Kenya

Region Links: Amboseli & Chyulu Hills, East Coast Kenya, Great Migration, Laikipia, Masai Mara, Nairobi, Rift Valley & Central Highlands, Samburu, Tsavo

Highlights

- One of Africa's top safari destinations.

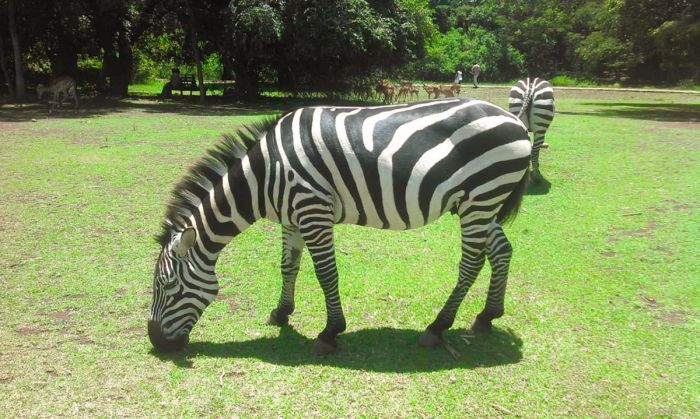

- Masai Mara's wildebeest and zebra migration (August-October) and big cats year-round.

- Amboseli's elephants with stunning views of Mount Kilimanjaro, a photographer's paradise.

- Lewa and Ol Pejeta Conservancies for great rhinos and other wildlife.

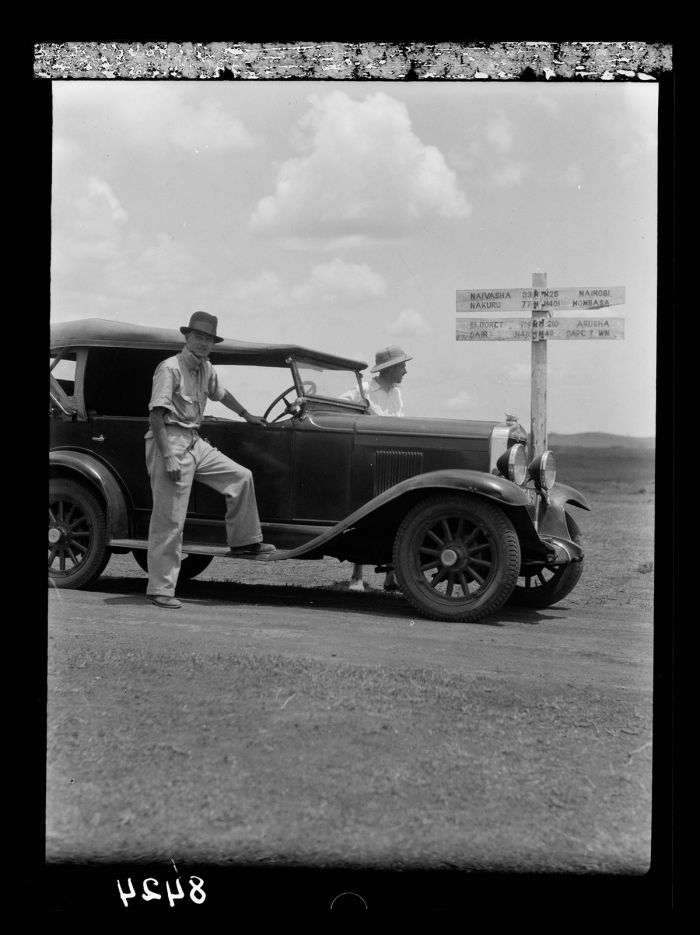

- Lakes Nakuru and Naivasha in the Great Rift Valley.

- Mount Kenya, Africa's second-highest peak.

- Indian Ocean coastal resorts for beautiful beaches and history/culture.

Kenya is one of Africa's prime safari destinations and home to the Masai Mara and the Great Migration. Amboseli offers wildlife with Mount Kilimanjaro as a backdrop and the East Coast boasts pristine Indian Ocean beaches and resorts.

The Great Migration of wildebeests and zebras in the Masai Mara.

The Masai Mara National Reserve and the surrounding private conservancies are certainly Kenya's top wildlife destination. The 'Mara' adjoins Tanzania's Serengeti across the border and together, they host the largest mammal migration on Earth. A safari to the Masai Mara is included on most Kenya itineraries.

Cheetah and small cubs in the Masai Mara.

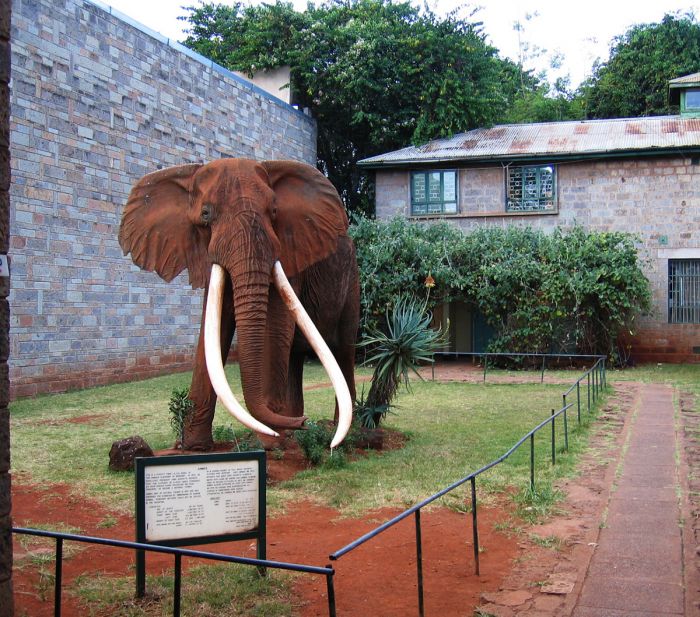

Amboseli National Park lies on Kenya's border with Tanzania and is famous for its abundant herds of relaxed elephants and its setting beneath Africa's highest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro. Some of Africa's last "big tusker" elephants are known from the region.

An elephant in Amboseli and Mount Kilimanjaro (Copyright © James Weis).

The Tsavo region encompasses two massive national parks, Tsavo East and Tsavo West, which combined make up one of the world's largest protected wildlife reserves. Tsavo is mostly wild and undeveloped, giving it a feeling of true wilderness, yet still offering very good safaris, especially along the perennial rivers.

A male lion in Tsavo with its distinctive red sand.

Africa's Great Rift Valley cuts through Kenya and along its edges are the Central Highlands, which includes Mount Kenya and the Aberdare Mountains. Several Rift Valley lakes, including Naivasha and Nakuru offer wildlife reserves and adventure.

Lesser flamingos at Lake Nakuru in Kenya's Rift Valley.

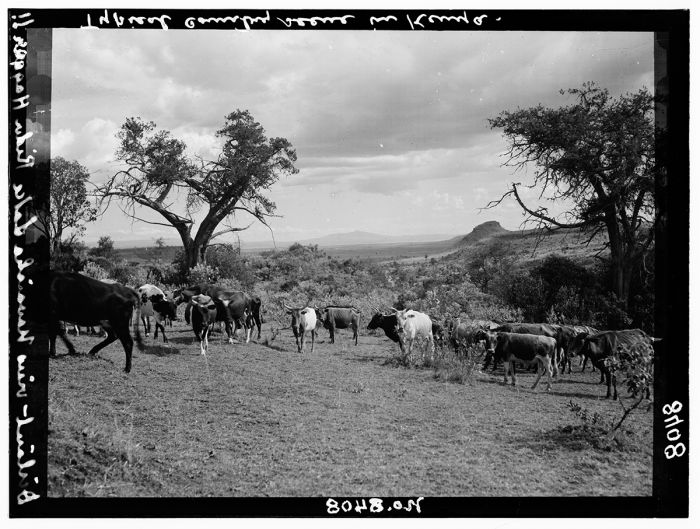

The Laikipia region is known for its patchwork of conservancies and working cattle ranches that coexist with the abundant local wildlife. It is considered Kenya's greatest conservation success region, with no national parks, but numerous community-run ranches that offer safaris and accommodations. It is a unique and rewarding destination to visit.

