwanda) is certainly described as incomparable, the full-day chimpanzee experience in Kibale rivals or even exceeds that of gorilla trekking. A gorilla trek can take the better part of a day, but the actual interaction time with the gorillas is limited to one hour, while the full-day chimp trek (called "chimp habituation experience") involves following and observing chimpanzees for the better part of the daylight hours.

Besides chimpanzees, Kibale is home to 60 mammal species, including twelve additional species of primate. Primates that are regularly seen in on a hike or chimpanzee trek in Kibale include red-tailed monkey, black-and-white colobus monkey, red colobus monkey, L'Hoest's monkey, blue monkey, grey-cheeked mangabey, and olive baboon. Bush baby and potto are nocturnal primates, so are infrequently seen except on a guided night walk, which almost assuredly will provide views.

A chimpanzee in Kibale National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Other mammals in Kibale include elephant (forest race, seldom seen), lion and leopard (both are rarely seen), buffalo, bush pig, hippo, warthog, red, blue, and Peter's duiker. Butterflies are abundant and incredibly diverse, with over 250 species recorded. Birding in Kibale is sensational, with over 375 species possible, including many regional endemics.

A red-tailed monkey in Kibale National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Bigodi Wetland

A must-do for birding enthusiasts or keen nature lovers is a guided walk at the nearby Bigodi Wetland Sanctuary, which protects the Magombe Swamp. The four-hour trail is laid out to cover a good portion of this rich swamp habitat and the expert guides will gladly point out a large variety of birds (30-40 species easily), many of which will be "specials" at the eastern limit of their range.

In addition to birds, Bigodi will almost surely provide views of several monkey species, the most likely being red-tailed, L'Hoest's, black-and-white colobus, and grey-cheeked mangabey. There are myriad butterflies, flowers, and fish that the guides can point out. If you're lucky, you may see a sitatunga antelope or one of the mongoose species that live here. Fees charged for the trail are used for community projects in Bigodi.

The Bigodi Wetland Sanctuary offers guided nature walks (Copyright © James Weis).

Weather and When to Go

Kibale experiences a moist tropical climate all year, with stable temperatures averaging 78-83°F (26-28°C) during the day and dropping to 57-61°F (14-16°C) at night. There is no actual dry season, with rain possible throughout the year, but Jan/Feb and Jun/Jul are the driest months. Waterproof clothing is recommended for chimp trekking regardless of the time of year.

Close-up of a chimpanzee foot, Kibale NP (Copyright © James Weis).

How to Get There

Kibale is best reached via flight (scheduled or charter) from Kampala/Entebbe to Fort Portal. The flight duration is around 1.5 hours, with a short 40 minute drive to the park. The trip from Kampala/Entebbe to Kibale by road will take 4.5 hours.

Overall, the experience at Kibale, including a visit to Bigodi, is something that should not be missed. Combining a few days in Bwindi with a few days at Kibale will give a forest exploration experience that is arguably unmatched in Africa.

A warning sign posted in Kibale NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Kidepo Valley National Park

Uganda's most remote national park is the 552-square-mile (1 430-sq-km) Kidepo Valley, located in the far northeast corner of the country, on the border with South Sudan and a stone's throw from the Kenya border. This is the Karamoja region and home to the Karamojong people, whose villages offer an authentic cultural experience for visitors to the park.

Kidepo's remote location means it is much less visited than the parks on Uganda's western side, but for those that take the time, it offers one of the best wilderness experiences anywhere in Africa. The park offers excellent wildlife viewing, with an astounding diversity of species, plus raw mountain scenery, and outstanding birding.

Kidepo Valley has some "tree climbing" lions (Copyright © James Weis).

The park's rugged terrain includes several substantial peaks, including Mount Morungole, which rises 9 022 feet (2 750 meters). Two river valleys define the park's main game-viewing regions, with the Narus River Valley in the southwest and the Kidepo River Valley in the northeast. Both rivers are seasonal and stop flowing during the dry months, but leave behind crucial pools that sustain the wildlife.

Kidepo's predominant habitat is open grassland savanna, interspersed with sparse woodlands, thick stands of miombo woodland, and rocky outcrops. The river valleys support riparian woodland and towering borassus palms. The higher elevations support montane forests.

A buffalo is attended by a small flock of piapiac birds (Copyright © James Weis).

There are 77 species of mammal in Kidepo, including twenty species of predator. Lions are fairly easy to locate and this is the only place in Uganda where cheetah are found. Other predators found nowhere else in Uganda include black-backed jackal, caracal, bat-eared fox, and aardwolf. Both spotted and striped hyena are here, as well as leopard, side-striped jackal, genets, several species of mongoose and sometimes African wild dogs are seen.

Antelopes are well represented and several, including both greater and lesser kudu, mountain reedbuck, and Guenther's did-dik are found nowhere else in Uganda. Other antelopes found in Kidepo include eland, bushbuck, Defassa waterbuck, Grant's gazelle, Jackson's hartebeest, klipspringer, oribi, common duiker, and bohor reedbuck.

The regionally endemic Rothchild's giraffe are found in Kidepo Valley (Copyright © James Weis).

Elephants are common, especially during the rainy season when Kidepo's grasses are a favorite food for them. Large numbers of buffalo can also be seen, with groups of bachelor bulls spending time away from breeding herds that can number several hundred.

Other plains game includes zebra, Ugandan kob, warthog, and a small population of Rothschild's giraffe. There are several primate species found in Kidepo, including the localized patas monkey. Both black and white rhinos once roamed Kidepo, as did roan antelope, but these are now extinct due to hunting years ago.

Kidepo's bird checklist is outstanding, which, at around 450 species, is only rivaled in Uganda by Queen Elizabeth National Park. Many of Kidepo's "specials" are dry-land species that are not found in any other region in the country.

View over grassland savanna in Kidepo Valley National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Weather and When to Go

Kidepo is located in a semi-arid region and experiences only one wet season, which spans from April thru August, when afternoon showers are common. The dry season is from September thru March and during the months of December, January, and February, there is virtually no rain. The dry season is an excellent time to visit, as most of the wildlife congregates in the Narus River Valley for water, as the Kidepo River becomes dry.

Temperatures are warm all year, averaging 80-86°F (27-30°C) during the day and dropping down to 60-65°F (16-18°C) at night. Daytime temps can reach as high as 105°F (41°C) during the dry months of January and February.

A cultural visit to a Karamojong village near Kidepo Valley NP (Copyright © James Weis).

How to Get There

Visiting Kidepo Valley is best done on a chartered flight from Kampala. The flight takes 2-2.5 hours. Driving is possible but not recommended, as the roads are not great and the trip will take between 7-10 hours. It is possible to fly from Kidepo to Murchison Falls if one is doing a circuit of Uganda (a great experience and highly recommended).

