Botswana

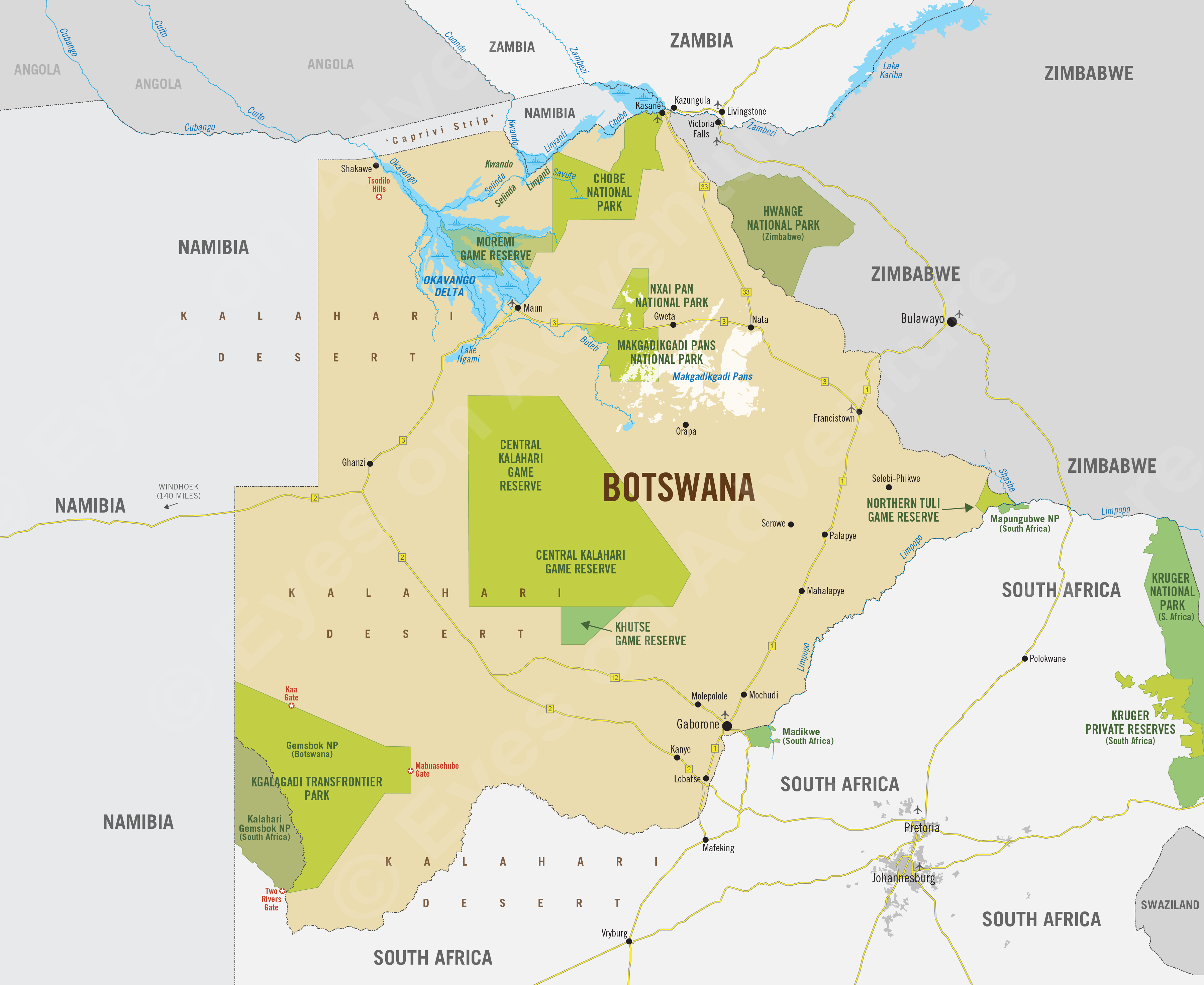

Region Links: Central Kalahari, Linyanti & Chobe, Makgadikgadi, Okavango Delta, Okavango Panhandle, Tuli Block

Highlights

- One of Africa's top safari destinations.

- The Okavango Delta is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a unique safari destination.

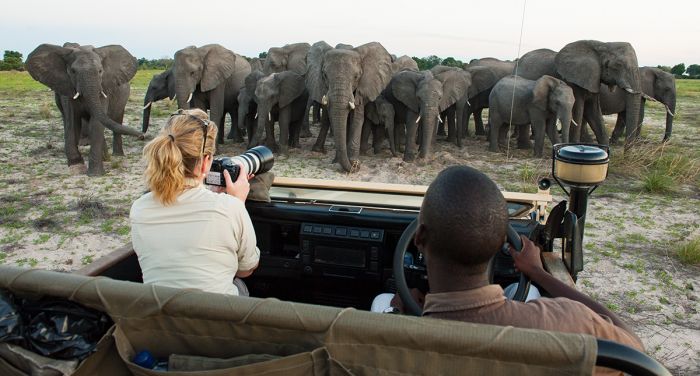

- The Chobe river for seasonally superb wildlife viewing from the water.

- Join adorable meerkats as they go about their day in the Makdagikgadi region.

- Go on a 'mekoro' (traditional canoe) excursion in the Okavango.

- Victoria Falls easily added to a northern Botswana safari itinerary.

Botswana is one of the world’s most beautiful and sparsely populated countries. In terms of safaris, it is undoubtedly one of Africa's premier destinations, with well-managed game reserves, plentiful wildlife, and some of Africa's last remaining wilderness.

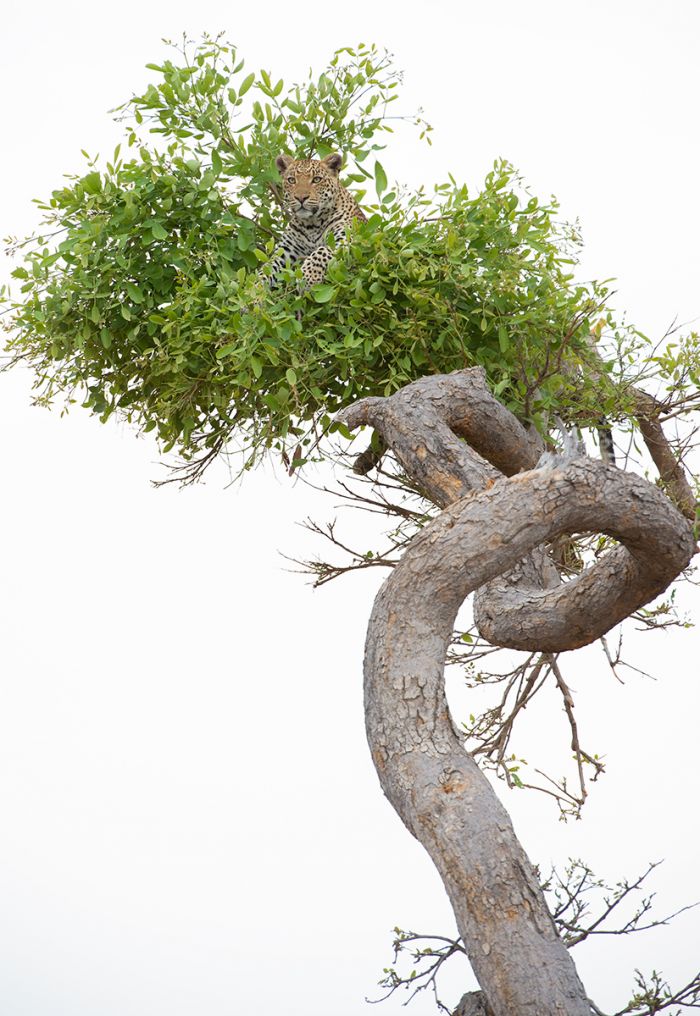

Young leopard in Botswana's Northern Tuli Game Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

The Okavango Delta is arguably the most unique and spectacular safari destination on the continent, with miles upon miles of wilderness, crystal clear waters flowing in a myriad and ever-changing network of rivers and islands, plentiful wildlife, and top-notch safari lodges.

Most of the country is flat and dominated by the spectacular Kalahari Desert. In fact, the Kalahari sands cover over two-thirds of Botswana. The Central Kalahari Game Reserve and the awe inspiring Makgadikgadi Salt Pans are two destinations in this dry, desert habitat, and both offer safari-goers a chance to marvel at the wildlife that thrives in this unforgiving ecosystem.

Lions crossing water in the Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

Along Botswana's northern border are the Chobe National Park and the Linyanti Reserve. Chobe is famous for its boating safaris on the Chobe river, with thousands of elephants and other wildlife that are sustained by this perennial waterway. The Linyanti a patchwork of private game reserves and offers a similar and spectacular experience to the Okavango Delta.

The lesser known Tuli Block is far removed from the northern wildlife reserves, bordering both Zimbabwe and South Africa in southeast Botswana. The Tuli region is gaining popularity, but still retains the feel and theme of most Botswana safaris, one of wilderness and wildlife.

Eyes on Adventure has a very special love for Botswana and we are eager to introduce travelers looking for the ultimate African safari to this exceptional destination.

White rhinos in Moremi Game Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Botswana Regions

Okavango Delta (incl. Moremi Game Reserve, Maun)

Botswana's premier wildlife destination offers one of the finest safari experiences in Africa. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this vast wetland is a pristine wilderness, packed full of plentiful wildlife with superb camps and lodges. More

Linyanti & Chobe (incl. Kwando, Selinda, Savuti Channel, Savute Marsh, Chobe River)

Bordering the Okavango Delta on the north, the Linyanti, Selinda and Kwando Reserves offer exclusivity in a pristine wilderness. East of the Okavango, Chobe National Park and the Chobe River offer land and water-based safaris. More

Makgadikgadi Pans (incl. Nxai Pan, Boteti River, Nata Sanctuary)

The incredible Makgadikgadi salt pans are a truly unique and unforgettable safari destination. The harsh environment is home to big herds of zebra the migrate seasonally between Nxai Pan and the Boteti River. See lions, meerkats and more! More

Central Kalahari (incl. Central Kalahari Game Reserve)

The Central Kalahari Game Reserve is one of Africa's great wilderness destinations with endless plains and fossilized rivers. See desert-adapted wildlife including cheetah, lion, herds of springbok, and more. Deception Valley is the setting for the best-selling book Cry of the Kalahari. More

Tuli Block (incl. Northern Tuli Game Reserve, Mashatu Game Reserve)

Bordering Zimbabwe and South Africa in the far southeast of Botswana, The Tuli Region offers a unique destination for Botswana safaris. The privately-owned, well-managed land offers superb game viewing with elephant, cheetah, lion, leopard and even horseback safaris. More

Okavango Panhandle (incl. Tsodilo Hills)

The Okavango River as it flows into Botswana and before it spreads out into the Okavango Delta, forms a region called the 'Panhandle'. Visitors can enjoy world-class fishing, endless beauty and solitude, and the historic Tsodilo Hills with its ancient rock art paintings. More

Read More...