Grevy's zebras in Kenya's Laikipia region.

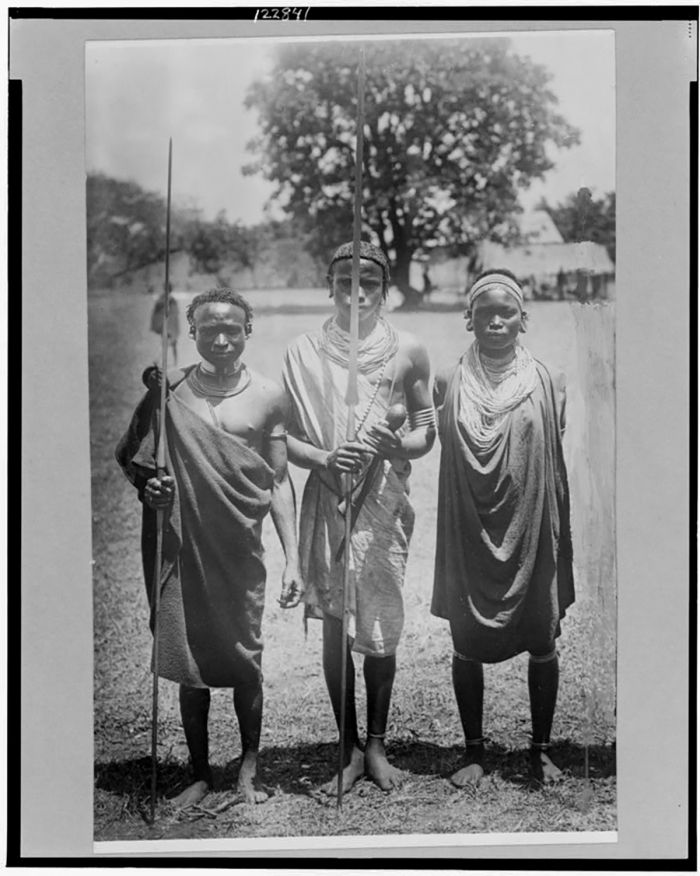

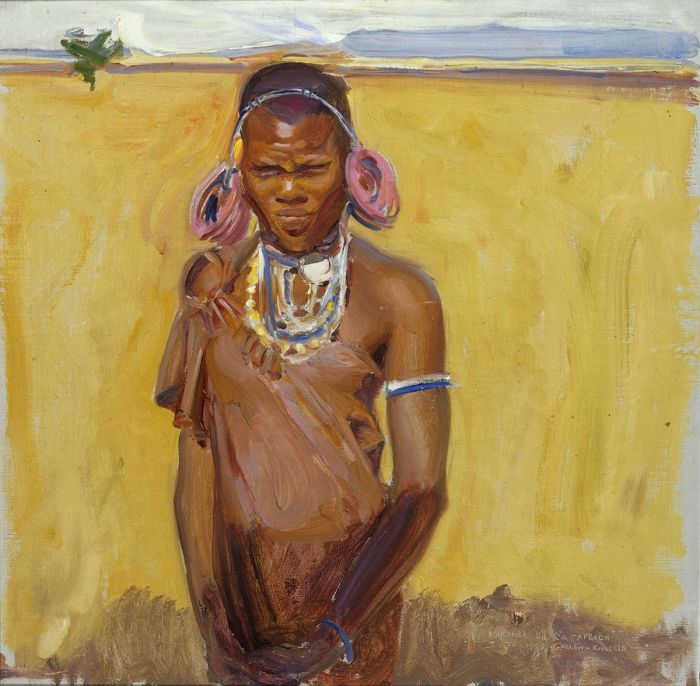

The Samburu region is Kenya's northernmost safari destination and is so named for the colorful Samburu people who inhabit this dry low-lying region. Samburu is rich in cultural experiences and offers year-round viewing of dry-land wildlife. The life-giving Ewaso Ng'iro River flows through the reserves of Samburu, Buffalo Springs, and Shaba.

An beisa oryx in Kenya's Samburu National Reserve.

Kenya's East Coast offers miles of Indian Ocean shoreline, with rich history, some good wildlife reserves, and uncrowded beaches. The historic town of Lamu in the far north is remote and full of culture while the south coast at Diani Beach offers superb resort getaways. Mombasa, Kenya's second-largest city is the major port on the coast.

Indian Ocean beach at Diani Beach, Kenya.

Nairobi is the main gateway for most international travelers and is normally a stopover rather than a destination. Surprisingly, Nairobi National Park offers good wildlife viewing in the shadows of the city and is worth a visit on a spare morning or afternoon.

A safari in Kenya holds the promise of once-in-a-lifetime sights and special memories!

Black rhino female and her calf in the Masai Mara National Reserve.

kenya regions

Masai Mara (incl. surrounding conservancies)

Visit Kenya's premier wildlife destination for an incredible wildlife experience. Watch the annual great migration of wildebeests and zebras as they follow an ancient cycle in search of grazing. All the big cats and iconic wildlife here year-round. More

Amboseli (incl. Chyulu Hills)

Discover this wildlife haven with its herds of elephants marching in the dust with Mount Kilimanjaro in the background. A photographer's paradise! More

Laikipia Plains (incl. Lewa, Borana & Ol Pejeta)

The Laikipia region is one of Kenya's great success stories. Ranchland merged with indigenous tribes and superb wildlife make it more than worth adding to an itinerary. The Lewa and Ol Pejeta Conservancies protect rhinos and other species and offer numerous lodges and excellent game viewing. More

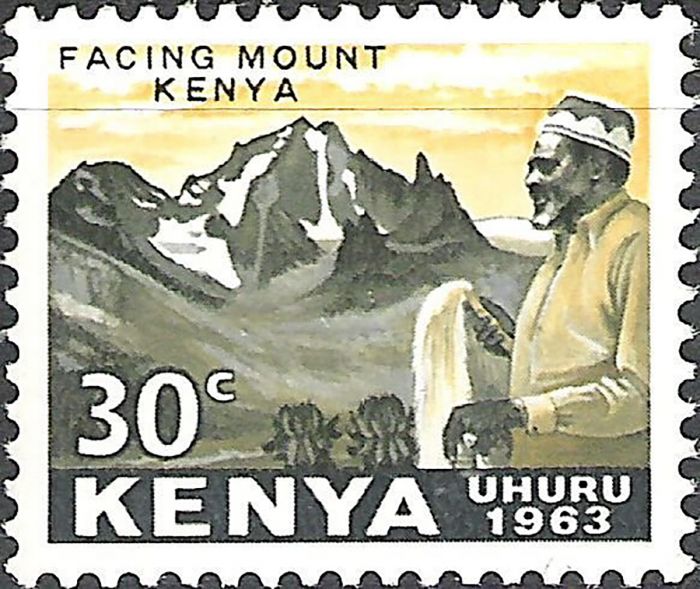

Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya, a 3.5-million-year-old extinct volcano, is Africa's second-highest peak. The National Park of the same name, encompasses all parts of the mountain above 3 200 meters. Climb on any of its routes to the top or explore the slopes by staying in one of its lodges. More

Rift Valley & Highlands (incl. Aberdare, Lake Nakuru, Lake Naivasha)

The Rift Valley region includes Lakes Nakuru and Naivasha, both offering relaxing safaris on and around the water. Hell's Gate National Park offers wildlife and walking safaris in the gorge. The Aberdares offer lovely, high moorland exploration and is famous for its elephants. More

Samburu (incl. Buffalo Springs, Shaba)

Home to the semi-nomadic Samburu people on the frontier of Kenya's arid north. The reserves here offer a wide variety of wildlife and drylands birds. The beautiful, palm-lined Ewaso Ng'iro river flows through the region. Elephants, baboons and hippo are here in large numbers. More

Tsavo (incl. Tsavo East, Tsavo West)

The adjacent national parks of Tsavo East and West combine to form Africa's largest wildlife reserve. Dry bush lands offer wild and untamed habitat with plenty of animals. Mzima Springs is a lush oasis with underwater viewing of hippos and crocs! More

Indian Ocean Coast (incl. Diani Beach, Lamu, Malindi, Watamu, Mombasa)

Kenya's Indian Ocean coast offers a multitude of resorts and several marine national parks. South of Mombasa lies Diani Beach, with an assortment of oceanfront accommodation. Lamu in the far north is a World Heritage Site offering a lazy and relaxed atmosphere and perhaps Kenya's best-kept secret. More

Nairobi (incl. Nairobi National Park)

Kenya's capital city is most likely on everyone's Kenya itinerary at some point. The city is bustling place with a population of over 6 million in the metropolitan area. A visit to the David Sheldrick Elephant Orphanage is a must! More

Read More...