Kidepo Valley is one of the few places in East Africa to see the patas monkey (Copyright © James Weis).

Queen Elizabeth National Park

Queen Elizabeth National Park (QENP) is Uganda's most popular savanna-ecosystem safari destination. The park covers 764 square miles (1 978 sq kms) with a number of natural and man-made barriers dividing QENP into various "sectors".

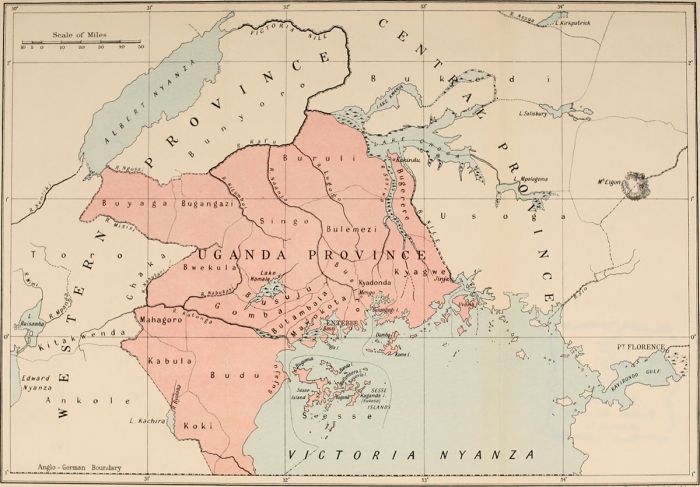

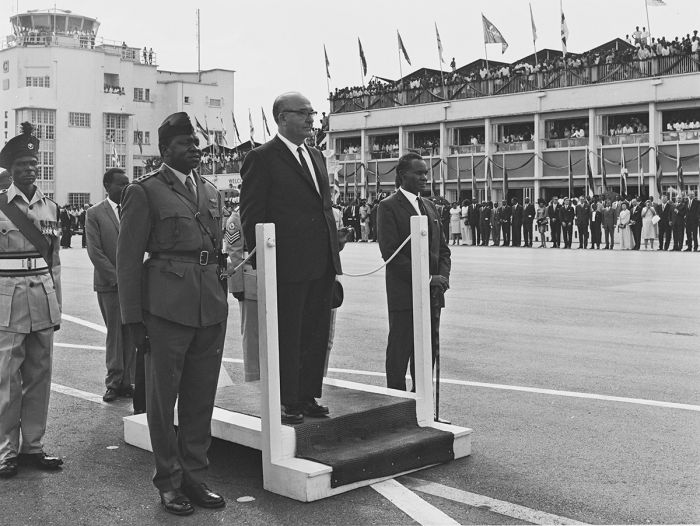

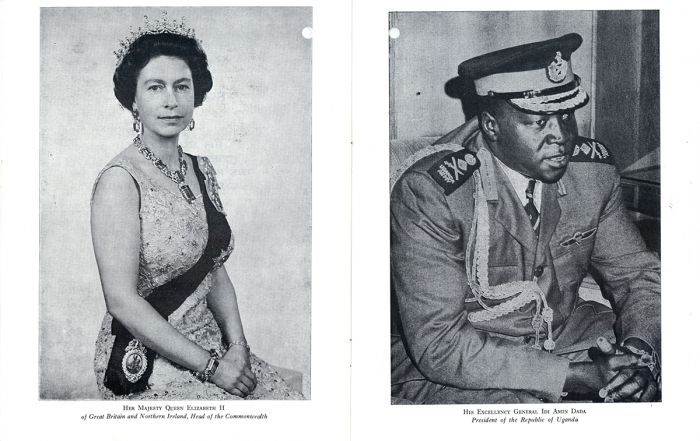

Originally protected as two separate game reserves (Lake George and Lake Edward Game Reserves declared by the Belgian Colonial Administration) in the 1920s, it became a single protected area dubbed Kazinga National Park in 1952.

An elephant along the bank of the Kazinga Channel, Queen Elizabeth NP (Copyright © James Weis).

The park was renamed in 1954 to commemorate a visit by the British Queen. QENP was then briefly renamed as Rwenzori National Park (during the Idi Amin regime), which is confusing, as in 1991, the upper slopes of these nearby mountains were also declared as Rwenzori National Park!

QENP is primarily dominated by an open grassland, savanna habitat, but is incredibly diverse, with lake front, extensive wetlands, dense acacia woodlands, and vast tracts of forest. There are over ten crater lakes in QENP (some 35 in the region, as well as numerous dry calderas), caused by volcanic activity in the region several hundred thousand years ago.

One of many crater lakes in Queen Elizabeth National Park.

QENP Wildlife

Owing to its extremely high level of habitat diversity, QENP is home to some 95 mammal species, the most for any park in the country. Predators are well represented, with more than twenty species, including lion, leopard, spotted hyena, and side-striped jackal. Some of QENP's lions (in the Ishasha Sector) are "tree-climbing" and spend their time during midday relaxing on the limbs of sycamore figs and albezia trees.

Antelopes are also here in abundance, with the most common species being Ugandan kob, topi, Defassa waterbuck, and bushbuck. The sitatunga, an aquatic species can sometimes be found in the papyrus swamps around Lake George. Other herbivores include buffalo, which can be found in healthy herds throughout much of the park. Several species of duiker are found in the Maramagambo Forest in the south. Elephants are commonly seen throughout the park.

A leopard in repose in a large candelabra tree in Queen Elizabeth National Park.