Main: Flora, Geography, Important Areas, National Parks, Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, UNESCO Sites, Urban Areas, Wildlife

Detail: Chobe NP, Chobe Riverfront, Central Kalahari, Conservation, Francistown, Gaborone, Kasane, Kgalagadi, Khutse, Kwando, Linyanti, Makgadikgadi, Makgadikgadi Pans NP, Maun, Moremi, Nxai Pan, Okavango Delta, Okavango Panhandle, Savute Channel, Savute Marsh, Selinda, Tsodilo Hills, Tourism, Tuli Block

Admin: Travel Tips, Entry Requirements/Visas

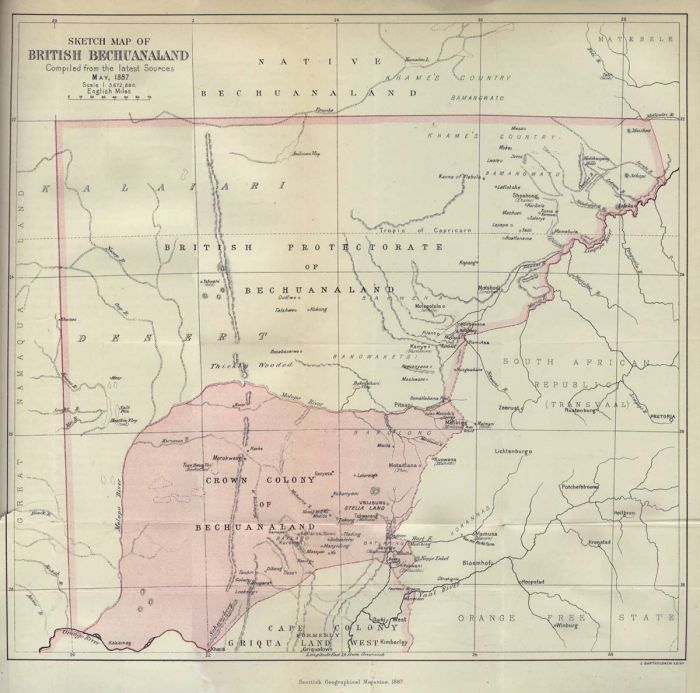

Geography

Botswana is located in the Southern Africa region and is completely landlocked. The majority of the country is covered by the Kalahari Desert, with a very flat topography and only occasional rocky outcrops that rarely exceed 100 meters in elevation. The country's two most notable features are the Okavango Delta, which is not a true delta (as it doesn't reach an ocean), and the massive salt pans of the Makgadikgadi.

A male lion in Botswana's Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

Botwana's lowest elevation point is in the extreme southeast, along its border with Zimbabwe and South Africa at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo Rivers, with an elevation of 1 683 feet (513 meters). The highest elevation point in Botswana is Monalanong Hill located just outside Gaborone, with an elevation of 4 902 feet (1 494 meters).

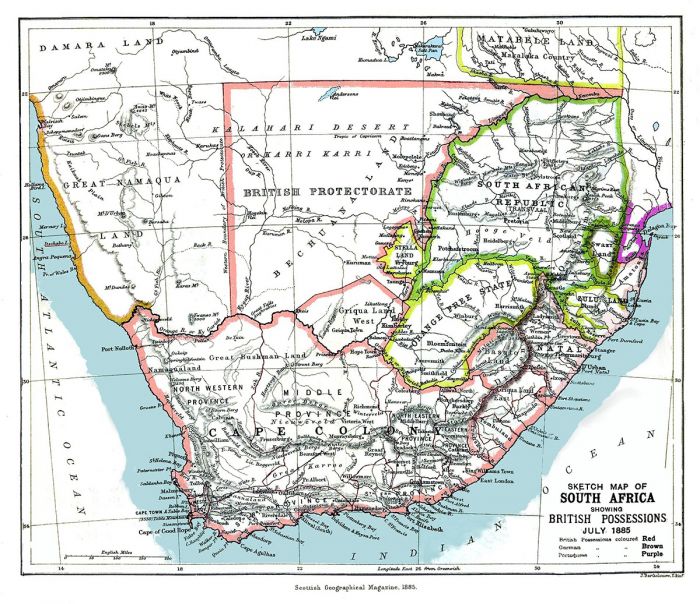

The country is bordered by South Africa to the south and east, Zimbabwe in the northeast, a tiny stretch of border with Zambia along the Zambezi River in the extreme north, Namibia's 'Caprivi Strip' in the north and Namibia in the west.

Most of Botswana's population and its only two notable cities, Gaborone (metro area: 400 000 people) and Francistown (metro area: 150 000 people), are situated along the southeast border of the country, where the land is less sandy and more suitable to agriculture.

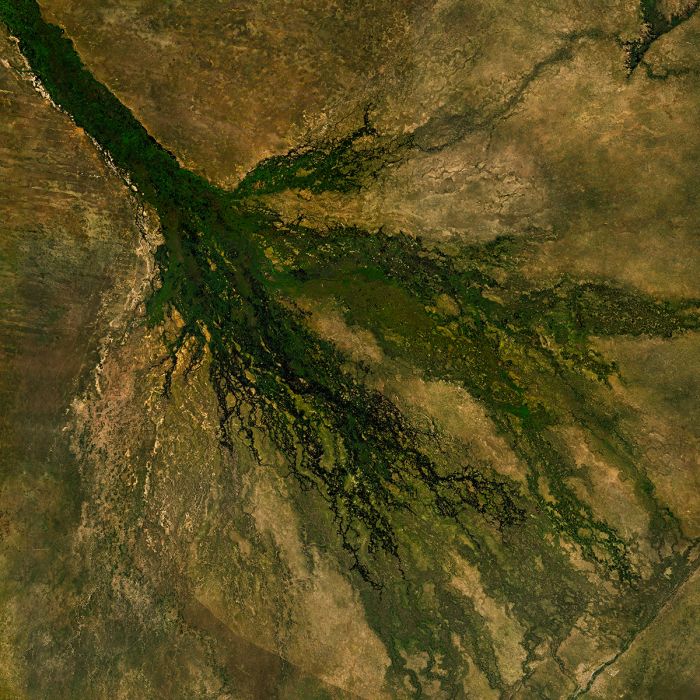

Aerial view above the Okavango Delta, showing the annual flood water covering the desert sand.

Northern Botswana (Geography)

Northern Botswana is the country's main safari region. The region is a paradise for wildlife and is utilized, in large part, for photographic safari tourism. Although divided and designated as distinct regions in northern Botswana, the Okavango Delta, Chobe National Park, and Linyanti / Selinda / Kwando wildlife reserves are in fact one contiguous environment, with abundant wildlife living and moving freely across these large ecosystems. This combination of open, uninterrupted, vast ecosystems explains why northern Botswana is such a spectacular destination for safaris.

Aside from the towns of Maun (at the southern boundary of the Okavango) and Kasane (on the northern border of Botswana), and a few small local villages scattered across the north, there are very few people living in the region. Northern Botswana is certainly one of the world's last great natural environments, where wildlife still mostly exists as it did many centuries ago.

Northern Botswana offers superb wildlife habitat and is one of Africa's best destinations for a safari.

The Okavango Delta (Geography)

The Okavango Delta is technically not a delta, but rather an 'alluvial fan', as a true delta is created by rivers reaching the sea, and the Okavango River empties into the Kalahari sands and never reaches the sea. It has the shape of a fan or delta when viewed from high above.

The Okavango River is sourced by two rivers to its north: the Cuito and the Cubango, which both have a catchment area in the highlands of Angola, far to the north. As the rivers reach the southern Angola border, they join and become the Okavango River, which flows south across the Caprivi Strip (Namibia) and into Botswana.

Flowing southeast into Botswana, the Okavango River spills into a shallow tectonic trough created between two fault lines running northeast and forming the northern and southern boundaries of the Okavango Delta, the southern fault running through the town of Maun. The trough is relatively flat and the water from the Okavango River spreads out as it fills the trough, creating the seasonally flooded Okavango Delta. The delta is situated at the far southern point of Africa's Great Rift.

Satellite image of the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

Makgadikgadi (Geography)

Prior to the formation of the Okavango trough, the Okavango River once flowed further southeast, where it is thought that it joined either the Limpopo River (which flows east into the Indian Ocean) or the Orange River (which flows west into the Atlantic Ocean).

Later, some time between two and five million years ago, an upliftment in Botswana's Kalahari Desert blocked the Okavango River and created a massive paleo-lake (Lake Makgadikgadi).

Lake Makgadikgadi eventually overflowed its banks around 20 000 years ago, creating a new river which flowed northeast and joined the Linyanti/Chobe River system, forming the middle Zambezi River. This water eventually eroded basalt rock as it flowed east, creating deep gorges and The Victoria Falls.

When the southern fault of the Okavango Delta began uplifting, the river's flow was further blocked and this began the formation of the Okavango Delta. Millions of years of water entering the lake and with no outlet, would have meant that the lake was quite brackish and as the river was cut off from reaching it, Lake Makgadikgadi eventually dried up, leaving behind the salt pans that exist today.

Grasslands at the edge of the salt pans in Makgadikgadi, Botswana.

Flora

Kalahari Sandveld

Most of Botswana (over 90 percent) is covered with the sand of the Kalahari Desert, but still supports a savanna biome of grassland and in some places, open woodland. This biome is called Kalahari Sandveld. Besides various species of grass which thrive atop the majority of this biome are trees and bushes, including those of the genera Acacia, Combtretum, and Terminalia.

Early morning view of the Kalahari Desert in Botswana's Gemsbok National Park.

Mopane

The second largest major biome in Botswana is the mopane (pronounced "mope-ON-eee") biome. Named for the mopane tree (Colophospermum mopane), which is the most common and widespread of all the trees in northern and northeast Botswana, this biome has a variety of deep Kalahari sand and in some place, alluvial soils.

Mopane trees can exist as cathedral forest in better soils, with a hight of up to 80 feet (25 meters) or, in less productive, low-nutrient sandy substrate, they often only grow into low shrubs, known as 'mopane scrub' or in the Setswana language, 'gumane'.

Compared to other local trees, mopane are quite tolerant of poorly-drained soils, particularly where there is a high clay content, so they dominate large swaths of the permanent dry areas of the Okavango and Linyanti, as well as the region further southeast surrounding the Makgadikadi Pans.

Many herbivores favor the mopane's leaves, which are very nutritious, and they attract browsers such as elephants, impala, kudu and giraffe. The leaves retain their nutritional value even after falling, and are eagerly eaten. The mopane worm, the caterpillar of the mopane moth (Gonimbrasia Selina), provides important protein to a variety of birds and is a sought-after delicacy for the local people.

A herd of impala feeding amongst mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane) in northern Botswana.

Miombo Woodland

The dominant biome across many parts of South-Central Africa, including much of nearby Zambia to the north, Botswana has only a relatively small area in the extreme northeast (in and around Chobe National Park). Miombo is characterized by large wooded areas, interspersed with smaller semi-open spaces supporting some trees and shrub thickets.

The dominant trees in miombo woodland are Brachystegia and Julbernardia species. These trees shed their leaves for a short time in the dry season to reduce water loss and produce fresh foliage just prior to the rainy season (around November in northern Botswana). The name 'miombo' comes from the Bemba (a tribe from northeastern Zambia) word for the Brachystegia tree.

Shallow, grassy depressions, sometimes referred to as a 'dambo' or in South Africa, as a 'vlei', are often associated with miombo woodland. Dambos are typically damp for much of the year and therefore support neither trees nor bushes, but are home to rich grasses, flowering plants, and herbs, making them popular with grazing animals.

Elephants walk along the edge of miombo woodland in Botswana's Chobe National Park.

Forest

In the seasonally flooded areas of of northern Botswana, there are smaller biomes that support moist evergreen forests on islands in the Okavango Delta and along the major waterways including the Kwando, Selinda, Savute, Linyanti, and Chobe Rivers.