Main: Flora, Geography, Important Areas, National Parks, Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, UNESCO Sites, Urban Areas, Wildlife

Detail: Aberdare, Amboseli, Central Highlands, Chyulu Hills, Diani Beach, Great Migration, Laikipia, Lake Naivasha, Lake Nakuru, Lake Turkana, Lake Victoria, Lamu, Lewa, Mara Conservancies, Masai Mara, Mombasa, Mount Kenya, Nairobi, Ol Pejeta, Rift Valley, Samburu, Tsavo, Watamu

Admin: Travel Tips, Entry Requirements/Visas

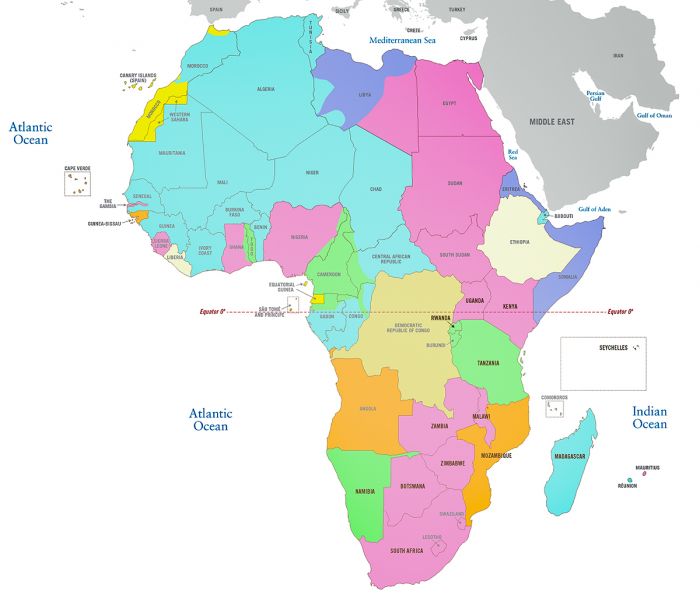

GEOGRAPHY

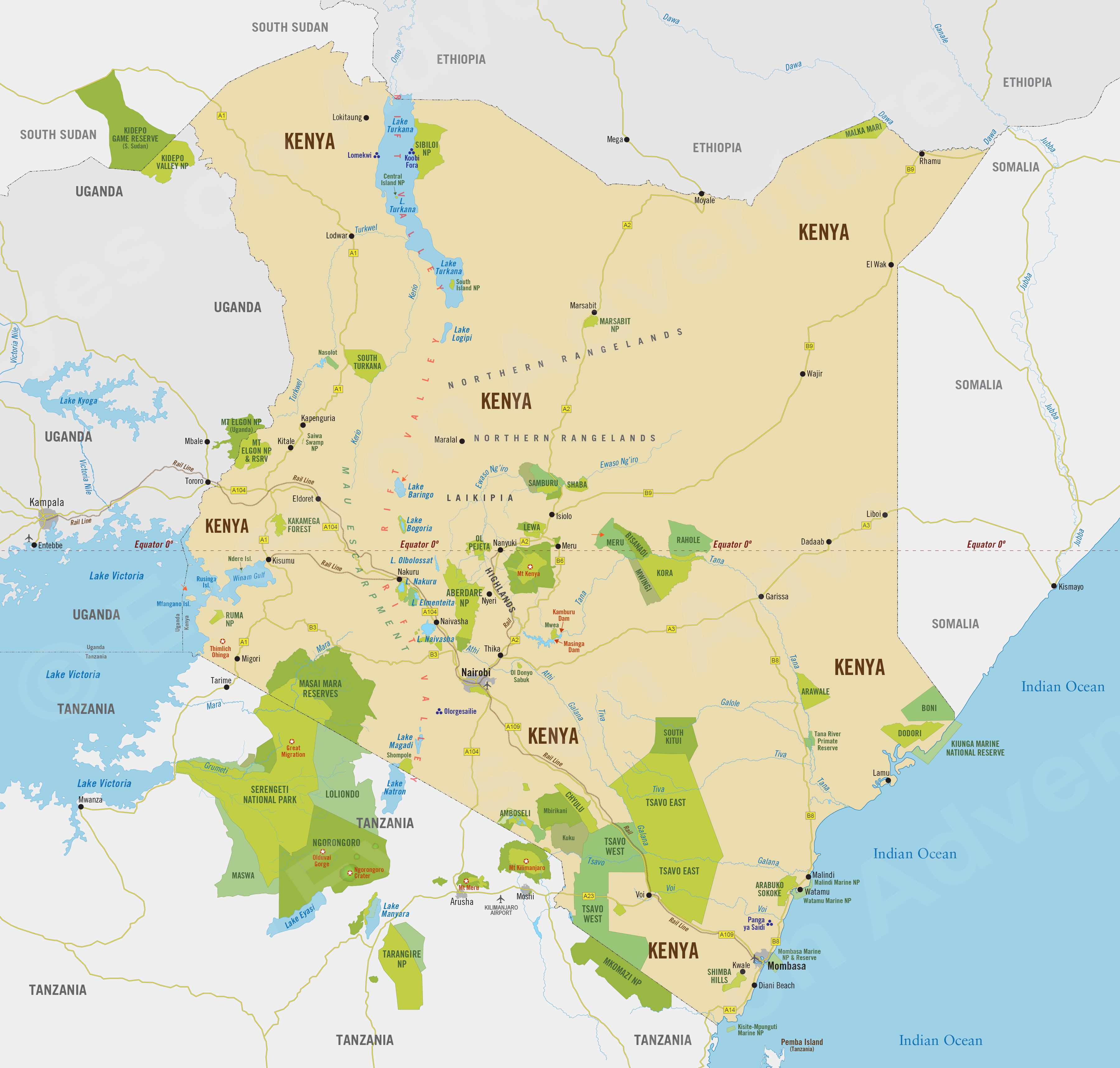

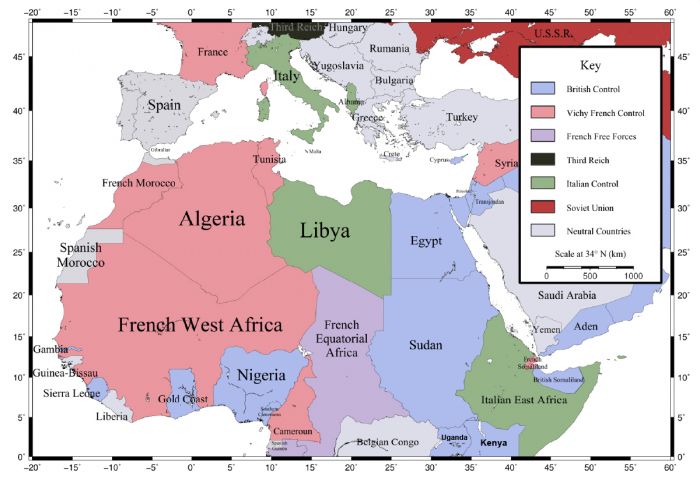

Kenya is located in the greater region known as East Africa. It shares border with Tanzania, Uganda, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Kenya's east coast is formed by 333 miles (536 kms) of Indian Ocean shoreline. The equator passes through the middle of the country.

A cheetah in the Masai Mara (Copyright © James Weis).