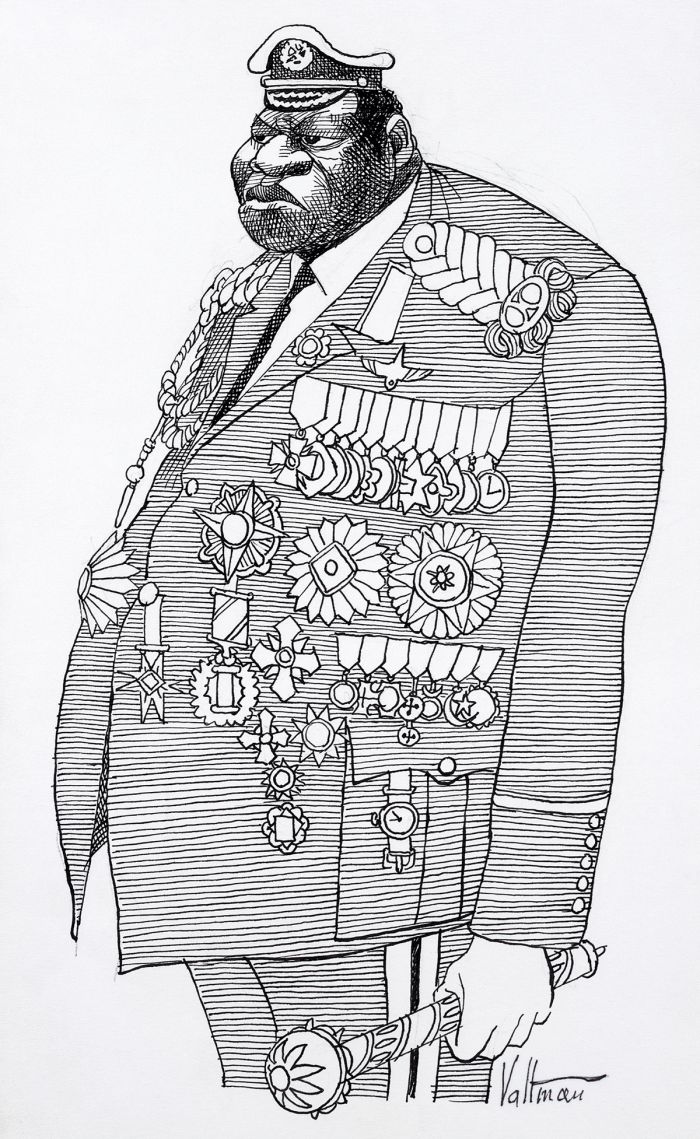

Wildlife in the park suffered greatly during the Amin presidency. Elephants were especially hard hit, with ivory poaching reducing their numbers in QENP from some 4 000 in the late 1950s, to only 100 or so individuals by 1980. Buffalo numbers were reduced by 50% from around 20 000 during the same period. Wildlife has since recovered, with elephants now numbering around 2 500, buffalos numbering over 10 000, and hippos at around 5 000. There are an estimated 200+ lions in the park.

There are ten species of primate in QENP, including chimpanzee, red-tailed monkey, L'Hoest's monkey, vervet monkey, blue monkey, olive baboon, and black-and-white colobus.

Ugandan kob in the grasslands of QENP's Ishasha Sector.

Notably absent from QENP are several iconic species, including giraffe and zebra, both of which were poached to extinction during Uganda's long and tumultuous civil war years. Also missing are rhinos, which were also poached out. The lack of rhinos is the main reason that many areas in the park are dominated by candelabra trees (Euphorbia candelabrum), which are inedible to most animals, but are a favorite of black rhinos.

Interestingly, one species that was, until quite recently, notably missing from QENP, is the nile crocodile. The crocodiles' absence during the colonial times, as well as any archeological evidence of their existence in the area seemed unexplainable, especially since the region had near-perfect habitats for the crocs.

A nile crocodile in Queen Elizabeth National Park.

It was later determined that during the most recent period of heavy volcanic activity around Lakes George and Edward (some 7 000 years ago), the entire region was decimated in terms of animal and plant life. Most species were subsequently able to recolonize the region, but crocodiles faced impassable barriers, including large tracts of forest, as well as rapids and gorges along the waterways leading to the lakes.

In the 1980s, widespread destruction of riparian forests along the Semliki River allowed crocodiles to migrate along the cleared banks of that river and the first appearance of crocodiles in Lake Edward was in the late 1980s. Today, nile crocodiles are common in both Lake Edward and Lake George, as well as in the Kazinga Channel that connects the two lakes.

Buffalos cooling off in the Kazinga Channel, Queen Elizabeth NP (Copyright © James Weis).

As would be expected in a national park with a diversity of habitats, QENP is spectacular for birding. Over 600 species have been recorded, which it the most for any protected area in Uganda. QENP's large number of birds is a reflection of its varied habitats that include lakes, wetlands, rivers, forest tracts, and grasslands.

A boat trip on the Kazinga Channel is a particularly great way to get good views of waterbirds, while the Maramagambo Forest will yield excellent results for rarer species and 'specials'.

Queen Elizabeth NP offers excellent birding; here a gray crowned-crane.

QENP Sectors

Queen Elizabeth NP is partitioned into several sectors by a series of natural dividers. The Kazinga Channel is the most obvious barrier, effectively dividing the park into a northern and southern sections. The two main parts of the park are linked only by a bridge over the channel along the road connecting Kasese and Mbarara.

Within the two main park sections (north and south) are several more focused 'sectors', each of which is discussed below with regards to habitat, wildlife and activities.

A hamerkop with its catch (a barbel) on the bank of the Kazinga Channel (Copyright © James Weis).

Ishasha Sector

The Ishasha Sector is located in the far southwest of QENP, and although commonly overlooked and the least visited, its plains are some of the most beautiful in the country and they offer good wildlife viewing. There are two excellent game-drive circuits, one to the north of Ishasha Camp and the other heading south, and each covering around 12 miles (20 kms). The southern loop passes thru productive plains use by big herds of kob (which means good chances to see lions), while the northern loop is generally more productive overall, with floodplains and wetlands.

Ishasha is perhaps best known for its 'tree-climbing' lions. Lions do not typically spend any time in trees, except perhaps in an effort to steal a leopard's food, and tree-climbing lions are only found in a few places in Africa (Lake Manyara is another such location). The reason that some lion prides habitually spend time relaxing in trees is a topic of speculation, with theories including evasion of biting insects or to stay cool, but one thing seems clear: it is a learned behavior that is passed down and prides exhibiting this behavior continue to do so over time.

The Ishasha Sector is best known for its "tree-climbing" lions.

The banks of the Ishasha River, which feeds into Lake Edward, provide good wildlife viewing and the river supports a healthy hippo population. The riparian forests along the river are also home to good numbers of bushbuck and black-and-white colobus monkey, as well as diverse birds. East from the river are the Ishasha Plains, which are popular with large herds of Ugandan kob, buffalo, waterbuck, and topi. Elephants are also common, especially during and after the rains.

The Kigezi Game Reserve borders the Ishasha Sector to the east, forming a buffer for wildlife between QENP and the heavily populated public lands further east.

Verdant plains and candelabra trees along Lake Edward, Queen Elizabeth NP.

Maramagambo / Kyambura Sector

The southeast section of QENP is dominated by the incredible rich and biodiverse Maramagambo Forest. Guided walks in the forest are the best way to experience the birds and animals, but trails can be walked without a guide. There are plenty of primates, including chimpanzees, L'Hoest's monkey, black-and-white colobus, vervet monkey, and red-tailed monkey.

Other forest mammals include yellow-backed duiker, Bates' pygmy antelope, and giant forest hog. The forest birding is incredible and only exceeded in terms of elusive Central African species by the Semuliki Forest. A birding guide is highly recommended for identifying the myriad shy and elusive forest species in Maramagambo.