The numerous islands in the Okavango support water-adapted trees including the lofty real fan palm (Hyphaene petersiana), wild date palm (Phoenix reclinata), several species of fig tree (Ficus), willows, waterberries, and others. Over time, salts leach up into these islands from the surrounding water, and only the salt-tolerant spiky Sporolobus grass can grow there once the salts become too plentiful in the sand.

Riparian forests along the major rivers of northern Botswana, as well as throughout the Okavango Delta, support evergreen and deciduous forests, with trees such as the African mangosteen (Garcinia livingstonei), baobab (Adansonia digitata), African ebony (Diospyros mespiliformis, also known as jackalberry), sausage tree (Kigali africana), raintree (Lonchocarpus capassa), marula (Sclerocarya birrea), leadwood (Combretum imberbe), and many others.

An aerial view of one of the many private airstrips in the Okavango Delta, showing forested patches amongst the grassland.

Seasonal Floodplain

Seasonally flooded grassland is another minor biome, found mainly in the Okavango Delta, but also along the Linyanti, Kwando, Chobe, and Zambezi Rivers in northern Botswana. These floodplains typically support only grasses and other ground cover, including some flowers, that can survive being submerged for part of the year.

The Okavango Delta also has areas of perennial swamp, supporting papyrus (Cyperus papyrus), common reed (Phragmites australis), waterlilies, and other aquatic vegetation.

To read more about regionally specific flora in Botswana, click on the protected area links below and/or the region links at the top of the page.

Seasonally flooded grassland on the edge of Botswana's Okavango Delta and dry woodland to the north.

Wildlife

Botswana offers some of the greatest wildlife destinations in all of Africa. The Okavango Delta (often referred to simply as 'the Delta') in particular, along with the reserves located directly to the north - Linyanti, Kwando, and Selinda, have very low tourist-to-land-area ratios in spectacular wilderness settings and are home to abundant and diverse wildlife.

Other regions in Botswana, such as the Central Kalahari, Makgadikgadi and Nxai Pans, and Gemsbok National Park, offer wildlife safaris in areas that are vastly different from the Okavango. Central and Southern Botswana receives far less rain than northern Botswana, so the wildlife densities are much lower, but still worth visiting.

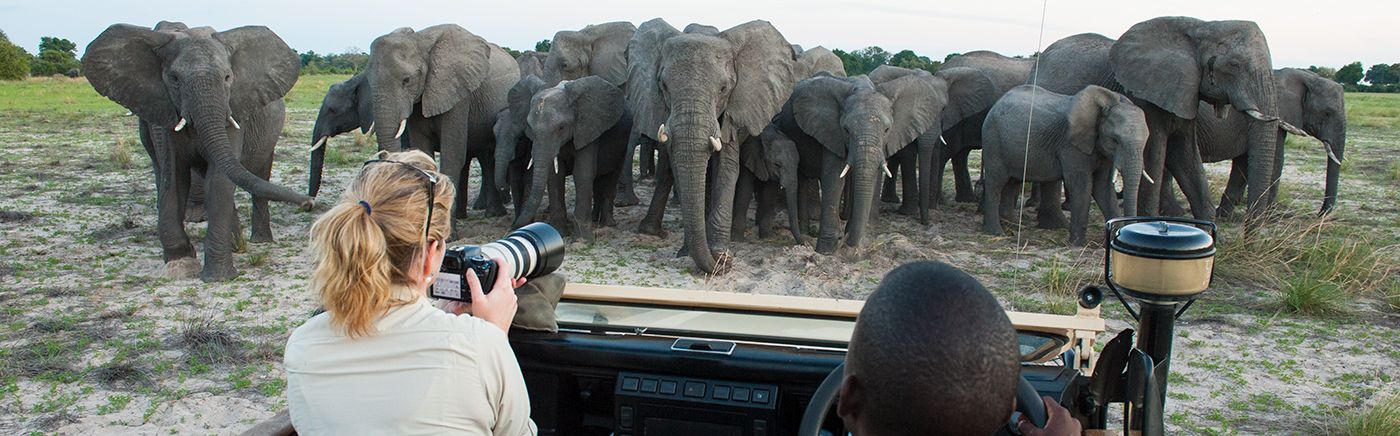

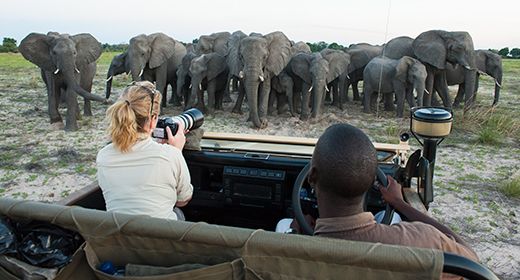

Elephants enjoying the rainy season in Botswana (Copyright © James Weis).

Northern Botswana (Wildlife)

Botswana's crown jewel of wildlife safaris is surely the Okavango Delta. The beauty of this wetland paradise, with blue waters, abundant wildlife, rich vegetation, and superb safari camps is without peer on the continent.

Wildlife in the Okavango includes all the iconic animals of Africa, including all of the Big Five - lion, leopard, elephant, buffalo, and rhino. Besides lion and leopard, large predators in the Okavango include cheetah, African wild dog, and spotted hyena. Smaller predators include two species of jackal, caracal, African wild cat, numerous species of mongoose, honey badger, and others.

Leopards are common throughout northern Botswana. Here one scans the plains from the top of a rain tree (Lonchocarpus capassa) in the Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

Plains game includes giraffe, Burchell's zebra, impala, blue wildebeest, greater kudu, common reedbuck, tsessebe, waterbuck, and warthog. The abundance of water in the Delta means that it is home to water-adapted species such as sitatunga and red lechwe. Bushbuck are common in the forested areas and are often seen in and around safari camps. Hippo and crocodile are here in large numbers in the deeper waterways. Primates include chacma baboon and vervet monkey.

Birding in the Okavango is outstanding, with a diverse mix of water birds and dryland species. The best months for birding are in the Spring (November thru March), when untold numbers of migrant species arrive from Europe and other Palearctic areas to breed.

To the north of the Okavango is a drier regio known as the Greater Linyanti. Most of the same species found in the Okavango also exist in this area, although the water-adapted species are restricted to the smaller sections along the rivers and in the Linyanti Swamp. Roan and sable antelope are both found in these areas north of the Delta.

The shy and water-adapted sitatunga is never found far from water, where it is able to stay safe from predation. Botswana's Okavango Delta is one of the best places in Africa to see these elusive antelopes.

The Okavango Delta and the Greater Linyanti are two of the best places in Africa to see the highly endangered African wild dog. Rhinos, both black and white species, were essentially wiped out in Botswana and only relatively recently reintroduced in the Moremi Wildlife Reserve, which is part of the Okavango Delta.

Northeast of the Okavango is Chobe National Park. Chobe is mainly a dry region, but like most of Northern Botswana, receives decent rainfall during the rainy season (December thru March) and offers water-based wildlife viewing along the Chobe River. The Savute Marsh, which fills seasonally and sporadically over the years via the Savute Channel offers excellent wildlife viewing in the less visited southern part of the park.

The Chobe wildlife experience is different from the rest of northern Botswana in that self-driving and camping is permitted, whereas most of the Okavango (some camping available in the Moremi Game Reserve) and the other northern reserves are private and only accessible by guests staying in one of the private safari camps.

Buffalo and yellow-billed oxpecker in the Linyanti Reserve in northern Botswana (Copyright © James Weis).

Chobe's best wildlife viewing is along the Chobe River, with boating safaris a specialty where one can observe wildlife in and along the river from the water. Excellent sightings of hippo, elephant, buffalo, crocodile, and red lechwe are a near guarantee during the driest months (July-October), as well as good chances of seeing other plains game and even lion, wild dog, or other predators.

Birding along the Chobe River is also outstanding, with lots of raptors like African fish-eagle, tawny eagle, snake eagles and more. Water birds are abundant, with many species of heron, egret, bee-eater, and plenty more. Boating on the river provides for up-close views of many birds not otherwise easily approached on land.

A boating safari on the Chobe River allows up-close views of wildlife, like this Nile crocodile (Copyright © James Weis).

Central Kalahari (Wildlife)

The Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) offers a distinctly different environment from the more lush northern reserves of Botswana. The CKGR is an arid region with less diverse wildlife that is more spread out due to the shortage of water for most of the year. The reserve has two pumped waterholes to help sustain the animals during the long dry months between May and October.

The best game viewing is during the rainy period from mid-December thru April, when large numbers of springbok, which are the most common large mammal in the reserve, congregate on the plains in the north of CKGR to enjoy the fresh short grass. Other large herbivores commonly seen in CKGR include blue wildebeest, oryx (gemsbok), red hartebeest, eland, and giraffe. Greater kudu are found in the reserve, but in small numbers.

The distinctive and desert-adapted oryx is a common resident of the Central Kalahari. A red hartebeest looks on in the rear (Copyright © James Weis).

Predators include leopard, lion, spotted hyena, and cheetah. Lions do not form big prides in CKGR, due to the sparse prey populations, and are usually encountered alone or in pairs. Cheetah do quite well in CKGR due to the wide open terrain that suits their hunting technique. Small numbers of lion, leopard, and spotted hyena, which always outcompete cheetahs in other areas where their numbers are greater, are also found in the reserve.

Other wildlife in CKGR include brown hyena, Cape fox, black-backed jackal, aardwolf, bat-eared fox, African wild cat, caracal, meerkat, genet, honey badger, and yellow mongoose.

Bird life in the reserve is restricted mainly to drylands species, such as ostrich, northern black korhaan, kori bustard, and various grassland birds. Raptors are quite common and include a variety of eagles, kites, Lanner falcon, and pale-chanting goshawk.

The arrival of the first rains is welcomed by the wildlife in the Central Kalahari of Botswana.

Makgadikgadi (Wildlife)

Although it at first appears a lifeless place and nothing lives atop the salt pans themselves, the Makgadikgadi region offers good wildlife, and seasonally, it offers superb wildlife.

The Boteti River, which forms the western boundary of Makgadikgadi National Park, is fringed with riparian vegetation and attracts herds of blue wildebeest and Burchell's zebra if the river has water (some years are dry and others the river flows).

Between June and December, herds of grazing mammals begin migrating from the north (Chobe and the Okavango) towards the Makgadikgadi to feed along the Boteti River's banks, which even in drier years, can sustain vegetation and enough water during these dry months. Besides the zebra and wildebeest, smaller numbers of eland, red hartebeest, and oryx (gemsbok) also arrive at the Boteti.

Zebras are seasonally abundant in Botswana's Makgadikgadi, particularly along the Boteti River.

When the first rains arrive (typically in November), the area around the Boteti is full of wildlife and the resident predators, including spotted hyena, lion, and black-backed jackal are here as well. Once the rains arrive in earnest (usually in late December), the herds disperse away from the Boteti to feed on the fresh grass that erupts across the Makgadikgadi plains surrounding the pans.

Nxai Pan in particular provers excellent grazing and becomes a great place for wildlife during the rainy months between December and April, but the Central and Eastern side of the Makgadikgadi is also excellent during this time.

Bull elephants arrive to drink at Nxai Pan in Botswana's Makgadikgadi region.

The area around Nxai Pan is also well known for attracting good numbers of springbok and impala, which in turn attract predators that favor them, including cheetah, leopard, and African wild dog. The Nxai Pan area is one of the few places where springbok and impala are commonly seen together.