Kenya's topography is varied, with mountain ranges formed by the East African Rift, lakes, a few significant rivers, grasslands, forests, and a long Indian Ocean coastline. Mount Kenya is the highest peak in the country and Africa's second-highest at 17 057 feet (5 199m).

Kenya can be generally described in the following geographic regions: the semi-arid and arid regions in the north, the Rift Valley and its associated Central Highlands, the eastern plateau and ocean coast, the Lake Victoria basin, and the southern grasslands.

The Gregory Rift, which forms part of the East Africa Rift, cuts through Kenya north-to-south on a vector just west of Nairobi. In the valley of this rift are numerous notable lakes, including Turkana, Baringo, Bogoria, Nakuru, Elmenteita, Naivasha and Magadi. This rifting has also been responsible for the formation of Kenya's Central Highlands, which include Mount Kenya and the Aberdare Mountains.

West of Kenya's Rift is the westward-sloping Mau Escarpment, which gradually descends to its lowest point at Lake Victoria on Kenya's western border with Uganda.

Elephants in Amboseli National Park and Mount Kilimanjaro in the distance.

Kenya's notable rivers are the the Tana and Galana, which rise in the eastern highlands and flow southeast to the Indian Ocean, and the Ewaso Ng'iro, which rises on the slopes of Mount Kenya and flows north and then northeast into Somalia. The Mara River originates in the Napuiyapi swamp in the Mau Forest and flows south through the Masai Mara Reserve, into the Serengeti of Tanzania, and then west into Lake Victoria.

Kenya's protected areas are categorized as national parks (managed by the Kenya Wildlife Service-KWS), national reserves (managed by county governments and/or KWS), and conservancies (privately managed, often in joint ventures with local communities). The country's national parks and reserves cover about 8% of the total land area, with conservancies protecting an additional 11% of land. Tourism accounts for roughly 10% of Kenya's GDP.

Maasai men in the Masai Mara Game Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Flora

Kenya's position atop the equator, as well as the wide range of elevations created by the Great Rift Valley that runs through the western side of the country, give it a huge diversity of habitats and flora. High mountains, deep valleys with lakes, Indian Ocean coastline, and arid semi-desert are some of the biomes that can be found in Kenya, each with its own distinctive vegetation.

Generally speaking, the northern half of Kenya is quite dry, covered by sparse vegetation, while areas to the south receive more rain. The volcanic Central Highlands, including Mount Kenya and the Aberdare Mountains, provide water for the country's major rivers, most of which flow eastward towards the Indian Ocean.

High elevation vegetation near the summit on Mount Kenya.

Forests

Kenya's most diverse floral regions are along the volcanic highlands associated with the Rift Valley. Mount Kenya, the Aberdare Mountains, Mount Marsabit, Mount Elgon, and the Mau Escarpment are rich in floral diversity, with montane forests that are mostly protected in national parks. Vegetation zones change as the elevation increases, with bamboo forest on the lower slopes, alpine forest further up, and moorlands at the higher elevations. Mount Kenya's highest elevations are deprived of most vegetation and often still covered in snow.

Another of the country's diverse floral areas is the relatively small and isolated Kakamega Forest in Western Kenya, just north of the equator. Kakamega is all that remains of the easternmost portion of the ancient Guineo-Congolian rainforest that once spanned most of the continent.

Kakamega is a floral island in the middle of a highly populated rural part of the country, but still survives under various forms of local protection. Kakamega contains around 400 species of plants, including 170 flowering species, 150 different trees, and 60 species of orchid, of which nine are endemic to the forest. More species are still being discovered here.

A waterfall in lush forest, Aberdare Mountains, Kenya.

Most of Kenya's low-elevation forests have disappeared outside of the protected parks and reserves, having been cleared long ago by humans for agriculture. What still remains is mostly restricted to small bands and pockets of forest along the Indian Ocean coastal strip and some riparian forest along the lower Tana River in southeast Kenya.

The coastal forests that remain in Kenya are small remnants of a once vast band of coastal forest that stretched from present-day Somalia in the north, all the way to Mozambique south of Tanzania. The largest and best preserved of Kenya's coastal forest is the Arabuko Sokoke Forest, located just inland from Malindi town. The forest contains zones of mixed lowland rainforest, Brachystegia woodland, and Cynometra forest, all of which are rich in both flora and bird life, with over 500 species of plants recorded.

Walking trail thru Kakamega Forest, Kenya.

Grasslands

Open savanna covered in grass and interspersed with Acacia trees is the iconic ecosystem of the Masai Mara and Serengeti. The Mara-Serengeti plains are home to East Africa's greatest concentration of wildlife, with millions of herbivores feeding on the rich grasses that cover this region.

The richness of these grasses is due to the fertile volcanic soils that cover the area, combined with good rains that come twice a year and last for several months. These tropical grasslands are considered part of the 'Southern Acacia–Commiphora bushlands and thickets' ecoregion or biome.

Beyond the Masai Mara, much of the country, including most of southeast, central and northwest Kenya is part of the 'Northern Acacia–Commiphora bushlands and thickets' biome. Similar to the Masai Mara grasslands, but typically more arid, these grasslands, scrublands, and savannas stretch from the Kenya-Tanzania border east of the humid coastal belt and include Tsavo, Meru, Nairobi, Samburu, South Turkana, Marsabit, and northwest into parts of Uganda and South Sudan.

Zebras and topi on the short grass plains of the Masai Mara (Copyright © James Weis).

Wetlands

Kenya's wetlands are limited to its lakes and rivers, as well as some estuaries and wetlands along its eastern coastline. The Rift Valley cuts through western Kenya in a roughly north-south direction, and the valley contains lakes, most of which are endorheic (no outlet) and thus quite high in salts and minerals. Kenya's major Rift Valley lakes include (from north to south) Turkana, Logipi, Baringo, Bogoria, Nakuru, Elmenteita, Naivasha, and Magadi.

The highlands to the east of the Rift Valley, including the Aberdare Mountains and Mount Kenya, are the only major watersheds in Kenya, and the precipitation on these high slopes creates Kenya's only major rivers, including the Tana, Ewaso Ng'iro, and Athi-Galana.

Amboseli National Park has a series of small swamps that are fed from underground water flowing from Mount Kilimanjaro, located to the south in Tanzania. Lake Amboseli fills seasonally to a shallow depth depending on local rains.

Mangrove wetlands are found in the Lamu Archipelago on Kenya's northernmost coastline. In the southwest, the small portion of Lake Victoria that falls in Kenya contains papyrus swamps and marshlands along the shores.

Mangrove wetland at Mida Creek near Watamu, Kenya.

Wildlife

Masai Mara Wildlife

Kenya is one of Africa's top destinations for wildlife safaris and the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem is arguably Africa's premiere wildlife viewing venue. This ecosystem spans the border of Kenya and Tanzania, with the Masai Mara and its surrounding private conservancies forming the Kenyan portion of the land, while the Serengeti lies south of the border in Tanzania.