The Kyambura River Gorge.

North of Maramagambo Forest is the Kyambura Gorge, which is carved out by the Kyambura River and forms the border between QENP and the Kyambura Reserve to the east. The gorge is home to a habituated community of chimpanzees and guided chimpanzee treks (permits required) in the forested river gorge are the major tourist draw for this sector of the park.

East of the gorge is the Kyambura Reserve, which is primarily a savanna ecosystem, but not especially notable for its wildlife. There are several crater lakes in the reserve that provide good birding, especially for waterbirds and often flamingos.

Chimpanzees in the Kyambura River Gorge.

Mweya / Northern Sector

North of the Kazinga Channel, which connects Lakes Edward and George, is QENP's Northern Sector. This region of the park can be further divided into two popular sub-sectors: the Mweya Peninsula and the Kasenyi Plains. Mweya was once the site of the QENP headquarters (which has now moved) and the Northern game drive circuit between Mweya and the Kasenyi Plains is still the most visited tourist area of the park.

The Mweya Peninsula is a small, wedge-shaped bit of hilly land jutting out into northeast Lake Edward from the northern side of the mouth of the Kazinga Channel. The views from the peninsula are spectacular across the channel and lake and to the north, the Rwenzori Mountains. The network of game-viewing tracks leading from Mweya along the northern banks of the Kazinga Channel will provide abundant game and good birding.

Crater lake Kitagata in Queen Elizabeth's Mweya Sector.

Mweya's location at the confluence of the Kazinga Channel and Lake Edward is very popular with wildlife, and species such as elephant, buffalo, Defassa waterbuck, and warthog are a near certainty. Hippos are also common at Mweya. Lion and spotted hyena sightings are a good possibility at Mweya and along the game drive roads north of the channel and west of the main Kasese road.

East of the Kasese Road, which bisects the Northern Sector, is the most popular game drive area in QENP: The Kasenyi Plains. These plains stretch from the road all the way to Lake George, and are home to large concentrations of plains game. Large herds of Ugandan kob use this grassland savanna as their breeding grounds, with thousands congregating here at times. Buffalo are also fond of this area for its rich grazing.

Elephants in the Kazinga Channel, Queen Elizabeth NP.

Reaching the Kensenyi Plains takes about an hour from the Mweya Peninsula, and exploration as early as possible in there morning will provide the best chance of seeing Kasenyi's lions, which do well here with all the prey species. Spotted hyenas are also resident in good numbers. Birding in Kasenyi is also very good, with numerous grassland species.

North of Lake George is an extensive wetland that is almost totally inaccessible to tourists. The main attraction in the swamp is the incredible shoebill stork, which thrives in this remote area. Sitatunga antelope, an aquatic species, are also found north of the lake and waterbirds are prolific. It may be possible to reach the southern end of this swamp in a good 4x4 vehicle, depending on the time of year and how much water exists.

A yellow-billed stork seen on a boat cruise on the Kazinga Channel (Copyright © James Weis).

Weather and When to Go

QENP is a year-round destination, but rainfall can occur at any time throughout the year. The months with the least chance of rainfall are June/July and January/February. The heaviest rains occur from March thru May and again mid-August thru November. The climate in QENP is tropical all year, with static temperatures year round, averaging 82-88°F (28-30°C) during the day and 60-68°F (16-20°C) at night.

Wildlife viewing in QENP is best, especially around the rivers and lakes, during the dry periods, but the park is most scenic during the rainier months. Chimpanzee trekking and forest hiking are also much better when the trails are dry versus after heavy rains.

Hippos in the Ishasha River, Queen Elizabeth National Park.

How to Get There

QENP is reachable by either road or air. Those on a circuit of Uganda's wildlife regions often arrive from the north, after visiting Murchison Falls National Park and head to Bwindi after visiting QENP. Driving to QENP from Kampala takes a minimum of six hours, while a flight from Kampala takes 1-2 hours depending on the aircraft.

The Kazinga Channel is great for seeing a diversity of wildlife, including birds (Copyright © James Weis).

Murchison Falls National Park

Covering an area of 1 505 square miles (3 898 sq kms), Murchison Falls National Park (MFNP) is Uganda's largest protected area. The park straddles the Victoria Nile River as it approaches Lake Albert just to the west. The famous waterfall, which gives the park its name, is the main attraction for most tourists, but the park also offers excellent game viewing, as well as boating on the river.

Bordering MFNP on the south and east are three buffer reserves: Bugungu Wildlife Reserve (183 sq miles/474 sq kms), Karuma Wildlife Reserve (262 sq miles/678 sq kms), and the Budongo Forest (318 sq miles/825 sq kms). Together with the national park, this Greater Murchison Falls Conservation Area protects a significant area with diverse habitats and wildlife.

The famous Murchison Falls which gives the national park its name (Copyright © James Weis).

History of MFNP

The first foreigners to visit the MFNP region were John Speke and James Grant, who arrived in 1862. The famous explorers Samuel and Florence Baker arrived in 1863 on their expedition to discover the source of the Nile River. The Bakers became the first Europeans to see the narrow waterfall plunging thru a gorge on the Victoria Nile, which they named the Murchison Falls after the then-president of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Roderick Murchison.

During the period between 1907 and 1910, the local human population of a huge area (some 5 000 sq miles/13 000 sq kms) that includes present-day MFNP were evacuated due to an outbreak of "sleeping sickness" (African trypanosomiasis), which is caused by the tsetse fly. In 1910, the land south of the Nile River was declared as the Bunyoro Game Reserve and in 1928, the boundaries were extended to include the land north of the river.

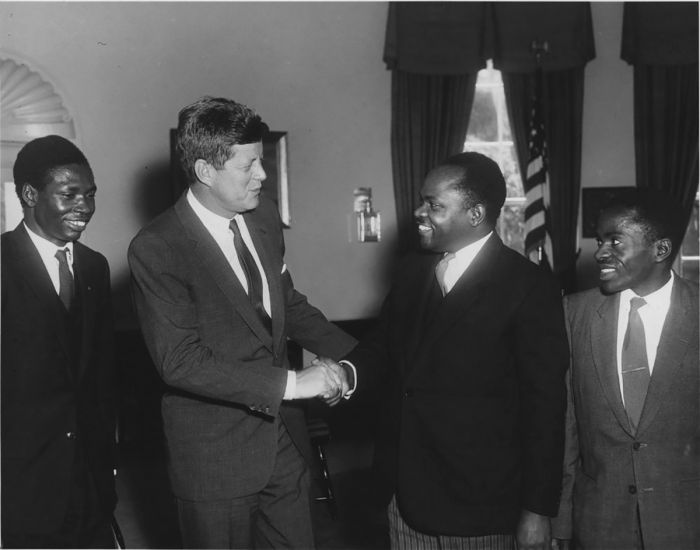

In 1952, the British Colonial Administration established the National Parks Act of Uganda and the Bunyoro Game Reserve was renamed as Murchison Falls National Park. During the Idi Amin regime in the 1970s, MFNP was renamed as Kabalega Falls, after the former Omukama (King) of the Bunyoro Kingdom, but this name fell into disuse after the ousting of President Amin in 1979.