The Makgadikgadi region is a very good place to see the uncommon and solitary brown hyena, which is resident here.

Another denizen of the Makgadikgadi is the enchanting meerkat (or suricate). These highly social mammals live in groups (or packs), spending their nights in excavated burrows and foraging for insects, scorpions, and other small animals during the day. Certain meerkat groups in the Makgadikgadi have become semi-habituated to seeing human visitors spending time with these animals is a very special experience for visitors.

Meerkats in the Makgadikgadi region (Copyright © James Weis).

Gemsbok National Park (Wildlife)

The remote and least visited of Botswana's national parks is Gemsbok National Park, which is part of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (KTP) that is shared by Botswana and South Africa. The South African side of KTP is the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park.

Gemsbok NP and the Kgalagadi TP are unfenced and open between the two countries. The park offers a self-drive safari experience with camping at designated campsites. The park is located in the Kalahari Desert and experiences a semi-desert climate; as such, the wildlife one can expect to see here is adapted to living in this rather harsh environment.

The names of both national parks come from one of the resident species found here, that of the gemsbok, which is a local name for the oryx. Oryx are found in the park in good numbers, as are springbok, eland, red hartebeest, and blue wildebeest, all of which are fairly common seasonally. Meerkats are another favorite species found in the park.

Springboks in Botswana's Gemsbok National Park.

Predators include lion, leopard, both brown and spotted hyena, cheetah, African wild dog (occasionally), black-backed jackal, and bat-eared fox. Male lions in this region have developed darker manes and are sometimes referred to as black-maned Kalahari lions. Cheetah are present in good numbers and are seen regularly.

Birders will also find KTP to be excellent, with vultures, eagles, bustards and ostrich all common. The birding list is around 250 species in KTP.

The best wildlife viewing in the Kagalgadi Park is from March thru May, which is the end of the rainy season.

A caracal walks along red Kalahari sand in Gemsbok National Park (part of Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park).

Tuli Block (Wildlife)

The small Tuli Block and Northern Tuli Game Reserve are located in the extreme southeast of Botswana, bordering Zimbabwe and South Africa. This small region is surely one of the country's best-kept safari secrets.

Wildlife in Tuli is superb, with a high diversity and abundance of animals and birds. The stars of the show in Tuli are certainly its resident population of elephant. It's hard to take a game drive without seeing them and they are quite relaxed and used to vehicles, so the experience is greatly enhanced by being able to see them at close quarters.

Besides elephant, other large mammals in the Tuli Block include eland, giraffe, Burchell's zebra, blue wildebeest, greater kudu, waterbuck, impala, warthog, bushbuck, klipspringer, and common duiker. Primates include vervet monkey and chacma baboon. Hippo and crocodile can sometimes be seen in the deeper parts of the Limpopo River.

A cheetah with her small cubs in Botswana's Tuli Block (Copyright © James Weis).

Predators commonly seen in Tuli include lion, cheetah, and leopard and a 3-day visit will give a very high probability of seeing all three of these cats. Other predators present in smaller numbers include spotted hyena, black-backed jackal, bat-eared fox, honey badger, serval, and African wild cat.

Birding in Tuli is excellent, with over 350 recorded. Ostrich are commonly seen, as is the huge kori bustard, the world's largest flying bird.

The Northern Tuli Game Reserve offers a superb wildlife experience (Copyright © James Weis).

Birds in Botswana

For hard-core birders or just the casual observer, Botswana offers an excellent birding experience and the country's diversity of avian fauna is an added bonus to any wildlife safari, regardless of one's degree of birding enthusiasm.

Seasonally, as is the case with neighboring South Africa, the best months for maximizing bird species is during the summer months between November and February, when resident populations are boosted by the numerous Palearctic migrant species that arrive from Europe, Asia, and North Africa to breed.

A carmine bee-eater with a mantid, photographed in northern Botswana's Linyanti Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Botswana has no endemic birds but the total checklist over 600 species, of which 169 are migratory. The Okavango is surely the best overall destination for total birds, with the abundant water habitat adding to the total species possible. Botswana has 12 Birdlife International Important Birding Areas (IBA's)

Most of the safari guides in Botswana's national parks and reserves are also adept birders, and one can expect to get 100 species in a day and maybe double that during the summer.

A southern white-faced owl (Ptilopsis granti) in Botswana.

CONSERVATION & TOURISM

The National Parks and Reserves in Botswana are a haven for wildlife and offer outstanding photographic safaris. Administratively, Botswana is divided into parcels of land called Wildlife Management Areas (commonly referred to as concessions).

Concessions in the Ngamiland District, which includes the Okavango Delta, Moremi Game Reserve, and Greater Linyanti reserves, are identified by codes beginning with 'NG' and numbered NG1 to NG51 (see map at top for details). The concessions are owned by the government and most are managed by local communities. Some of the concessions are leased to safari operators, who contstruct camps or lodges and market eco-tourism experiences to a global market.

Northern Botswana is one of the best places to see the endangered African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus). Here is one seen in the Okavango Delta.

Botswana has conserved 17% of its land as National Parks and Reserves and an additional 22% as protected Wildlife Management Areas (WMA's). This foresight, along with strong conservation policies and minimal population pressure, has given Botswana its unique position for exclusive eco-tourism.

Botswana's primary policy regarding tourism is a premier price, low volume strategy. The country has chosen not to overexploit its wildlife and wilderness resources with mass tourism, as has happened in some areas of East Africa. Botswana is committed to long-term gains, with an emphasis on uplifting its citizens through tourism and wildlife.

Botswana's National Parks and Game Reserves are set aside such that no one may live within their borders (the one exception being the traditional San people in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve). All visitors must pay an entrance fee to enter and the number of beds inside these parks and reserves is strictly limited.

Lions and buffalos in the Okavango Delta, Botswana.

Protected Areas

Botswana has protected roughly 17% of its land as national parks, reserves, and wildlife management areas. Read about the details of each below.

National Parks

Following are Botswana's four national parks (including one that is part of a Transfrontier Park). Additional information on each is included further below this list:

- Chobe National Park - Botswana's oldest national park offers great game viewing along the Chobe River during the dry season, especially from July thru October when animals congregate at the river. The Savute Marsh experiences its best game viewing during the rainy months.

- Gemsbok National Park - The Botswana portion of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, which is shared with South Africa.

- Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park - Shared park with South Africa, located in the Kalahari Desert on the border with Namibia. Good for predators and desert-adapted antelopes. Self-drive or visit on an organized tour.

- Makgadikgadi Pans National Park - Protects the western side of desert savanna and large salt pans. The pans are the remnants of Lake Makgadikgadi, which dried up 10 000 years ago.

- Nxai Pan National Park - Protects the northern extent of the Makgadikgadi Pans. Seasonally superb wildlife viewing from December-April, with large herds and good predators.

Kubu Island in Botswana's Makgadikgadi Pans.

Important Areas

Other important areas of note in Botswana include wildlife and nature reserves, wildlife management areas (also called concessions), and regions that are worth consideration when planning your trip.

- Central Kalahari Game Reserve - Massive desert landscape reserve in central Botswana offering seasonally good wildlife viewing during the green summer months.

- Chobe Riverfront - Seasonally superb wildlife viewing along the banks of the Chobe River in Chobe National Park. Boat-based safaris are the specialty during the dry season when big herds gather.

- Greater Linyanti Region - Prime wildlife region located directly north of the Okavango Delta. Includes three important reserves: Linyanti, Selinda, and Kwando.

- Khutse Game Reserve - Smaller adjoining reserve on the southern boundary of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, offering a similar semi-desert experience. Good, but low-density, wildlife viewing. Popular with locals visiting from Gaborone.

- Kwando Reserve - Private concession located north of the Okavango, offering a superb wildlife experience.

- Linyanti Reserve - Private concession located north of the Okavango, offering a superb wildlife experience.

- Makgadikgadi - Area with large salt pans that are remnants of a long-dried paleo-lake. Includes two national parks: Makgadikgadi and Nxai Pan.

- Moremi Game Reserve - Protects the central core and prime wildlife habitat of the Okavango Delta. Only a few safari camps and some camping areas permitted in this massive reserve. Excellent safari region due to decades of wildlife protection.

- Northern Tuli Game Reserve - Privately-owned land made up of land previously used for farming that has been converted into a wildlife and eco-tourism reserve. Located in the Tuli Block, which borders South Africa and Zimbabwe.

- Okavango Delta - Botswana's premier wildlife destination. A huge and spectacularly beautiful destination that is a wetland that exists atop Kalahari Desert sand. A paradise for wildlife with superb safari camps. Highly recommended.

- Okavango Panhandle - The long stretch of the Okavango River as it flows across the Kalahari Desert en route south to the main Okavango Delta. Basic lodges offer fishing, boating, and birding. Not a big game destination. Water-based safaris as they were 50 years ago.

- Savute Channel - Waterway connecting the Linyanti Swamp to the Savute Marsh. Flows sporadically and has had long, historical cycles of flowing and dryness.

- Savute Marsh - Seasonal marsh in southern Chobe National Park with good wildlife, permanent safari lodges, and overland camping sites.

- Selinda Reserve - Private concession located north of the Okavango, offering a superb wildlife experience.

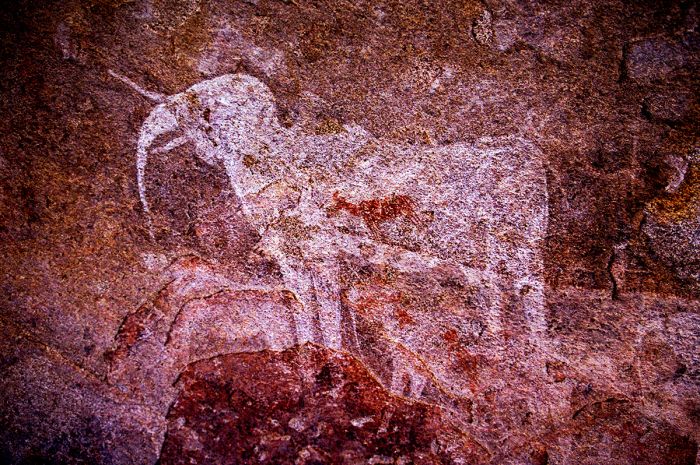

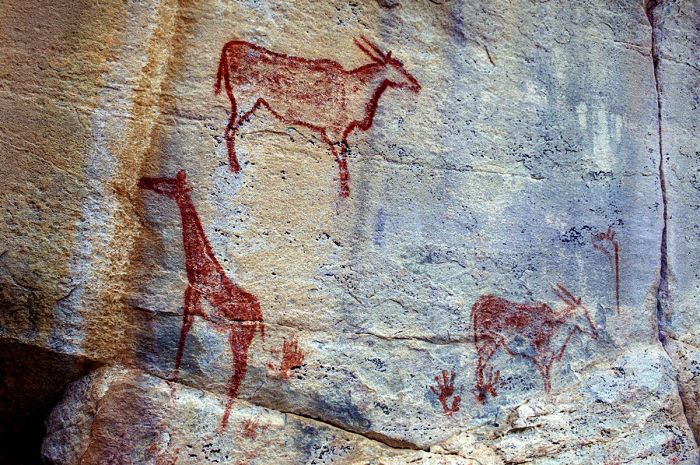

- Tsodilo Hills - A series of four hills rising in the otherwise flat Kalahari plains of northwest Botswana. The site has significant cultural value to the local San and Bantu people. Many examples of superb bushman rock art paintings. A UNESCO World Heritage Site open to tourists.