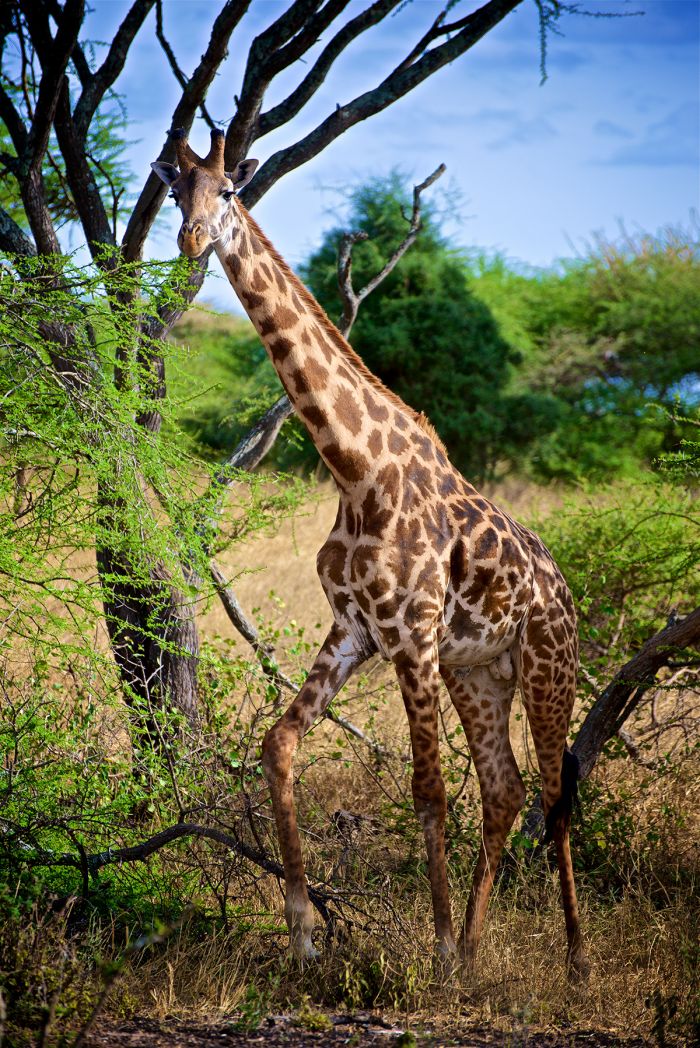

Africa's Great Migration, which sees roughly two million blue wildebeest and zebra on a continuous, clockwise trek across the Mara and Serengeti, attracts wildlife enthusiasts from around the world. The Masai Mara is known for this spectacle, as well as all its other resident wildlife, including lion, cheetah, leopard, elephant, giraffe, buffalo, spotted hyena, gazelles, antelopes, and many more iconic species.

The Great Migration arriving at the Sand River in the Masai Mara (Copyright © James Weis).

Beyond the borders of the Masai Mara National Reserve (MMNR) are multiple conservancies that are managed by various Maasai communities. Many of these conservancies (some are called Group Ranches), particularly those that directly border the MMNR, offer wildlife safaris that are as good or arguably superior to those inside the national reserve, as the safari camps and tourist numbers are far fewer than in the national reserve.

Big cats are a major draw in the Masai Mara, and it is surely one of Africa's best places to see them, especially cheetah, which do well in the Mara's wide-open grasslands, where they chase down Thomson's gazelle and other antelopes. Lions are also present in the Mara, often forming large prides and they sometimes compete with sizable 'clans' of spotted hyena for food, which can be an interesting interaction to see.

A pride of lions in the Masai Mara National Reserve (Copyright © James Weis).

Amboseli & Tsavo Wildlife

East of the Masai Mara along Kenya's southern border with Tanzania are Amboseli and Chyulu Hills, two national parks which lie in the shadows of Mount Kilimanjaro (which is located just across the border in Tanzania) and offer more wildlife safaris.

Amboseli is known for having some of Africa's last remaining "big tusker" elephants, owing to their decades-long protection from hunting and poaching here. The Chyulu Hills, lies east of Amboseli and offer a spectacularly scenic destination, with lower wildlife densities, but very few tourists.

Further to the east is the well-known Tsavo region, with two enormous national parks, Tsavo East and Tsavo West. Together these two parks make up the largest protected area in Kenya and one of the largest in the world. Tsavo is far less visited than Kenya's more popular reserves and it retains a wilderness feel. Tsavo West is the more visited of the two parks, but both offer good wildlife safaris, although the game viewing is a bit more challenging here than in the parks further west like the Masai Mara and Amboseli.

Elephants in Amboseli National Park, with Mount Kilimanjaro in the background.

Tsavo's landscape is one of red sand and wide-open spaces, with small regions of riverine forest and volcanic ridges. Tsavo's wildlife is abundant but often spread out in the large expanse of the parks. Species include elephant, lion, cheetah, giraffe, zebra, buffalo, various antelopes, and more.

Elephant and buffalo are a sure thing in Tsavo and they sometimes appear reddish, due to the color of the volcanic soil here. All of Africa's Big Five can be seen in Tsavo, including rhino, though they are only found in a protected sanctuary in Tsavo West. One of Africa's most unique animals, the gerenuk antelope, which is often seen standing on its hind legs to browse, can be seen in Tsavo.

Elephants in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya.

Nairobi Wildlife

Central Kenya is home to Nairobi, the country's capital and largest city, as well as the East Africa's main gateway for international travelers. Most visitors do not linger long in the city and head to other destinations the same day or spend a night before continuing on with their itinerary.

Nairobi National Park, which borders the city, offers surprisingly good wildlife viewing for those with an extra day to spend. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, which rehabilitates orphaned baby elephants, is located within Nairobi National Park and is highly recommended.

Lions in Nairobi National Park, Kenya.

Rift Valley & Central Highlands Wildlife

Africa's Great Rift Valley, which begins at the top of Africa in the Red Sea and cuts through Kenya, create habitats that are home to diverse wildlife. In the valley are Kenya's major lakes, which are bordered by grasslands and woodland and are home to good numbers of grazers and predators.

Along the eastern ridge of the rift are Kenya's Central Highlands, including Mount Kenya, Africa's second-highest peak, and the Aberdare Mountains, both of which also support iconic species, including elephant, buffalo, and leopard.

Flamingos on Lake Nakuru, one of Kenya's Central Rift Valley lakes.

Laikipia Wildlife

Located north of Kenya's Central Highlands and east of the Rift Valley is the wildlife-rich and diverse Laikipia Plateau. This region has no national parks, but instead has numerous privately run and community-based wildlife conservancies, some of which double as working cattle ranches.

Laikipia is considered a model of conservation success, where local people, ranching, diverse wildlife, and ecotourism coexist together. The major conservancies include Lewa, Ol Pejeta, Borana, Sosian, and Mugie. The Laikipia conservancies are one of the last places where wild rhinos can be seen reliably.

Masai giraffes in Hell's Gate National Park, Kenya.

Samburu Wildlife

Directly east of Laikipia is the Samburu Region, with three notable reserves: Samburu, Buffalo Springs, and Shaba. The Ewaso Ng'iro River, which rises from the western slopes of Mount Kenya and flows all the way to Somalia, provides the only year-long source of water to this otherwise arid region.

Samburu is home to diverse wildlife, including many regional dry-land species such as Grevy's zebra, beisa oryx, lesser kudu, Guenther's dik-dik, and gerenuk, The region also offers rewarding cultural experiences with the local Samburu people.

A leopard in Samburu National Park, Kenya.

East Coast Wildlife

Kenya's East Coast runs for 882 miles (1 420 kms) miles along the warm, turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean. There are white-sand beaches, historic towns like Lamu in the far north, Malindi and Watamu further south, and the major port of Mombasa. The south shores boast the popular Diani Beach, with resorts and private villas. Several wildlife reserves are situated just inland from the coast and there are numerous marine reserves protecting the fragile reefs offshore.

Kenya has set aside 26 national parks and another 19 as national reserves. There are also numerous privately managed wildlife conservancies that offer good wildlife viewing. Read more about each below.

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) in the Watamu Marine National Park, Kenya.

Protected Areas

Kenya has protected numerous national parks, reserves, and wildlife management areas (called group ranches or conservancies). Read about the details of each immediately below.

A bull elephant in Chyulu Hills National Park, Kenya (Copyright © James Weis).

National Parks

Following are Kenya's 26 national parks. The majority of the parks are situated in the central and southern portions of the country, with just a handful located in the remote and seldom visited northern portion. Additional information on each is included further below this list:

- Aberdare National Park - Protects the middle and upper elevations of the Aberdare Mountains. Beautiful and pristine habitat and plentiful wildlife. Completely fenced to minimize human-wildlife conflict. 'Tree' lodge accommodations.

- Amboseli National Park - Famous wildlife destination near the Kenya-Tanzania border. Plentiful wildlife, especially elephants, with Mount Kilimanjaro as a postcard-like backdrop. Protects several seasonal swamps and Lake Amboseli.