View upriver to the Murchison Falls.

The Waterfall and Nile River

The Murchison Falls are an impressive sight to see, as the water of the 165-foot-wide (50-meter-wide) Victoria Nile River is forced through a narrow gap in the rocks spanning a width of only 23 feet (7 meters) and then falling 141 feet (43 meters) to the continuing river below. The rush of the huge volume of water crashing thru such a narrow gorge causes a deafening roar and copious rising spray.

The waterfall was famously featured in the 1951 British-American adventure film The African Queen, which starred Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart. The falls were even more powerful in those days, but in 1962, massive flooding cut a second channel into the river above the falls, creating the smaller Uhuru Falls that is situated 650 feet (200 meters) to the north.

The Victoria Nile River as it enters the Murchison Falls (Copyright © James Weis).

MFNP is divided into a northern and southern sector by the east-to-west flowing Victoria Nile River. The northern section is defined by tall-grass savanna with sparse acacia scrubland, isolated patches of borassus palms, and riparian woodland. The southern section is dominated by more consistent woodlands that become denser as one moves further south from the river, eventually becoming closed-canopy forest.

The Victoria Nile River just below the Murchison Falls (Copyright © James Weis).

Wildlife in MFNP

In the 1960s, MFNP was one of Africa's most popular wildlife destinations, with huge numbers of animals and several outstanding tourist lodges. Elephants in particular were abundant, with herds of several hundred not uncommon and a total population of some 12 000 in the park. In the late 1960s, a park census revealed 10 000 Ugandan kob, 30 000 buffalo, 12 000 hippo, 16 000 Jackson's hartebeest, 11 000 warthog, and healthy populations of Rothschild's giraffe and both black and white rhino species.

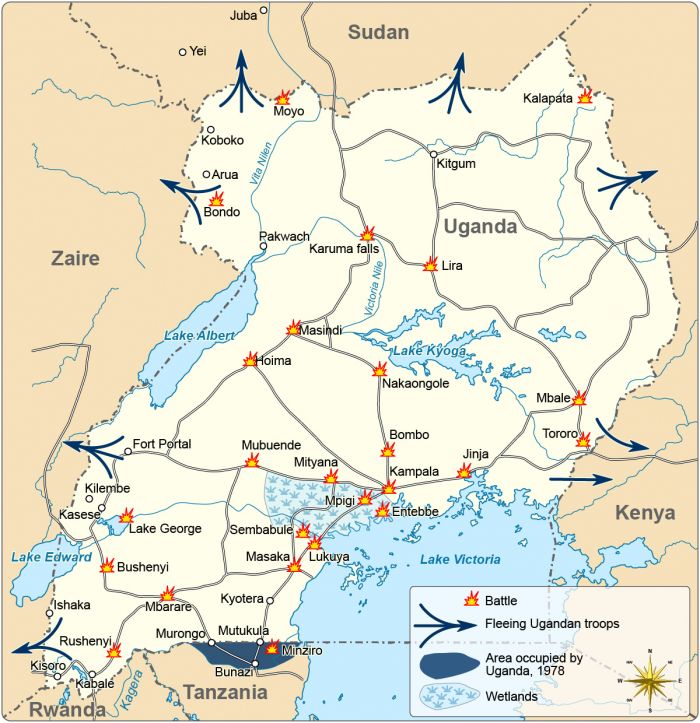

Shortly after the 1971 coup that gave Idi Amin complete power in Uganda, foreign visitors were banned from the country, and soon afterward, conservation efforts in Uganda's national parks essentially halted. This lack of protection subjected Uganda's wildlife to heavy poaching, which decimated wild animal populations in its national parks, including those in MFNP.

An elephant with piapiac birds in Murchison Falls National Park.

By the end of Amin's regime in 1979, the situation in MFNP was critical, with elephant numbers reduced to an estimated 1 500 and hippos to 1 000. Buffalo and other large herbivores were reduced by 50% or more, and rhinos were nearly reduced to extinction. During the ensuing turbulence in the early 1980s, wildlife persecution continued unabated, and by 1984, wildlife in MFNP was almost gone, with estimated populations as follows: elephant 250, buffalo 900, kob 6 000, lion extinct, giraffe nearly extinct, rhino extinct.

After the ousting of the Obote regime in 1985, rule of law was restored in Uganda and national park protection was again enforced. The country re-opened for eco-tourism and wildlife numbers slowly began to recover.

Rothschild's giraffes and the Victoria Nile River in Murchison Falls NP.

A 2010 census of wildlife numbers in MFNP (including Bugungu and Karuma Wildlife Reserves) funded by CITES, revealed wildlife populations as follows: buffalo 9 200, Rothschild's giraffe 900, hippo 1 000, Ugandan kob 36 600, elephant 900, Defassa waterbuck 6 400, warthog, 2 000, Jackson's hartebeest 3 600. While these wildlife numbers are a far cry from the numbers in the 1960s, the data do show that the park's wild animal populations are indeed recovering.

Lion numbers in MFNP are healthy, with a population of 150 in some 15-20 prides. Other species often seen on game drives in MFNP include spotted hyena, leopard, side-striped jackal, Bohor reedbuck, bushbuck, oribi, olive baboon, vervet monkey, and the localized patas monkey. Forested regions in the south of the park and in Bugungu and Budongo provide good chances to see chimpanzee, black-and-white colobus, and several other species of monkey.

A buffalo luxuriates in a mud bath, Murchison Falls NP (Copyright © James Weis).

A 2015 biodiversity survey of MFNP (including Bugungu and Karuma Wildlife Reserves) conducted by Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) revealed a list of 144 mammal species, 556 bird species, 51 reptile species, and 51 amphibian species.

Birding in MFNP is very good, with plenty of the more common dryland species seen on both side of the river, as well harder to find 'specials' in the very productive forests in the south. There is a popular red-throated bee-eater colony that nests in the Nile River bank downstream from the Murchison Falls and the highly sought-after shoebill stork can sometimes be seen near the estuary of the Nile as it enters Lake Albert.

Red-throated bee-eaters nesting in the river bank in Murchison Falls NP.