- Tuli Block - Located in far southeastern Botswana on the border with South Africa and Zimbabwe. Farmland converted to wildlife tourism with excellent safaris and few guests. Highly recommended.

Guests on safari in Botswana's Moremi Game Reserve with African wild dogs on the hunt (Copyright © James Weis).

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations whose mission is to promote world peace and security through international cooperation in education, the arts, the sciences, and culture. The Convention concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage was signed in November 1972 and ratified by the 189 UN member "states parties".

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area which is geographically and historically identifiable and has special cultural or physical significance. To be selected as a World Heritage Site, a nominated site must meet specific criteria and be judged to contain "cultural or natural heritage of outstanding value to humanity". An inscribed site is categorized as cultural, natural, or mixed (cultural and natural). As of 2021, there were over 1 100 sites across 167 countries.

Botswana has two UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- Okavango Delta (since 2014, Natural) - Inland delta (does not drain to a sea or ocean) system of permanent marshland and seasonally flooded plains. Home to some of the world's most endangered species of large mammal, including cheetah, rhino (both black and white species), African wild dog, lion, and others.

- Tsodilo Hills (since 2001, Cultural) - Site that has provided shelter to humans for over 100 000 years. Contains over 4 500 rock paintings of cultural significance dating from the Stone Age up to the 19th century. Revered as a place of worship for local communities.

The Okavango Delta is one of two UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Botswana. Hippos are found throughout the Okavango wherever there is deep enough water. This one has some yellow-billed oxpeckers hitching a ride (Copyright © James Weis).

Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. It was the first of the modern global nature conservation conventions, negotiated during the 1960s by countries and non-governmental organizations concerned about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for birds and other wildlife. The convention is named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, where the convention was signed in 1971.

Presently there are some 75 member States to the Ramsar Convention throughout the world which have designated over 2 300 wetland sites onto the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance.

Botswana has one site designated as a Wetland of International Importance (Ramsar Site) as follows.

- Okavango Delta - Combination of permanent and seasonal swamps, floodplains, and freshwater lakes that provides critical habitat for many species of birds and other wildlife. Home to over 1 000 species of flora, 650 species of bird, 32 species of large mammal, 68 species of fish, and a highly diverse insect population. Used for tourism, subsistence farming and fishing. (21 380 sq miles/55 374 sq kms)

The entirety of the Okavango Delta has been declared Ramsar Wetland of International Importance. Here a young male lion strides past some lucky safari guests in the Moremi Game Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Urban Areas

Botswana's urban areas are not destinations in their own right, but two of them - Maun and Kasane, are important hubs that serve the country's eco-tourism industry. Info on Botswana's most important urban areas follows below.

- Francistown - Botswana's second largest city, but below 100 000 residents. Located in the central-eastern part of the country near the border with Zimbabwe. Rarely visited by eco-tourists.

- Gaborone - Botswana's capital and largest city located in the far south of the country very close to the border with South Africa. The economic hub of Botswana. Rarely visited by eco-tourists.

- Kasane - Small town on the northern border of the country along the banks of the Chobe River. Visited by eco-tourists visiting Chobe National Park or en route to or from the Okavango Delta and Victoria Falls.

- Maun - The small and dusty gateway frontier town on the southern edge of the Okavango Delta. The most common entry point for air travelers heading to a safari in northern Botswana. The tourism capital of the country.

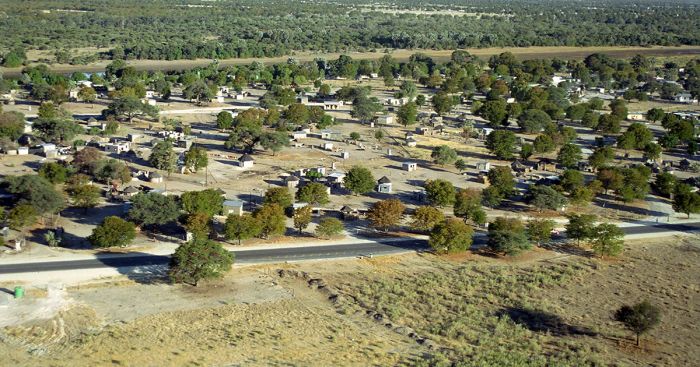

View over Maun, the small frontier town on the southern edge of Botswana's Okavango Delta.

Okavango Delta

Botswana's top wildlife destination is also one of the most incredible wildernesses left in Africa and on Earth. Formed by rivers that partially empty into a wide, but shallow trough between fault lines in the Kalahari Desert, the Okavango is not a true delta (since it does not exist at a river's exit to a sea), but its shape looks like a delta from far above, thus giving it this name.

Millenia of silted river water have turned the otherwise sterile Kalahari Desert sands of the Okavango Delta into a lush network of palm islands, woodlands, rich floodplain grasslands, papyrus-lined channels, and deep freshwater lagoons, that have become a haven for diverse wildlife.

The wildlife-rich Okavango Delta, with a channel in flow, flanked by riparian forest of palms, figs, and other trees and with seasonal floodplain/grassland beyond.

The Okavango is one of the last places in Africa where it can be said that the environment and most of its wildlife is little changed from hundreds of years ago, long before Europeans colonized the region.

Wildlife in the Okavango is diverse and abundant, with all of the Big Five (lion, leopard, elephant, buffalo and rhino) present, as well as all of Southern Africa's plains game and predators.

Black rhino were locally extinct in Botswana by the early 1990s, with only about a dozen white rhinos remaining in the wild. To save the last wild white rhinos in Botswana, the animals were captured and given safety in sanctuaries. In 2000, a rhino reintroduction program was initiated, and today, both species of rhino can be seen in the Okavango, albeit only in small numbers.

Animals that typically avoid water, such as lions, have adapted to living with the seasonal flooding of the Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

Herds of elephant roam freely in this large ecosystem, traversing the deep channels and feeding on abundant vegetation in the Delta's network of islands and waterways year-round. Buffalo are also quite abundant, forming herds in the hundreds in some places where rich grasslands are present.

Commonly seen plains game includes giraffe, Burchell's zebra, blue wildebeest, impala, greater kudu, tsessebe, waterbuck, common reedbuck, and warthog. The Okavango's abundance of water provide habitat for water-dependent antelopes like red lechwe and the shy and elusive sitatunga.

Common predators in the Okavango include lion, which are found in large prides in some areas of the Delta, leopard, spotted hyena, African wild dog, cheetah, black-backed jackal, serval, caracal, honey badger, and various species of mongoose.

Crocodile and hippo are abundant and seen throughout the Okavango, especially in the deeper lagoons and waterways. Primates in the Okavango include large numbers of both chacma baboon and vervet monkey.

Game drives in the Okavango are in open safari vehicles and frequently give visitors exceptional wildlife experiences (Copyright © James Weis).

Birding in the Okavango is outstanding, with a huge variety of both dryland and water species. Okavango 'specials' like the slaty egret, wattled crane, and Pel's fishing owl are just a few of the over 400 species that can be seen in the Delta. A typical day on safari in the Okavango can easily produce in excess of 100 species.

The Okavango has numerous safari camps for visitors, some are very high-end and luxurious, while others are more classic in style. None of the camps can be considered inexpensive. Most camps have accommodation for 10-24 guests and are physically distant from any other camps, such that guests will see few to no other tourists and have the feeling of being in a true wilderness.

Activities in the Okavango Delta include a mixture of game drives in open 4x4 vehicles and water-based activities (seasonally and depending on the specific camp) like motor boat outings and mokoro (dugout canoe) safaris.

Read full details on the Okavango and its safari camps and lodges here.

A mokoro safari is a must for all visitors who want to experience the traditional form of transport in the Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