- Central Island National Park - One of two small island national parks in Lake Turkana in remote northern Kenya. Part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Chyulu Hills National Park - Protects a highland lava ridge east of Amboseli, with bordering 'group ranch' conservation areas in between the two parks. Seldom visited and spectacular scenery. Excellent wildlife safaris with very few tourists.

- Hell's Gate National Park - Small park on the southern side of Lake Naivasha protecting a deep gorge and plentiful seasonal plains game. Walking in the gorge (while sometimes viewing wildlife) is a highlight.

- Kisite-Mpunguti Marine National Park - Protects offshore Indian Ocean waters and Wasini Island near the southern border Kenya. Excellent snorkeling.

- Kora National Park - Part of a contiguous protected area that includes Meru NP, and several reserves (Bisanadi, Mwingi, Rahole) with semi-desert scrub habitat. Home of the late wildlife conservationist George Adamson. Seldom visited, but decent though sparse wildlife.

- Lake Nakuru National Park - Very popular destination in Kenya's Central Rift Valley, with diverse and abundant wildlife, including rhino, buffalo, giraffe, lion, leopard and many other species. Large numbers of flamingos gather seasonally on the lake. Self-drive or stay at one of the fully inclusive lodges.

- Malindi Marine National Park - Protects Indian Ocean water and marine life offshore from the town of Malindi. Good diving and snorkeling. Adjoins the Watamu Marine National Reserve.

- Malka Mari National Park - Located along the remote northeast border with Ethiopia. Protects semi-arid scrub and home to a variety of wildlife. Due to its location, very seldom gets visitors.

- Marsabit National Park - Located in seldom visited northern Kenya; protects land around Mount Marsabit, a massive, dormant shield volcano. The park has a variety of wildlife, notably elephants and offers very good birding.

- Meru National Park - Made famous by George and Joy Adamson, who lived and worked with lions here. Seldom visited, but offers good wildlife, lovely and unspoiled scenery, and a noticeable absence of tourists.

- Mombasa Marine National Park and Reserve - Protects waters offshore from Mombasa. Part national park, but the majority is a national reserve. Very good snorkeling and diving, with some very nice coral reefs.

- Mount Elgon National Park - Protects a small portion of Mount Elgon, an extinct volcano which straddles the western border with Uganda. Excellent hiking and rock climbing and some wildlife, but mainly a scenic park visited for the caves, forest, moorland, and trekking.

- Mount Kenya National Park - Protects the mid- and upper-elevations of Mount Kenya, Africa's second-tallest peak. Excellent hiking in the lower elevations and treks to the peak for the more intrepid. Forest lodges outside the park in the lower-elevation buffer zone.

- Mount Longonot National Park - Small park just south of Lake Naivasha protecting the stratovolcano of the same name (last eruption in 1860s). Hiking to the rim of the caldera is the main attraction; circumnavigating the rim takes 2-3 hours.

- Nairobi National Park - On the southern boundary with Kenya's capital city, the park offers surprisingly good game viewing and is unfenced on its southern border. Four of the Big Five animals are here (elephants missing), plus abundant plains game and very good birding. Worth a visit for those with a spare day or two in the city.

- Ndere Island National Park - Small uninhabited island just offshore in Lake Victoria. Protects hippos, crocodiles, various antelopes, and abundant bird life.

- Ol Donyo Sabuk National Park - Protects the mountain of the same name located just northeast of Nairobi. Offers good hiking and views of both Kilimnajaro and Mount Kenya. Wildlife still live on the slopes and is a popular day trip for locals living in Nairobi.

- Ruma National Park - Located in southwest Kenya, very close to Lake Victoria, the small park was created to protect Kenya's only population of roan antelope. Other species include Jackson's hartebeest, oribi, and Rothschild's giraffe. Leopard present but seldom seen. Visitors may have the park to themselves.

- Saiwa Swamp National Park - Tiny national park, created specifically to protect habitat and population of the semi-aquatic sitatunga antelope. Walking only on trails around the jungle and swamp. Various monkeys and birds.

- Sibiloi National Park - Remote park consisting of rocky, arid desert in far northern Kenya on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana. Created to protect numerous prehistoric hominid fossil sites. Part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- South Island National Park - One of two small island national parks in Lake Turkana in remote northern Kenya. Part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Tsavo East National Park - Largest national park in Kenya protects grassland and semi-arid Acacia scrubland. Much less visited than its sister park (Tsavo West), the park feels wild and remote. Wildlife viewing can be excellent and all the Big Five are present.

- Tsavo West National Park - Adjoins Tsavo East and has more varied terrain than its sister park. Game viewing is good, but the thick Acacia scrub can make finding animals difficult. All of Africa's Big Five are here. Mzima Springs' underwater observation hide is a top attraction.

- Watamu Marine National Park and Reserve - Protects Indian Ocean, tidal habitats (including Mida Creek) and marine life offshore from the town of Malindi. Good diving, snorkeling, and other water sports. Adjoins Malindi Marine National Park.

A buffalo relaxes on the shore of Lake Nakuru while flamingos take flight. The national park protects the lake and its wildlife.

Important Areas

Other important areas of note in Kenya include national reserves, national forests, group ranches, conservancies, general regions, and other attractions that are worth consideration when planning your trip.

- Arabuko Sokoke National Forest - Protects East Africa's last remaining tract of coastal forest. Superb for birding and also supports some primates and a small population of elephant.

- Arawale National Reserve - Borders the eastern side of the Tana River in northeast Kenya. Protects the only in-situ site of the critically endangered hirola antelope.

- Bisanadi National Reserve - One of three reserves contiguous with Meru and Kora National Parks. Semi-desert scrub habitat, except along the Tana River, where there is riparian forest. Good, though sparse wildlife and excellent birding. Few to no tourists.

- Boni National Reserve - Located on the Somali border along the Indian Ocean coast in northeastern Kenya. Protects the Boni Forest, which has been declared a biodiversity hotspot. The indigenous Awer and Watta people live in the forest. Due to its location, it is not recommended for tourists at present.

- Borana Conservancy - Combined cattle ranch and wildlife conservancy in the Laikipia Region north of Mount Kenya and contiguous with the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. Horse riding and game drives to see rhino and other wildlife.

- Buffalo Springs National Reserve - Located in the Samburu Region and the furthest north of Kenya's most popular reserves. Adjoins Samburu National Reserve (the two are separated by a river) and offers diverse wildlife in a mostly dry, semi-arid habitat.

- Central Highlands - Region located north of Nairobi in the center of Kenya that is defined by high altitude mountains including the Aberdares and Mount Kenya.

- David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust - Located in a reserved section of Nairobi National Park, the DSWT is a non-profit conservation organization that rescues and cares for orphaned elephants and rhinos, many of which are then released back to the wild in Tsavo East National Park. Visits are highly recommended.

- Diani Beach - Indian Ocean beach destination. Mostly upscale villas and all-inclusive resorts, though never overly crowded. White sands, palm trees, and beautiful blue waters with snorkeling, diving, fishing, and more.

- Dodori National Reserve - Situated just inland and north of Lamu along the northeast coast and not far from the Somalia border. Habitats include swamp, mangrove, woodland, forest, thorn veld, and coastal beach. Good numbers of wildlife, including a healthy population of topi. Seldom visited and not currently open for tourism due to the presence of Somali terrorists sometimes found in the region.

- Great Migration - The continuous movement of hundreds of thousands of animals, all of them blue wildebeest and Burchell's zebra, across the Masai Mara (Kenya) and Serengeti (Tanzania) ecosystem.

- Kakamega Forest - Located in western Kenya, it is the country's only tropical rainforest. Comprised of various, separately managed reserves, which protect a huge diversity of flora and is most famous for birding. Primates and other mammals also present. Under threat from large human population living around the forest.

- Kalama Community Conservancy - Adjoins Samburu National Reserve to the north and along with the neighboring West Gate Conservancy, provides tourism revenue for the local pastoralist Samburu people. Diverse wildlife and birding and easy day trips into Samburu/Buffalo Springs.

- Kisumu Impala Sanctuary - Located on the shores of Lake Victoria at the town of Kisumu. Small sanctuary offering 'a lakeshore walk with impalas'.