Activities in MFNP

Game drives are the best way to experience wildlife in MFNP, especially on the northern side of the Nile River. The area near Paraa and the Victoria Nile delta is particularly good for game viewing. Lions are seen often in this section of the park, as are herds of buffalo, kob, and other plains game. The area south of the river is much less productive for game viewing, as the denser vegetation is less suitable for plains species.

Hippos in the Victoria Nile River, Murchison Falls National Park.

Nile River Boating

The boat excursion from Paraa to the base of the Murchison Falls is the most popular activity in MFNP. The waterfall cruises have been running since the 1950s (except when the park was closed in the 1970s), with several departures daily. Smaller boats seating around 5 passengers are available, as well as the 40-passenger double-decker boat, and mid-sized boats seating groups of up to 16 passengers. The round trip adventure takes around 3 hours.

Game viewing from the river on board the boat is usually superb, with lots of hippos, large crocodiles, buffalo, Defassa waterbuck, kob, and sometimes giraffe and bushbuck. Elephants are occasionally seen drinking on the banks or in the water swimming and playing. Birding from the boat is also excellent.

Boat excursion from Paraa looking towards the Murchison Falls.

Another boating option from Paraa is the Nile Delta Cruise, departing from Paraa and heading downstream towards Lake Albert. This scheduled excursion departs early morning and lasts 4-5 hours. Birding is exceptionally good, with a good chance of spotting the shoebill stork.

All Nile River boating trips may also be booked privately, as well as tailored towards special interests, such as birding or photography.

A lioness in Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda.

The Falls from Land

Visiting the Murchison Falls on foot is another very popular activity in MFNP. A road leads to a picnic site on the south bank of the Nile River, and from there, a short hike brings you to a spectacular viewpoint the the edge of the waterfall. The vantage point permits one to get a true feel for the power of the water as it rushes thru the narrow gap into the gorge.

A second walking path leads to another viewpoint that gives excellent views of both cataracts: the Uhuru Falls and Murchison Falls. A third pathway leads down to the bottom of the small gorge at the base of the main waterfall. Visiting all three viewpoints will take at least two hours. The afternoons are best for photographing the waterfalls.

Visitors view the impressive Murchison Falls (Copyright © James Weis).

Weather and When to Go

Like much of Uganda, MFNP's location near the equator means it enjoys a warm, tropical climate all year. This park is also uniformly lower in elevation (2 000-3 900 feet/615-1 190 meters) than the parks to its south, and it therefore experiences warmer temperatures than any other park in the country. Temperatures in MFNP are uniformly warm all year, averaging 86-90°F (30-32°C) during the day and only dropping to 62-66°F (17-19°C) overnight.

MFNP experiences a short dry season that runs from December thru February, when rainfall is uncommon (though still possible) and the days can be stiflingly hot. The lack of humidity does moderate the feel of the heat somewhat.

The Murchison waterfall as it flows through a narrow opening in the rocks (Copyright © James Weis).

The wetter season runs from March thru November, although the region is comparatively dry and does not receive a large amount of rain (average annual rainfall is only around 40 inches (1 000 mm). The rainiest months are April/May and August thru mid-October. Heavy storms are possible.

As in most savanna ecosystems, game drives are most productive during the dry season, especially along the Nile River, where herds of elephant, buffalo, and kob congregate to drink. Scenically, the wet season is spectacularly beautiful, and the the slightly lower rainfall in June/July make this period a great time to visit.

The diminutive oribi can be seen in Murchison Falls NP.

How to Get There

MFNP is reachable by road from Kampala in 4-5 hours and from Fort Portal (if on a circuit traveling from the southwestern parks) in around six hours. Scheduled and charter flights are available from Kampala/Entebbe and from all of Uganda's other protected areas, including from the remote Kidepo Valley.

The ferry crosses the Nile River near Paraa in Murchison Falls NP (Copyright © James Weis).

Mgahinga Gorilla National Park

Uganda's smallest national park is Mgahinga Gorilla National Park (MGNP), which covers a mere 15 square miles (38 sq kms) and forms a portion of the much larger trans-frontier area protecting the Virunga Mountains.

The Virungas are volcanic mountains that straddle the shared borders between Uganda, Rwanda, and the DRC and are afforded protection via three contiguous national parks (MGNP in Uganda, Virunga NP in the DRC, and Volcanoes NP in Rwanda).

View from Lake Mutanda to Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, showing the volcanic peaks of Muhabura (left) and Gahinga (right).

Mgahinga was originally established by the British Colonial Administration in 1930 as the Gorilla Game Sanctuary, but it only received national park status much later, in 1991. The new national park status resulted in the forced eviction of over 2 000 Batwa people, who had lived in the forests of the Virungas for centuries.

MGNP protects portions of three volcanic peaks: Gahinga (11 398ft/3 474m; shared with Rwanda), Muhabura (13 540ft/4 127m; shared with Rwanda), and Sabyinyo (12 037ft/3 669m; shared with Rwanda and the DRC).

A golden monkey seen in Mgahinga Gorilla National Park.

Gorilla Trekking

Guided hikes to visit habituated family groups of the endangered mountain gorilla are the main attraction in the Virunga Mountains and Mgahinga National Park. The 'gorilla trek' experience is unlike anything else in Africa and although most gorilla treks in Uganda take place in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Mgahinga also offers this amazing experience.

Mountain gorilla tourism became very popular after the release of Gorillas in the Mist, a 1988 major motion picture adaptation of the autobiography of Dian Fossey. Fossey lived and worked with the mountain gorillas for 18 years in the Rwandan section of the Virungas (Volcanoes National Park). Fossey's book and the movie brought global attention to the plight of these great apes, which share over 98% of the human genetic code.

Mgahinga Gorilla National Park protects part of the Virunga Mountains, which is home to one-half of the world's mountain gorillas (Copyright © James Weis).

Mgahinga's small size has meant that Bwindi, and to a larger extent Rwanda, have become the main destinations for mountain gorilla tourism. There has historically been only one habituated gorilla group in Mgahinga, while Bwindi and Volcanoes National Park (Rwanda) each have over ten habituated groups. Moreover, Mgahinga's gorilla group, known as the 'Nyakagezi group' sometimes crosses over into Rwanda, which means that trekking in Mgahinga is not possible until the gorillas cross back into Uganda.

A female mountain gorilla holds her youngster in the Virunga Mountains (Copyright © James Weis).

Other Activities

Besides gorilla trekking, MGNP offers a guided forest hike to visit Garama Cave. The cave was used by early humans during the late Iron Age, and later by the forest-dwelling, hunter-gatherer Batwa people. The cave can be explored for around 330 feet (100 meters). The Garama hike takes around 3 hours round-trip.