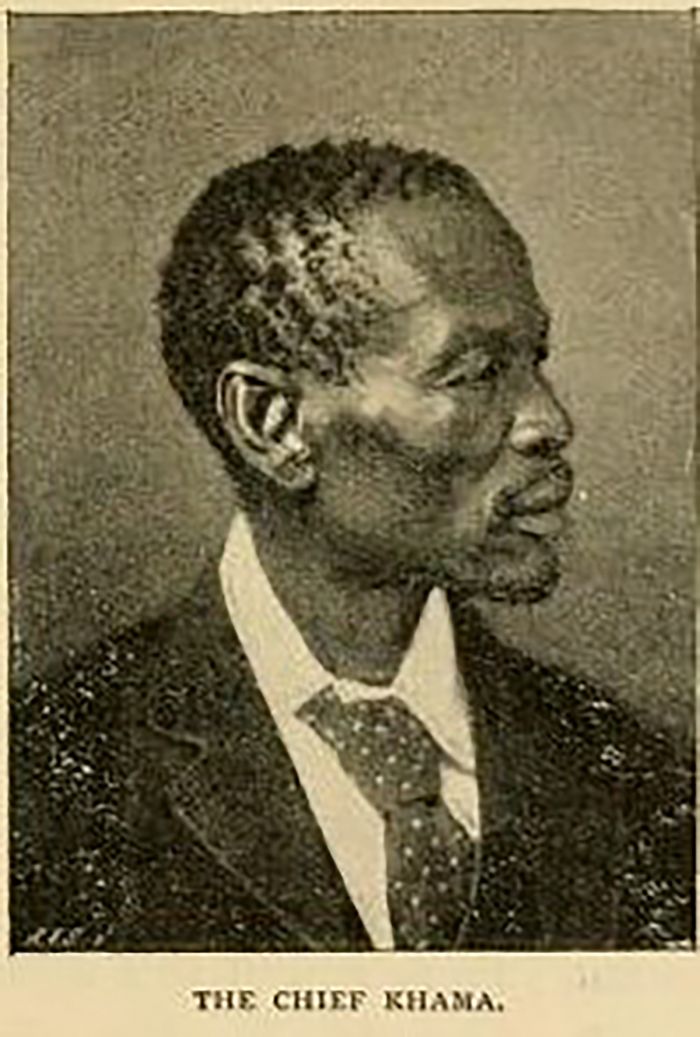

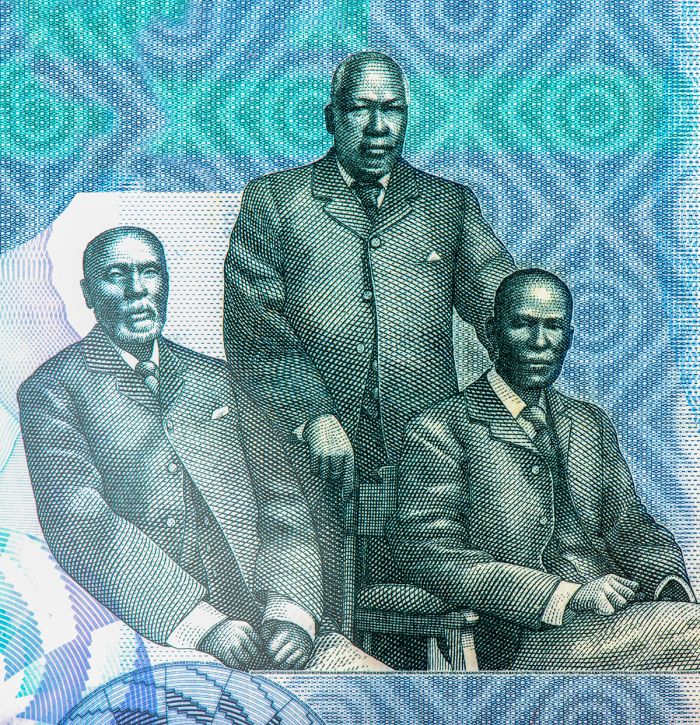

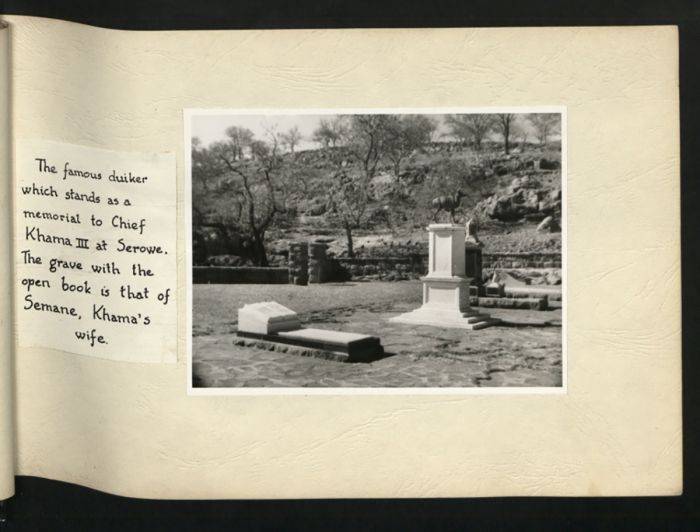

Moremi Game Reserve

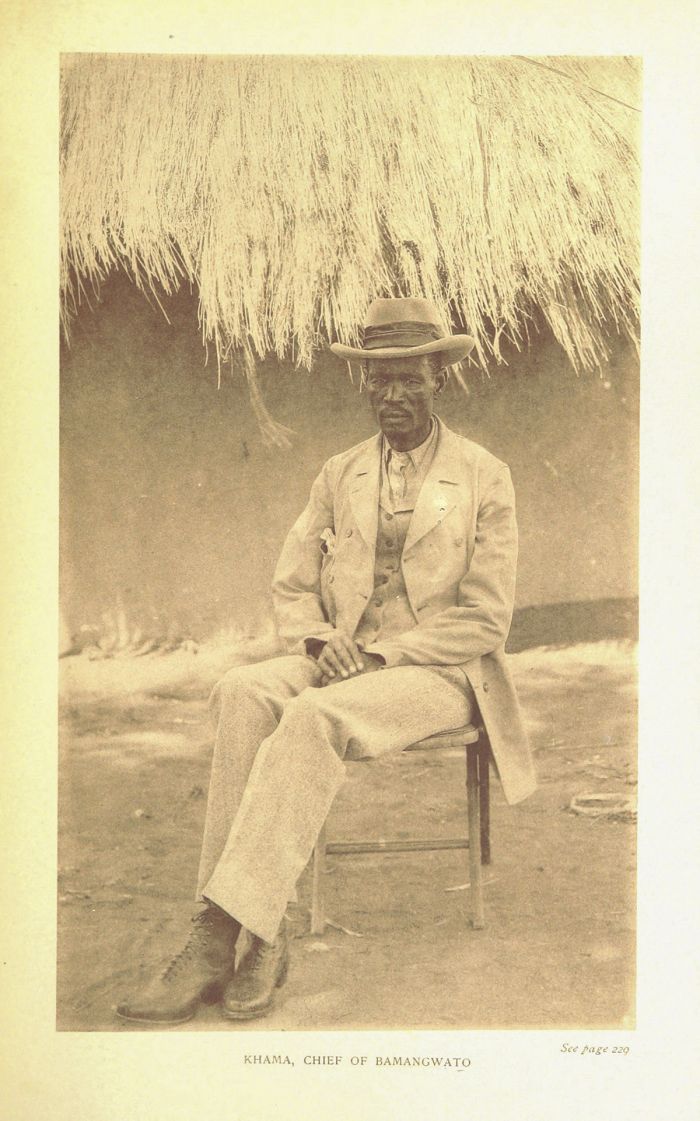

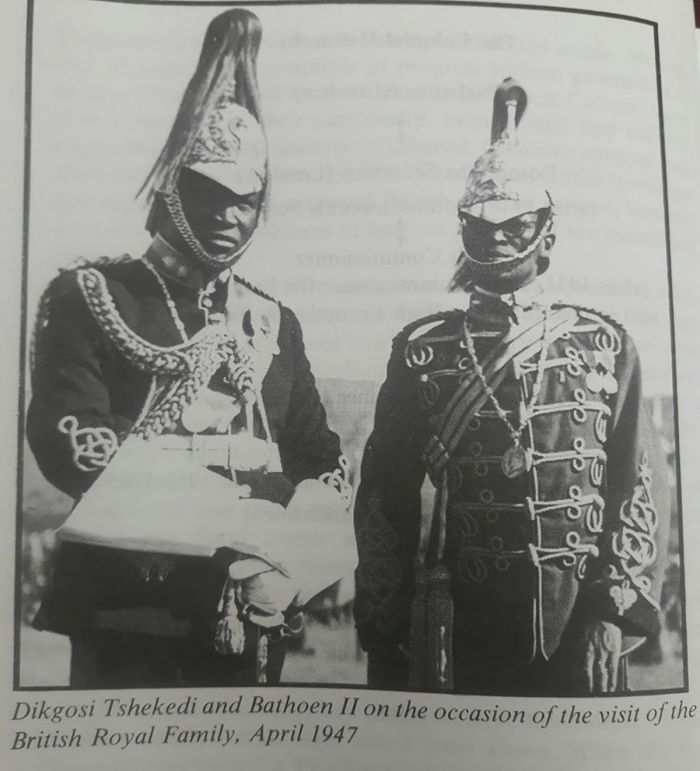

Established in 1963 to protect the core area of the Okavango Delta, the reserve was named for Chief Moremi III of the Batawana people. The chief was killed in a car accident in 1946 and his widow, Elizabeth Pulane Moremi, who was acting regent at the time, proclaimed the reserve in her husband's honor.

Moremi Game Reserve covers 1 881 square miles (4 871 sq km) of the central and eastern portion of the Okavango, including Chief's Island, the largest land mass in the Delta. The reserve occupies around one-third of the total area of the Okavango Delta. As the reserve has protected the core area of the Delta for over 50 years, the wildlife in Moremi has been relatively undisturbed by humans for many generations.

Cheetah are found in certain parts of the Okavango Delta, like this one seen in the Moremi Game Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Besides Chief's Island, Moremi protects vast areas of seasonal floodplains, permanently flooded shallows, deep lagoons and ever-changing papyrus-lined channels that are opened up by elephant and hippo. There area areas of savanna grassland, particularly on Chief's Island, mopane-tree and mixed-tree woodland, acacia scrub, riparian forest, numerous small, palm-fringed islands (most of which began as termite mounds), and permanent swamp.

Moremi offers arguably the best combination of wildlife and wilderness in all of Africa. Tourist densities in Moremi (and most of the Okavango outside Moremi) are some of the lowest of any of Africa's most popular wildlife destinations. The safari experience here cannot be overstated, it is pure magic and very difficult to beat.

As in much of the Okavango Delta, Moremi's wildlife is prolific and offers a dizzying variety of predators, plains game, big herds, water-dependent animals, and birds.

Red lechwe antelope are a water-dependent species that are found throughout the Okavango Delta and Moremi (Copyright © James Weis).

With the reintroduction of both black and white rhino on Chief's Island in the early 2000s, all of Africa's Big Five animals (lion, leopard, elephant, rhino, and buffalo) can be seen in Moremi.

Moremi has healthy populations of all the regional predators. Leopards are particularly abundant and the chances of seeing one on a safari are very good. Lions are present in good numbers and form prides of between 4 and 20 members, especially on Chief's Island. Spotted hyenas are also abundant and can be seen individually or in small groups, especially of there has been a kill. Cheetah are hit or miss in Moremi and the best chances of seeing them is on Chief's Island.

The endangered African wild dog is seen regularly in Moremi, though they are even more prevalent in the private reserves north of the Okavango (Linyanti, Selinda, and Kwando). The dogs' favored prey is the impala, which are present in huge numbers in Moremi.

The Okavango Delta and Moremi Reserve offer decent opportunities to see the endangered African wild dog. Here a pack cautiously stops to drink at the edge of water (Copyright © James Weis).

Other predators found in Moremi, as well as throughout the Okavango, include black-backed jackal, side-striped jackal, caracal (seldom seen), serval, bat-eared fox, African wild cat, honey badger, and various species of mongoose.

Common plains game in Moremi (and the Okavango Delta) includes elephant, impala, Burchell's zebra, giraffe, buffalo, greater kudu, waterbuck, tsessebe, warthog, blue wildebeest, and red lechwe. Other less frequently seen animals include sable antelope, bushbuck, common reedbuck, and roan antelope. Primates are restricted to chacma baboon, vervet monkey, and lesser bushbaby (galago).

Aardwolf, aardvark, and pangolin are found throughout the Okavango and Moremi, but are seldom seen. Hippo and crocodile are common in Moremi and all throughout the Okavango Delta in the deeper waterways and lagoons.

A male leopard seen on a safari in Botswana's Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

Birding in Moremi is fantastic, as it is throughout most of the Okavango, with a diverse mix of drylands species, waterbirds, and raptors. The bird life is abundant all year, but peaks when summer migratory species arrive en masse starting in September and leaving again around late March/early April.

Safari activities in Moremi include wildlife viewing via open 4x4 vehicles and boating / mokoro (dugout canoe) safaris at certain camps and dependent on water levels.

Read full details on the Okavango and Moremi and its safari camps and lodges here.

Nearing the end of the dry season in Moremi Game Reserve, this peaceful lagoon is a typical scene found throughout the Okavango Delta (Copyright © James Weis).

Okavango Panhandle

Viewed from far above, the Okavango River and Delta forms a shape that looks similar to that of a frying pan, the main area of the Delta waters spreading out in a roughly oval shape while to the northwest, the Okavango River that feeds the main delta forms a long diagonal 'handle'. The portion of the Okavango River from the northern Botswana border before its waters spread out into the delta itself, is known as the Okavango Panhandle.

Two parallel fault lines below the Kalahari sand have created steep banks that constrain the Okavango River from spreading out as it travels southeast towards the main Okavango Delta.

The two fault lines that flank the Okavango River in the Panhandle are situated roughly 6-9 miles (10-15 kms) apart. The river meanders between the steep banks, with frequent curves and the occasional lagoon, as it flows towards the main body of the Delta.

The main Okavango River in "the Panhandle", flowing south before it spreads out into the fan-shaped network of channels, swamps and islands that forms the Okavango Delta.

There are several villages with local people along the banks, including Shakawe, Sepopa, and Seronga, with subsistence farming and fishing being the main activities.

Safaris in the panhandle are quite different from those in the Okavango Delta. The camps are mostly low-key and offer a look back in time at what the entire safari industry of the Okavango was like some 50 years ago. The lodges and camps are very affordable compared to those in the Delta and far more basic in terms of amenities.

The Okavango River in the Panhandle is fringed in tall papyrus and reedbeds, with deep channels and some areas of sandy banks. Water lilies abound in the small lagoons, but the dominant vegetation is papyrus.

The African fish-eagle is found in the Panhandle and throughout northern Botswana.