- Kiunga Marine National Reserve - Protects Indian Ocean waters and fifty calcareous offshore islands and coral reefs in the Lamu Archipelago in far northeast Kenya. Refuge for myriad sea life and birds. Excellent snorkeling, diving, sailing.

- Laikipia - Vast plateau situated between the Central Highlands and the semi-desert regions to the north. A patchwork of private and community-run conservancies and ranches offer superb wildlife experiences, as well as ranch activities and wildlife conservation.

- Lake Baringo - Freshwater lake in the North-Central Rift Valley. Excellent birding and a few good places to stay.

- Lake Bogoria National Reserve - Protects Lake Bogoria and land immediately surrounding the lake in Kenya's North-Central Rift Valley. The lake is often visited by enormous numbers of flamingos and a variety of large mammals also live around the lake.

- Lake Elmenteita - Small, saline, Central Rift Valley lake between Lakes Nakuru and Naivasha. Partially protected by the Soysambu Conservancy, with good plains game. Flocks of flamingos sometimes feed on the lake.

- Lake Magadi - Located in the Southern Rift Valley near the border with Tanzania. The lake's hypersaline waters are an important source of soda and the nearby Shompole Conservancy offers exploration and wildlife.

- Lake Naivasha - One of Kenya'a Central Rift Valley lakes. A popular eco-tourism destination, although it is not afforded protection via reserve or national park. Several private sanctuaries are located around the lake and Hell's Gate National Park is located very close to the south.

- Lake Turkana - Northern Rift Valley desert lake and the largest expanse of water in Kenya. Located in the far north and barely reaching into Ethiopia, with brackish water. Three national parks but seldom visited due to its remoteness.

- Lake Victoria - The largest lake in Africa, but only around 6% of the lake is located within Kenya. Not a heavily visited area for tourists, as there is little to offer other than a few island retreats.

- Lamu Archipelago - Indian Ocean islands located just offshore in remote northeast Kenya, very close to the Somali border. Lamu town is a popular cultural destination dating back to the 8th century.

- Lewa Wildlife Conservancy - Renowned wildlife conservation initiative that has successfully transformed farmland into a wildlife haven for rhinos, cheetah, zebra, lion, and many more species. Superb destination with top-notch safaris and game viewing.

- Masai Mara Conservancies and Group Ranches - Privately owned and managed land surrounding the Masai Mara National Reserve.

- Masai Mara National Reserve - Together with its adjoining private reserves, this is Kenya's premier wildlife destination. Popular for its incredible densities of plains game and attendant predators. Together with Tanzania's Serengeti, it is the location of the Great Migration of zebras and blue wildebeests.

- Mwea National Reserve - Small savanna ecosystem northeast of Nairobi and along the Tana River. Protects a diverse array of mammals, including elephant, giraffe, and buffalo. Birding, particularly for water birds and waders, is superb.

- Mwingi National Reserve - One of three reserves contiguous with Meru and Kora National Parks. Semi-desert scrub habitat except along the Tana River, where there is riparian forest. Good, though sparse wildlife and excellent birding. Few to no tourists.

- Nasolot National Reserve - Located a short distance west of South Turkana National Reserve and north of Mount Melo in northwest Kenya. Mainly a hiking destination, but there is some wildlife, though seeing the animals is challenging in mostly thick bush prevalent here. Almost no-one visits the reserve due to its remote location.

- Ngare Ndare Forest Reserve - Protects forest adjoining both Lewa and Borana conservancies to the south and offers additional land for use by elephants and other wildlife in the area. Maintained primarily by the local communities as the Ngare Ndare Forest Trust, under the supervision of Kenya Forest Service (KFS).

- Ol Pejeta Conservancy - Located in the Laikipia Region, this non-profit is one of several dual-purpose reserves that combines wildlife conservation with cattle ranching. Habitat is mainly grassland and Acacia scrub and wildlife here is diverse and abundant.

- Rahole National Reserve - One of three reserves contiguous with Meru and Kora National Parks. Semi-desert scrub habitat except along the Tana River, where there is riparian forest. Good, though sparse wildlife and excellent birding. Few to no tourists.

- Rift Valley (Central) - A popular wildlife destination in the center of Kenya's Great Rift, which spans the country north to south. The valley is home to rich grasslands and several important lakes, including Nakuru, Elmenteita, and Naivasha. Escarpments and volcanic highlands fringe the valley.

- Rift Valley (North-Central) - Directly north of the commonly visited Central Rift Valley are two lakes that are less often explored by tourists: Lake Baringo and Lake Bogoria, as well as Lake Bogoria National Reserve. Drier and much more harsh environment than the Central Rift Valley further south.

- Rift Valley (Northern) - A dry and remote area that extends all the way to the northern border and into Ethiopia. Dominated by Lake Turkana, the world's 4th largest saline lake. Several national parks and important archeological sites.

- Rift Valley (Southern) - The southern extent of Kenya's rift includes the hypersaline Lake Magadi and the northern tip of Lake Natron, which is mainly in Tanzania. A dry, sparsely populated, and interesting area, though not often visited.

- Samburu National Reserve - Along with its sister reserve, Buffalo Springs (the two are separated by a river), offers diverse wildlife in a semi-arid zone. Home of the colorful and rich Samburu people, who are conspicuous and welcoming to tourists.

- Shaba National Reserve - Located only a few kilometers east of Samburu and Buffalo Springs and offers an even more wild-feeling experience than its more visited neighboring reserves. Good wildlife viewing with very few visitors.

- Shimba Hills National Reserve - Situated near the coast in far southeastern Kenya. Good wildlife viewing but no lions (leopards are present though). Elephants, buffalo and a variety of other plains game. Popular day or short visit for anyone staying at Diani Beach on the Indian Ocean coast.

- Shompole Conservancy - Private venture run by the local Maasai people, located on the Tanzanian border at the northern tip of Lake Natron. Decent wildlife viewing.

- South Kitui National Reserve - Remote and seldom visited reserve adjoining Tsavo East National Park to the north. Plenty of wildlife and no tourists likely.

- South Turkana National Reserve - Located in northwest Kenya southwest of Lake Turkana. Rugged and desolate, with dense bush and some riparian forest. Plains game is scarce, although elephants migrate here between March and July. Seldom visited.

- Soysambu Conservancy - Converted ranch land created during the British colonial era now protects two-thirds of Lake Elmenteita's shores and surrounding land. Good plains game and several choices for accommodation.

- Tana River National Primate Reserve - Created to protect populations of two species of monkey, the Tana River red colobus and Tana River mangabey. The reserve has essentially been abandoned for years and its habitat has become seriously degraded. Efforts are underway to try and rescue the project.

- West Gate Community Conservancy - Adjoins Samburu National Reserve to the west and along with the neighboring Kalama Conservancy, provides tourism revenue for the local pastoralist Samburu people. Diverse wildlife and birding and easy day trips into Samburu/Buffalo Springs.

A white rhino with her calf in the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, Kenya (Copyright © James Weis).

Masai Mara Conservancies & Group Ranches

Outside of the boundaries of the Masai Mara National Reserve (MMNR) are numerous tracts of land owned by local Maasai tribes. Many, especially the ones directly bordering the national reserve, offer exceptionally good wildlife safaris on a par with, or arguably even better (due to lack of crowds) than inside the MMNR. Below is a list of the private conservancies around the MMNR.

- Enonkishu Conservancy - Enonkishu is located well north of and not directly bordering the MMNR.

- Kerinkani Group Ranch - Kerinkani is located directly west of the MMNR, along the escarpment and near the Tanzania border.

- Kimintet Group Ranch - Kimintet is located northwest of the MMNR, on the western banks of the Mara River. Excellent game viewing in its southern portion closest to the MMNR.

- Koiyaki Game Ranch - Koiyaki is located north of and not directly bordering the MMNR.

- Lemek Conservancy - Lemek Conservancy is located north of and not directly bordering the MMNR, but is along the Mara River.

- Lemek Group Ranch - Lemek Group Ranch is located well north of and not directly bordering the MMNR.