Other activities in MGNP include guided day hikes to any of the three volcanic peaks. A level of physical fitness is required for these mountain treks and each will take the better part of a day to complete.

Mountain hikes are available in Mgahinga NP - here a view to Mount Gahinga.

The Gahinga hike is the least challenging, taking roughly 6-7 hours, while Sabinyo takes a minimum of 8 hours, and Muhabura at least 9 hours. All three ascents offer incredible views and pass through interesting montane habitats, offering chances to see elephant, duiker, and bushbuck, as well as birds in the incredible Afro-montane and moorland habitats.

Treks to see and photograph the beautiful golden monkeys are offered daily in MGNP. Golden monkeys live in the lower-elevation bamboo forests in large troops and are typically encountered feeding up in the trees, rather than on the ground.

Cultural visits to a Batwa community, which may also include a visit to Garama Cave, are available on request.

The highest peak on Mount Sabyinyo, an extinct volcano shared by Uganda, Rwanda, and DRC.

Wildlife

Besides the mountain gorillas, MGNP is home to the golden monkey (Cercopithecus kandti), an endangered primate that lives in the bamboo forests of the Albertine Rift Mountains, (which includes the Virungas). Other species in the park include black-and-white colobus, bushbuck, buffalo, black-fronted duiker, elephant (rarely encountered), bush pig, giant forest hog, and various bats, rodents, and small predators.

Weather and When to Go

Rain can fall on the forested slopes of the Virungas Mountains at any time throughout the year, so bringing rain gear is essential for any hiking in the park. Gorilla trekking in MGNP is available year-round (provided that the gorilla group is spending time in the park and hasn't crossed into Rwanda), but the short dry season from June thru August provides the best chances for a rain-free experience.

The regionally endemic golden monkey can be seen in the bamboo forests of Mgahinga NP.

The montane climate in MGNP is defined by regular rainfall throughout much of the year, with misty and chilly air common in the upper elevations of the volcanoes. Air temps are relatively constant through the year, with daytimes averaging 58-63°F (14-17°C) and dropping to 40-45°F (4-7°C) overnight.

Temperatures will drop as you ascend to higher elevations, and sudden weather changes, including rain and cloud cover, are common and impact the temperatures. Dressing in layers is crucial to moderate your body temp. Please read our Gorilla Trekking Clothing and Gear section on the Bwindi Details tab for info on what to bring.

Unusual moorland vegetation in the high elevations of Mgahinga Gorilla NP.

How to Get There

MGNP is located only 8 miles from the small town of Kisoro, but the road to the park is slow going, so allow an hour to reach the park. Most visitors to MGNP will arrive via road from one of the Ugandan parks to the north, including Bwindi (~2 hours) or Queen Elizabeth (~6 hours). Flights to Kisoro from Kampala/Entebbe take about 90 minutes, and although driving from Entebbe/Kampala is possible, it will take around 9 hours.

A juvenile mountain gorilla under the watchful eye of the "silverback" (Copyright © James Weis).

Semuliki National Park & Semliki Wildlife Reserve

The Semliki River, which drains Lake Edward north into Lake Albert, gives its name to two of Uganda's most extraordinary protected areas: Semuliki National Park and the Semliki Wildlife Reserve (formerly the Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve). The lower reaches of the Semliki River form part of the international border between Uganda and the DRC, as it flows through a valley at the base of the Albertine Rift.

The low-lying tropical rainforest of Semuliki National Park is located along the river and country border, while the savanna-based Semliki Wildlife Reserve lies just to the east, with the northern foothills of the Rwenzori Mountains separating the two protected areas.

The grey-cheeked mangabey is one of over 50 mammal species found in Semuliki NP.

Semuliki National Park

Semuliki National Park (SNP) was first given protection as a forest reserve by the British Colonial Administration in 1932 (then known as the Bwamba Forest Reserve). It remained a forest reserve until 1993, when it was declared a national park. SNP is an extension of the DRC's Ituri Rainforest, which covers a massive 24 300 square miles (63 000 sq kms) of mostly unspoiled lowland forest that extends from the Uganda border all the way west to the Congo River Basin. This forest, including SNP, is considered one of the richest areas of floral and faunal diversity in all of Africa.

Semuliki NP covers 85 square miles (220 sq kms) of rainforest at elevations ranging from 2 200-2 490 feet (670-760 meters). It is a true rainforest, receiving an average annual rainfall of around 50 inches (1 270mm), which peaks from March thru May and again from September thru December.

Semuliki is predominantly lowland tropical rain forest.

Semuliki is home to an astounding diversity of birds, with 441 species recorded to date (40% of Uganda's total species), including 216 true forest species (66% of Uganda's forest species) and numerous "tough-to-see" specials associated with the Congo Basin. SNP's bird list includes some 50 species found nowhere else in Uganda. In essence, SNP is a birder's paradise. Besides birds, the park has a list of over 450 known species (and counting) of butterfly, including over 50 species of forest swallowtails.

The park is also home to 53 species of mammal, including buffalo, leopard, hippo, elephant, African civet, bush pig, sitatunga, pygmy antelope, eleven species of primate, nine species of duiker, and an assortment of smaller species, including various squirrels and bats. Primates in SNP include chimpanzee, red-tailed monkey, vervet monkey, blue monkey, grey-cheeked mangabey, black-and-white colobus, olive baboon, Dent's mona monkey, De Brazza's monkey, and two nocturnal primates - potto and bushbaby (galago).

A black-and-white-casqued hornbill in Semuliki National Park.

One mammal species of note found in SNP is the water chevrotain (also called mouse deer), a tiny nocturnal ungulate similar to a duiker, that is associated with permanent streams or rivers. Crocodiles and hippos are found in good numbers in the Semliki River.

Activities in SNP center around forest walks, but one interesting attraction is a collection of natural hot springs at a mineral-encrusted swamp called Sempaya. The site attracts a large number of shorebirds and provides a natural salt lick for forest mammals. Cultural visits to a local Batwa pygmy village can be arranged.

Sempaya swamp's hot springs attract myriad wildlife.

Semliki Wildlife Reserve

First protected in 1929 and situated just to the east of Semuliki National Park, Semliki Wildlife Reserve (SWR) occupies 209 square miles (542 sq kms) of the Albertine Rift Valley floor between Lake Albert and the Rwenzori Mountains. The nearest town is Fort Portal, which is 6 miles (10 kms) south of the the reserve (but 20 miles/32 kms driving distance).

To the west of SWR is the western rift escarpment and the vast rainforests of the Congo Basin (of which Semuliki National Park is a part), which is mainly located across the Semliki River in the DRC. The steep eastern slopes of the valley, which are located inside the reserve, rise up 6 200 feet (1 900 meters) and are home to SWR's chimpanzees.