The main activities for visitors to the camps in the Panhandle are boating (both motorized and mokoro - the traditional canoe propelled by a long pole), fishing, and birdwatching.

Wildlife in the Panhandle does not compare to that in the Delta, but there are antelope like sitatunga and red lechwe, plus an abundance of hippo and crocodile. If you're lucky, you may see the shy spotted-backed otter.

Birding in the panhandle, particularly for waterbirds, is superb. Common species include African fish-eagle, pygmy goose, African and lesser jacana, reed cormorant, darter, lesser gallinule, several species of bee-eater and kingfisher, herons, and egrets, and many more.

Read full details on the Okavango Panhandle and its safari camps and lodges here.

Shallow canoes called "mekoros" near the village of Seronga on the Okavango Panhandle. A mokoro is 'poled' through the water and is the traditional mode of transportation in the waterways of the Okavango (and still used today by locals). In days gone by, a mokoro was carved from wood, but today they are more eco-friendly and typically made from fiberglass.

Greater Linyanti Region

(including Selinda, Kwando, and Linyanti Reserves/Concessions)

Botswana's land is divided into tracts called Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs), which are more commonly referred to as 'Concessions' or sometimes 'Reserves'. The boundaries of these concessions are typically situated around a local community, which is given management of the land and its resources, including wildlife, subject to government restrictions.

Some of the concessions are 'leased' by the managing community to private interests, and in the case of the Okavango and areas to its north, the concessions are primarily leased (typically for a term of 15 years) to private safari companies, which build safari camps and operate wildlife safaris, with tourism revenue shared with the managing community.

Several decades ago, most of the concessions outside of the Moremi Game Reserve, which is fully protected, were leased to commercial hunting operators, but today hunting has mostly been pushed aside in favor of ecotourism.

The northern reserves (Linyanti, Selinda, Kwando) offer some of Africa's best elephant viewing opportunities. Here a breeding herd enters the Linyanti River (Copyright © James Weis).

Linyanti Geography & Habitats

The three most important ecotourism concessions outside of the Moremi Game Reserve are those in the 'Greater Linyanti', which include three Wildlife Management Areas (or Concessions): Kwando, Linyanti, and Selinda. Each of these private concessions are leased to a safari operator and offer an exclusive wildlife and nature experience for guests staying at one of the safari camps located inside these concessions.

The three concessions border one another but are not separated from one another by fences. The Selinda Concession is named for the Selinda Spillway, which connects to the Okavango Delta (some years flowing and some years mostly dry), while the Kwando and Linyanti Concessions are named for the perennial rivers of the same names.

The reserves are similar in terms of overall habitat, with areas of floodplain, grassland, riparian forest, and open woodland. There are significant areas of low shrub mopane and Kalahari apple-leaf, both of which are kept in check by the steady browsing of elephants, which relish the green leaves of both. There are also some smaller areas of well established cathedral mopane-tree forest.

Open game drive vehicles and very low tourist numbers make the Greater Linyanti region one of the best safari regions in all of Africa (Copyright © James Weis).

All three of these concessions are situated around the Linyanti Swamp, which consists of a large area of river channels, reedbeds, and papyrus marshes, created by the Kwando River as it flows south along the border between Botswana and Namibia. The water fills a shallow trough, creating the Linyanti Swamp and then continues eastward as the Linyanti River (which eventually joins with the Zambezi River as it heads to Victoria Falls).

During years of higher water in the Kwando River (which is sourced in the highlands of Angola), some water may overflow the Linyanti Swamp in flow into either or both of two additional channels: the Selinda Spillway, which flows westward toward the main Okavango Delta, and the Savute Channel, which flows eastward and can reach all the way to the Savute Marsh in Chobe National Park. Tectonic movements beneath the deep sand substrate in this region also affect the on-again, off-again flow of these two channels.

The Savute Channel fills with water some years and is dry in others. During a recent wet cycle, animals like these two male cheetah had to cross water to hunt their territory (Copyright © James Weis).

Savute Channel

The Savute Channel has experienced long cycles (sometimes decades) of alternating wet and dry periods. The area of the channel itself becomes a rich grassland during the channel's dry periods, attracting cheetah and herds of herbivores. The well documented 'drying up' of the Savute Channel in the 1980s, saw many thousands of animals, particularly hippos, perish when the channel dried after many years of flowing.

After the channel completely dried, pumped waterholes were created by safari operators along the channel to help sustain the wildlife, like elephant and buffalo, which had become used to the Savute's water over many years. Then in 2008, water began to creep down the Savute Channel again, with water again filling the channel by 2010 after 30 years of being dry.

Underground movements that cause slight shifts in the ground around the Linyanti Swamp are now understood to be the cause of the changes in the flow of water into the Savute Channel.

Lions crossing the newly flooded Savute Channel in the Linyanti region of Botswana (Copyright © James Weis).

Wildlife in the Greater Linyanti

The Linyanti area, including the Kwando and Selinda, is a superb destination for wildlife and certainly in most ways equal to that of Moremi and the main Okavango region. Elephants are very common, and found here all year, as are impala, greater kudu, giraffe, warthog, and reedbuck.

Blue wildebeest and zebra are present all year, but their numbers increase significantly from May through October. When the rains begin in November, the majority of zebra and wildebeest move towards Chobe National Park and the Savute Marsh. Buffalo arrive near the end of the rains or just after (May-June) to enjoy the fresh grasses and then disperse like the zebra when the rains begin.

African wild dogs are particularly cautious about entering deep water, as they know the dangers that can lie below the surface (Copyright © James Weis).

Lion are common in the Linyanti region, as are leopard and spotted hyena. Cheetah are seen occasionally on the open plains, particularly on the grassy bed of the Savute Channel if it is not full of water. The region is one of the best areas in Botswana, and indeed all of Africa, to see and enjoying sightings of the endangered Africa wild dog. The area has an abundance of impala, which are the favorite prey of the dogs.

Both black-backed and side-striped jackal are found in the Linyanti, as are African wild cat, serval, caracal, bat-eared fox, aardwolf, and various species of mongoose.

Sable and roan antelope, which are uncommon throughout their limited ranges in Botswana, are both found in the Linyanti region. Red lechwe antelope, which are never found far from permanent water, live along the Linyanti River system and seen in good numbers along the floodplain and in the reed beds. Hippo are likewise found alongside the red lechwe. The shy and elusive sitatunga is also here, though difficult to see.

Red lechwe antelope are never found far from permanent and sufficiently deep water, which they run into to escape predation. The hind quarters of these animals have evolved to allow them to leap through deep water at high speed (Copyright © James Weis).

Birding in the Greater Linyanti

The diversity of habitats and the relative prevalence of year-round water makes this region a very good one for birds. The numbers and diversity of species jumps during the summer months, when huge numbers of Palearctic species arrive to breed beginning around September, before departing in late March/April.

Raptors and vultures are very common, as are a multitude of drylands species like starlings, barbets, coucals, cuckoos, bustards and so many more. Waterbirds and found in good numbers along the permanent waterways and throughout the region during the rainy summer season (December thru March).

Read full details on the Linyanti, Kwando, and Selinda and its safari camps and lodges here.

Birding in the Greater Linyanti is very good, especially during the spring and summer months (November thru March) when numerous migratory species arrive from the Palearctic region. Shown are a kori bustard with a Carmen bee-eater as passenger (Copyright © James Weis).

Chobe National Park

Botswana's first proclaimed national park, Chobe (pronounced "CHO-bee") is located to the northeast of the Okavango and borders the Chobe River in the far north of Botswana.

The best wildlife viewing in Chobe is along the Linyanti and Chobe Rivers on the park's northern boundary. This riverfront area is especially productive for wildlife during the latter part of the dry season, between July thru October. As the rains end around late March or into April, the natural waterholes start to dry up and the wildlife begins moving off to the Okavango Delta or north towards the permanent water of the rivers.

Elephants often swim in the Chobe River; here a herd emerges onto the Namibian banks after swimming across, while another large herd can be seen drinking on the distant Botswana bank (Copyright © James Weis).

Chobe is situated on Kalahari Desert sand, with vegetated sand ridges and areas of sand dunes. Chobe has a lot of clay pans that provide drinking water for the animals during the rainy season between December and March.

Large mammals in Chobe include elephant, Burchell's zebra, giraffe, impala, blue wildebeest, tsessebe, greater kudu, and warthog. Eland, roan, and sable antelope are also present in small numbers.

Lion and spotted hyena are the most common predators and both species are seen regularly. Other predators seen on occasion include African wild dog, cheetah, and leopard. Caracal, serval, black-backed jackal, and side-striped jackal are also found in Chobe.

Critically endangered African wild dogs are seen throughout Northern Botswana, including the occasional sighting in Chobe National Park (Copyright © James Weis).

Hippo and crocodile are found in huge numbers in the Chobe River. Rhinos once lived in Chobe, but have been locally extinct in the park since the 1990s. Note that the rhino reintroduction program initiated on Chief's Island in the Okavango Delta during the early 2000s resulted in a wide dispersal of some of the released animals, some moving as far as Nxai Pan, so it is possible that rhinos could one day be seen again in Chobe.

Birding in Chobe is very good, with a bird list of around 450 species. The Chobe River offers superb opportunities for up-close viewing of waterbirds, raptors, kingfishers, bee-eaters and many more. Inland from the river are a good variety of woodland and grassland species.

Chobe offers two prime wildlife areas within its boundaries: the Chobe Riverfront on its northern boundary and the Savute Marsh, which is located inland further south.

A hippo out for grazing along the Chobe River, as a cattle egret watches.

Chobe Riverfront

The Chobe Riverfront offers extremely good wildlife viewing between July and October, which is the middle to the end of northern Botswana's dry season. During these dry months, little to no rain falls and any rainwater and natural waterholes in the park have become mostly or completely dried up. For this reason, large numbers of elephant, buffalo, and other plains game are forced to stay close to the Chobe River to have access to drinking water.

Wildlife viewing along the Chobe River is mainly done from a boat, with twice daily excursions, but the roads within the park that run parallel to the river also offer excellent game viewing during this time.

The Chobe River is a great place to get up close views of elephants drinking along the banks and oftentimes they can be seen swimming or just frolicking in the river. The river is also full of crocodiles, including many that are huge, as well as an abundance of hippos. Photographic opportunities from the safari boats are superb.

The dry season, especially from late July to mid-October, is a spectacular time for boat-based safaris on the Chobe River. During this time, large numbers of elephant and other wildlife gather on the banks of the river to drink (Copyright © James Weis).

Besides elephant and buffalo, common animals along the Chobe river include red lechwe, waterbuck, greater kudu, impala, and many more species. Lion are seen often and African wild dogs are also possible. Leopard are seen from the boats on occasion but are more easily seen on a game drive from a vehicle. Baboon and vervet monkey are seen in the riparian trees along the river, but are also seen more easily from a game drive.

Raptors and water birds along the river are another feature of river-based safaris, with plenty of fish-eagles, tawny eagles, snake eagles, kites, and vultures. Other birds common along the river include African skimmers, which nest on the sand banks in some places, bee-eaters, kingfishers, herons, egrets, and a multitude of passerines.

During the rainy months, between mid-November and early May, the wildlife disperses inland, and the game viewing along the river is nowhere near as good.

There is a wide range of accommodation located along the Chobe Riverfront, as well as in the tourism-based small town of Kasane, and all offer game drives and boating safaris on the river.