Hill landscape in Semliki Wildlife Reserve.

Most of SWR consists savanna grasslands on the Rift Valley floor, with elevations between 2 000-2 950 feet (620-900 meters). Portions of the reserve are quite different though, with steep hills and valleys. Southwest of SWR are the northernmost peaks of the Rwenzori Mountains, which continue southward for 75 miles (120 kms). The northern boundary of SWR is Lake Albert, the northernmost of the Great Rift Lakes.

A 1969 wildlife census of SWR revealed some of the highest plains game densities in the country, with nearly 20 000 Ugandan Kob, 650 Jackson's hartebeest, over 500 Defassa waterbuck, 700 buffalo, and healthy populations of elephant, lion, leopard, hippo, reedbuck, warthog, and more. Unfortunately, as with all of Uganda's protected areas, SWR was adversely impacted by the effects of war and neglect during the country's turbulent 1970s and 1980s and wildlife was decimated by poaching.

Boating is offered seasonally at Semliki Safari Lodge (image: Copyright © Semliki Safari Lodge).

It wasn't until after the opening of Semliki Safari Lodge in 1997, that wildlife numbers in the reserve slowly began to recover. Today, SWR is carefully managed and protected and wildlife have recovered dramatically, although not to levels seen in the 1960s. Jackson's hartebeest were eliminated completely, but other species populations have stabilized or are increasing.

The center portion of SWR is dominated by an ecosystem of grasslands, acacia/combretum woodland, and stands of borassus palms, which supports herds of kob, buffalo, elephant, reedbuck, and warthog. Lions and spotted hyenas are sometimes seen. The riparian forests in the east support waterbuck, bushbuck, warthog, duiker, giant forest hog, bush pig, forest elephant and various primate species. Hippo and crocodile are found in the far north, along the Lake Albert shore.

The strange-looking shoebill stork can be found in Semliki Reserve's far north, on its boundary with Lake Albert.

Other species sometimes seen include banded mongoose, civet, and pangolin. SWR's primates include chimpanzee, red-tail monkey, blue monkey, vervet monkey, black-and-white colobus, olive baboon, two species of galago (bushbaby), and potto. There is an ongoing chimpanzee research project conducted by the University of Indiana in SWR.

The reserve also boasts an impressive bird list, with over 450 species recorded. The much sought-after shoebill stork can sometimes be found in the marshes at Lake Albert.

Activities in SWR include game drives on the savanna plains, primate walks to see chimpanzees and the various monkey species, nature walks, and boat rides on Lake Albert to see hippos, crocs, and water birds.

Black-and-white colobus are one of Semliki's numerous primate species.

Weather and When to Go

The Semliki region has a hot, tropical climate, with consistent temperatures all year that average 84-90°F (29-32°C) during the day and 62-70°F (17-21°C) overnight. In terms of rain, it can occur any time in the rainforest of the national park, as well as in the wildlife reserve and as such, there is no true wet or dry season. Given the consistent temperatures and unpredictable rain, Semliki can be visited at any time.

How to Get There

Semliki is accessed from Fort Portal, which has a small airstrip and is a reasonably short drive from both the national park and wildlife reserve. Reaching Fort Portal from Kampala takes 7-8 hours by road or 1.5 hours by air. Most visitors arrive on a circuit from other destinations in Western Uganda, which would mean a much shorter drive.

Grassland meets lowland rain forest in Semuliki.

Rwenzori Mountains National Park

The Rwenzori Mountains were created three million years ago by tectonic upheaval along the western branch (Albertine Rift) of the Great East African Rift. The uplift that created the Rwenzoris also segmented the great paleo-lake Obweruka into three smaller lake (Albert, Edward, and George).

The Rwenzori range traverses around 75 miles (120 kms) in a roughly north-south direction along the western border of Uganda and the DRC and is the highest range of mountains in Africa. The range consists of six massifs separated by deep gorges: Mount Stanley, Mount Soeke, Mount Baker, Mount Emin, Mount Gessi, and Mount Luigi di Savoia (all six peaks are in the top ten tallest in Africa).

View of the Rwenzori Mountains from a stream in the foothills.

The highest peaks in the Rwenzoris are Margherita (16 762ft/5 109m) and Alexandra (16 677ft/5 083m), the twin peaks on Mount Stanley. The only African peaks higher than Margherita are Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya, both of which are freestanding extinct volcanes and not part of a true mountain range.

The Rwenzoris are usually associated with the legendary "Montes Lunae" (Mountains of the Moon), which in ancient times were described as being the source of the Nile River, particularly by the Egyptian mathematician Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. While it is true that the Rwenzoris are the source of some of the Nile's waters, it is only a small percentage of the total.

Watching the sunrise in Rwenzori Mountains National Park.

The origins of Rwenzori Mountains National Park (RMNP) began in 1937, when the boundaries of a reserve were demarcated. In 1941, all terrain above 7 200 feet (2 200 meters) was officially designated as the Rwenzori Mountains Forest Reserve (RMFR). During Uganda's war with Tanzania (1978-79) and Civil War (1981-86), all of Uganda's protected areas suffered, including RMFR, as hunting and encroachment ran unchecked.

In 1989, the upper elevations of the reserve were gazetted as Rwenzori Mountains National Park (RMNP); Bwindi and Mgahinga were also declared national parks at this time. In 1991, the lower-elevation montane forests were added to the national park. RMNP was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994.

One of the crater lakes in the foothills of the Rwenzori Mountains.

Today, RMNP protects 385 square miles (996 sq kms) of steep and extremely rugged terrain covering the central and eastern side (Ugandan portion) of the Rwenzori range. The park is contiguous with Virunga National Park across the border in the DRC. Approximately 70% of the park's area is at altitudes above 8 200 feet (2 500 meters) and an additional 28% at altitudes between 6 500-8 200 feet (2 000-2 500 meters). The Rwenzori range contains 23 peaks above 14 750 feet (4,500 meters).

The range's three highest peaks, Mounts Stanley, Speke and Baker (the third, fourth, and fifth highest peaks in Africa), are permanently covered by snowfields and retreating glacial ice. The ice is shrinking with climate change and the remaining glacial ice is only around a quarter of what it was 100 years ago. The lower peaks (Emin, Gessi and Luigi di Savoia) also retain more or less permanent snowfields.

Spectacular scenery high in the Rwenzori Mountains.

Flora

The slopes of the Rwenzoris can be divided into five distinct altitudinal 'zones', each having its own flora, fauna, and microclimate. The Rwenzori zones are: Montane Forest, Bamboo Forest, Heath/Heather, Afro-Alpine Moorland, and Rock/Glacier.