Boating on the Chobe River provides excellent opportunities to see large mammals, reptiles, and birds. Here is a giant kingfisher eating a crab she has caught (Copyright © James Weis).

Savute Marsh

Most of Chobe National Park away from the far northern stretch along the Chobe River is a mix of sand, thick scrub, mixed woodland, and cathedral mopane-tree forest. Located in the southwest of Chobe National Park is a marshy area that is fed by seasonal rain and sometimes by the on again, off again water that flows in via the Savute Channel.

The Savute Channel empties out of the Zibadianja Lagoon at the southern tip of the Lintantyi Marsh, but only flows depending on tectonic shifts in the ground far below the sands around the marsh. The channel has undergone long periods of alternating flow and dryness lasting decades, changing it from an open grassland to a flowing river.

The area around the Savute Marsh is mostly thorn scrub, with Acacia, Terminalia, and mopane trees dominating the landscape. Other vegetation includes tracts of Combretum bushes and Kalahari apple-leaf shrub. Baobab trees are interspersed in the dry areas outside of the marsh.

The Savute Marsh area is well-known its lions. Here a pride drinks at a waterhole near the marsh.

The alluvial deposits brought in by the centuries of water flowing from the Savute Channel have resulted in rich grasslands in the channel and around the marsh itself. The 'skeletons' of long-dead camelthorn (Acacia erioloba), umbrella-thorn (Acacia tortilis), and leadwood (Combretum imberbe) trees still stand in the grasslands. These trees grew in the long dry period between 1885 and 1955, when the Savute Marsh was dry and subsequently perished when the marsh flooded again in the late 1950s.

To support wildlife in the area around the marsh, several permanent waterholes have been built with pumps to keep them filled. During the dry season these pumped waterholes sustain the region's animals.

Wildlife around the Savute Marsh is seasonally abundant, with large numbers of blue wildebeest and Burchell's zebra moving into the marsh at the end of the rainy season (April/May) to take advantage of the fresh grass. Herds of buffalo are also sometimes seen, especially if the Savute Channel has water.

Chobe National Park is well known for elephants, with many bulls that are resident in the park (Copyright © James Weis).

The marsh is well known for its elephants, with numerous old bulls that are residents of the area, as well as breeding herds that pass through on their way to the Okavango or north to the Chobe River.

Lion and spotted hyena are found around the marsh in good numbers and leopard also do well in Savute. On the southern side of the marsh, giraffe and oryx are sometimes seen. Other predators commonly seen include cheetah, African wild dog, and black-backed jackal.

Birding around the Savute Marsh is very good, with water birds in the marsh during the wet months (December thru March) and drylands species in the wooded areas throughout the year.

There are permanent safari lodges located near the pumped waterholes on the northern side of the marsh and several camping sites, which are used by overland safari operators.

Read full details on the Chobe National Park and its safari camps and lodges here.

Cheetah brothers in the Savute Marsh, Chobe National Park, Botswana.

Makgadikgadi

(including two national parks: Makgadikgadi Pans NP and Nxai Pan NP)

Makgadikgadi History

The Makgadikgadi region is dominated by a series of large salt pans, situated in dry northern Kalahari Desert in north-eastern Botswana. The pans are the remnants of a large paleo-lake that formed some 2 million years ago, fed by the Okavango, Chobe, and Upper Zambezi Rivers.

These rivers had previously flowed south through Botswana, all the way to the Limpopo (on the southern border of Botswana), which flows east to the Indian Ocean. Tectonic uplifting in central Botswana cut off the southward drainage of these rivers, diverting the flow and leading to the formation of Lake Makgadikgadi. Over millennia, the lake levels rose, eventually covering an area of 100 000 square miles (275 000 sq kms).

Kudiakam Pan in Nxai Pan National Park, with Baines' Baobabs in the foreground.

Some 20 000 years ago, the lake filled to capacity and began to overflow to the northeast as a river that eventually connected with the middle Zambezi River, which eventually led to the formation of a gorge and the Victoria Falls. As time passed, the levels in Lake Makgadikgadi decreased and a drier climactic period in the region ensued, increasing evaporation of the lake's water.

Around 10 000 years ago, further tectonic movements formed a basin to the northwest of Lake Makgadikgadi, leading to the formation of the Okavango Delta, which further decreased the inflow of water into Lake Makgadikgadi. As the lake levels shrank, smaller lakes formed with progressively smaller shorelines. Eventually, the continued evaporation of water in these lakes led to the complete drying of all permanent water, leaving behind a series of salty, clay pans.

Makgadikgadi's salty, clay-covered pans are the remnants of a vast paleo-lake that dried up around 10 000 years ago.

Makgadikgadi Geography

The Makgadikgadi is actually a series of pans, the largest of which are Ntwetwe Pan and Sua Pan. A large number of smaller pans are interspersed between and around the two large pans. The pans are covered in a whitish or gray, salty, clay crust, but in years of good rainfall, the pans may temporarily become filled with shallow water with fresh grass in the surrounding savanna.

Around the pans are grasslands, fossilized dunes, and acacia scrub. The are also some small, granite outcrops scattered across the region. There are long lines of fencing bordering the pans on the south, with large openings on the north and east, allowing wildlife to pass through the region.

The famous baobab tree known as Chapman's Baobab, which until 2016 stood just north of Ntwetwe Pan, was estimated to be around 1 500 years old and was famously used as an early 'postal drop off' by early European explorers passing thru the area. The tree unfortunately fell in January 2016. Another large and renowned baobab known as Green's Baobab still stands nearby.

The small granitic Kubu Island in Sua Pan.

Besides seasonal rains, which fall between December and March, the only significant source of water to the pans is the Nata River, which originates to the northeast in Zimbabwe (where it is called the Amanzanyama River). On the western side of the pans, the Boteti River, which drains from the southern Okavango Delta and only flows during years of large flooding, also supplies water to the area.

Two small granitic rock islands (Kokome Island and Kubu Island) are located in Sua Pan. Kubu Island is the site of archeological findings showing the existence of ancient humans living around Lake Makgadikgadi and is protected as a national monument. The island is also the site of a number of old baobab trees and is used as an overland camping site.

The small Nata Sanctuary, which was established to provide protected seasonal habitat for breeding waterbirds, is located at the northeast corner of Sua Pan, at the Nata River delta.

Read full details on the Makgadikgadi and its safari camps and lodges here.

During the summer rains (December through March), the pans in Makgadikgadi may fill with shallow water.

Makgadikgadi Pans National Park

A portion of the western side of Ntwetwe Pan, as well as a vast area of sandy savanna grassland and fossilized dunes is protected by the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park (MPNP). The park extends to the usually mostly-dry Boteti River.

Wildlife in MPNP is seasonally excellent, when large numbers of Burchell's zebra and blue wildebeest gather along the Boteti watercourse during the winter months between June and December. These grazers begin moving towards the Boteti at the end of the rainy season, usually around May, to take advantage of the fresh grasses along the western side of the park.

Zebras gathered at the Boteti River in Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, Botswana.

Besides the zebra and wildebeest, the Boteti attracts smaller numbers of elephant, greater kudu, waterbuck, eland, oryx, red hartebeest, and bushbuck. The occasional white rhino has been spotted in the park.

When the rains begin to fall in summer, usually by mid-December, much of the wildlife around the Boteti River disperses to take advantage of the grazing that becomes available in the interior of the park, as well as further north outside of the park around Nxai Pan and beyond.

Predators found in MPNP include lion, which due to the low densities of their prey, are typically found in small groups, as well as cheetah, leopard, brown hyena, black-backed jackal, and spotted hyena.

Elephants at the Boteti River, Makgadikgadi Pans National Park.

Birding in MPNP is good, with several distinct habitats adding to the diversity of the species. Ostrich and kori bustard are the largest and most obvious species. The vast grasslands covering the majority of the park are home to a variety of bustards, pipits, larks, and sandgrouses. Other common grassland birds include the secretarybird, greater kestrel, marsh owl, and pale-chanting goshawk. Eagles, vultures, goshawks and falcons are also seen regularly.

All of the permanent safari camps are located outside of the park, with those on the eastern side situated near the northern edge of Ntwetwe Pan and those in the west along the Boteti River.

Read full details on the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park and its safari camps and lodges here.

Greater flamingos arrive to feed on algae in the Makgadikgadi Pans.

Nxai Pan National Park

Adjoining the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park to the north (with the Maun-Nata Road as the separating boundary), is Nxai Pan National Park (NPNP). This northern section of the remnants of Lake Makgadikgadi, a huge paleo-lake that dried up around 10 000 years ago, sits at a slightly higher elevation than the southern pans, so it has less leached salts and supports more vegetation.

The Nxai Pan area is characterized by grassy savanna with Acacia tortilis scrub and it has a similar look to the Serengeti and Masai Mara grasslands of East Africa (but without all the tourist vehicles). Within the grasslands are several small pans left over from Lake Makgadikgadi. Today, these small pans are mostly covered in grass, but there are small pans that fill with water during the rains. Surrounding the pans are fossilized dunes of Kalahari sand.

The cluster of baobab trees known as Baines' Baobabs situated on the edge of Kudiakam Pan, were famously immortalized by artist and adventurer Thomas Baines in 1862. Baines accompanied the famous explorer David Livingstone on his Zambezi expedition and painted the trees when the group visited the region. The trees have changed little since that time.

Zebras grazing on the rich grass in Nxai Pan National Park.

The major rivers that once fed Lake Makgadikgadi have diverted their courses to the Okavango and Zambezi, so there are two pumped pans that support the area's wildlife during the long dry season between June and October.

During the rainy season (December thru April), Nxai Pan National Park becomes a lush, green grassland that attracts large herds of blue wildebeest and Burchell's zebra, many of which arrive from the Boteti River area in Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, while others arrive from the north (Chobe and Okavango Delta). Large numbers of springbok are found in the Nxai Pan area, as well as good numbers of oryx, eland, and red hartebeest.

Greater kudu and impala arrive to browse and graze around the mopane-tree woodland and herds of giraffe come to feed on the Acacia trees north of the pans. The Nxai Pan area is one of the few places where impala and springbok are commonly seen together. Tsessebe are found in small numbers, this being the southern extent of their range. Breeding herds of elephant arrive as well, feeding on the new grasses, Acacia trees, and mopane trees.

A lion scans a waterhole in Nxai Pan National Park, with zebras and springboks.

Of course, the big herds attract predators, including lion, cheetah, African wild dog, and spotted hyena. Bat-eared fox are abundant, as are black-backed jackal. Meerkats are always fun to watch and there is a habituated group that can be visited from Jack's Camp or San Camp.

With all of this wildlife and the spectacular setting, game viewing in Nxai Pan during the green season (December-April), especially during the onset of this period, can be nothing short of superb. Many of the herbivores give birth at this time as well, adding to the overall drama and making for interesting wildlife interactions.

Birding in Nxai Pan is very good, with over 200 species possible, consisting of a mix of grassland and woodland species.

There is one permanent safari camp in NPNP, as well as several camping sites, which are used by self-campers and organized overland group safaris.

Read full details on the Nxai Pan National Park and its safari camps and lodges here.

Meerkats (or suricates) are a special treat to see in the Makgadikgadi (Copyright © James Weis).

Central Kalahari Game Reserve

Named for the Kalahari Desert, within which it is located, the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) covers a massive area situated roughly in the center of Botswana. The CKGR is one of the world's largest reserves, covering some 20 400 square miles (52 800 sq kms).