- Maji Moto Conservancy - Maji Moto is located well northeast of and not directly bordering the MMNR.

- Mara North Conservancy - Mara North directly borders the MMNR to the north and its western border is the Mara River; prime safari territory. Numerous safari camps with game drives in the conservancy and also into the MMNR

- Naboisho Conservancy - Naboisho directly borders the MMNR to the north and is in prime safari territory. Numerous safari camps with game drives in the conservancy and also into the MMNR.

- Naikarra Conservancy - Naikarra is located well east of and not directly bordering the MMNR.

- Olare Motorogi Conservancy - Olare Motorogi directly borders the MMNR to the north and is prime safari territory. Numerous safari camps with game drives in the conservancy and also into the MMNR.

- Olderikesi Group Ranch - Olderikesi directly borders the MMNR to the east along the Tanzania border.

- Oloirien Group Ranch - Oloirien is located directly west of the MMNR, along the escarpment. Some lodges atop the escarpment and game drives into the MMNR.

- Oloololo Game Ranch - Oloololo directly borders the MMNR to the northwest and has some Mara River frontage; prime safari territory. Very small landholding with some safari camps and game drives mostly into the MMNR.

- Ol Chorro Conservancy - Ol Chorro is located well north of the MMNR along the Mara River. Some safari camps.

- Ol Kinyei Conservancy - Ol Kinyei Conservancy is located northeast of the MMNR and is good safari territory. Small landholding with some safari camps and game drives mainly in the conservancy, but access to MMNR possible.

- Ol Kinyei Group Ranch - Ol Kinyei Group Ranch is located well northeast of and not directly bordering the MMNR.

- Siana Group Ranch - Siana is located directly east of the MMNR. Some safari camps with game drives on the group ranch and also into the MMNR.

- Talek Group Ranch - Talek directly borders the MMNR to the north. Small landholding with some safari camps and game drives mostly into the MMNR.

Read full details on the Mara Private Conservancies and its safari camps and lodges here.

A lioness is watched carefully by blue wildebeests in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy, Masai Mara, Kenya (Copyright © James Weis).

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations whose mission is to promote world peace and security through international cooperation in education, the arts, the sciences, and culture. The Convention concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage was signed in November 1972 and ratified by the 193 UN member 'states parties'.

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area which is geographically and historically identifiable and has special cultural or physical significance. To be selected as a World Heritage Site, a nominated site must meet specific criteria and be judged to contain "cultural or natural heritage of outstanding value to humanity". An inscribed site is categorized as cultural, natural, or mixed (cultural and natural). As of 2021, there were over 1 100 sites across 167 countries.

Kenya has seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- Fort Jesus, Mombasa (since 2011, Cultural) - Large fortress built by the Portuguese at the end of the 16th century to protect their control of the strategic port of Mombasa and the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes, which had previously been controlled by the Omani Arabs. The fort was constructed using coral, stone, and lime mortar and has imposing walls and five bastions. Its design reflects the military architecture of the Renaissance.

- Kenya Lake System in the Great Rift Valley (since 2011, Natural) - Comprises three alkaline lakes and their surrounding land: Lake Bogoria, Lake Nakuru, and Lake Elmenteita. The lakes are located on the floor of the central portion of Kenya's Rift Valley and they support a great diversity of bird and mammal species. Up to 4 million lesser flamingos move between these lakes for much of the year and are a major breeding ground for great white pelicans.

- Lake Turkana National Parks (since 1997, Natural) - Comprising three national parks located at Lake Turkana in far northern Kenya: Sibiloi, Central Island, and South Island. Turkana, often called the Jade Sea for its incredible color, is the most saline lake in East Africa and the largest desert lake in the world, surrounded by a desolate landscape. There are over 100 identified archeological and paleontological sites at Lake Turkana, with numerous volcanic flows and petrified forests. The island parks are breeding grounds for nile crocodile and hippopotamus and and the lake is a crucial stopover for migrating palaearctic birds.

- Lamu Old Town (since 2011, Cultural) - The Swahili town of Lamu is located on Lamu Island in the extreme north of Kenya's Indian Ocean coastline and has been continuously inhabited for over 700 years. The section called "old town" is the original settlement and is characterized by narrow streets and lovely old architecture influenced by a mix of Arabic, Persian, Swahili, Indian, and European styles. The town has managed to retain much of its traditional culture.

- Mount Kenya National Park/Natural Forest (since 1997, Natural) - Mount Kenya, a massive extinct volcano, is Africa's second tallest peak (17 057 feet/5 199 meters) straddling the equator in Central Kenya. There are four secondary peaks and 12 remnant glaciers, which are all retreating rapidly. The property also includes Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and Ngare Ndare Forest Reserve, located to the north, and the two properties are connected by a wildlife corridor, which is crucial for numerous mammals, and in particular elephant. The forested foothills and valleys of the lower slopes of the mountain are also incorporated in the site.

- Sacred Mijikenda Kaya Forests (since 2008, Cultural) - Remains of numerous fortified villages, known as Kayas, built in the 16th century and belonging to the Mijikenda people. The villages were all abandoned by the 1940s, and are spread out inland and around present-day Mombasa. The sites are now regarded as the sacred abodes of their ancestors and are maintained by a council of elders. The small pockets of forest surrounding the various Kayas are now almost the only remains of a once extensive coastal lowland forest in present-day Kenya.

- Thimlich Ohinga Archaeological Site (since 2018, Cultural) - Situated near the town of Migori in southwest Kenya and very close to Lake Victoria, Thimlich is the largest and best preserved example of an early pastoral community 'ohinga' (enclosure). The site includes typical examples of dry stone walled enclosures that served as a protective fort and enclosure for people and livestock, dating back to sometime in the 16th century.

View into the Rift Valley in Kenya.

Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. It was the first of the modern global nature conservation conventions, negotiated during the 1960s by countries and non-governmental organizations concerned about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for birds and other wildlife. The convention is named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, where the convention was signed in 1971.

Presently there are some 75 member States to the Ramsar Convention throughout the world which have designated over 2 300 wetland sites onto the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance.

Kenya has six sites designated as Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Sites) as follows.

- Lake Baringo - An important freshwater lake in Kenya's North-Central Rift Valley. Ol Kokwe Island is the remnant of a small volcano. The lake is fed by freshwater inflows from nearby hills and provides crucial habitat for around 500 species of birds and seven freshwater fish species, one of which is endemic. The lake is also habitat for hippo, crocodile, and a variety of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. Human activities include fishing, water usage for drinking and irrigation, and boating. (121 sq miles/315 sq kms)

- Lake Bogoria - Another of Kenya's North-Central Rift Valley lakes, Bogoria has alkaline waters that are dominated by hot springs. The lake is a critical refuge for lesser flamingos, which at times gather in the hundreds of thousands to feed. The lake and surrounding acacia woodland are protected as a national reserve and are home to a variety of mammals. The region around the lake is semi-arid, but the lake's water levels are consistent, which is crucial, particularly during times of drought. Human activities include pastoralism by the local Tugen and Jemps tribes, as well as tourism. (41 sq miles/107 sq kms)

- Lake Elmenteita - A shallow, alkaline, saline lake in the Central Rift Valley that supports healthy environment for blue-green algae and diatoms. The algae is a favored food for the lesser flamingo, which gather here in large numbers to feed. The lake is also a favored breeding ground for great white pelicans. Human activities include tourism, subsistence irrigation, water for livestock, and grazing, though most of the land directly surrounding the lake is protected. (42 sq miles/109 sq kms)

- Lake Naivasha - A high altitude, freshwater crater lake in Kenya's Central Rift Valley that includes a river delta and separate smaller lake dominated by blue-green algae and soda tolerant vegetation. There is no visible outlet, but because the lake's water is fresh, there is assumed to be an underground outflow. Naivasha provides habitat for over 400 species of birds and a sizeable population of hippo. Other mammals living along the lakeshore include buffalo and waterbuck. Human activities include livestock ranching, agriculture, fishing, freshwater usage, and tourism. Kenya is a leading exporter of cut flowers, and the area around the lake is used for floriculture, which employs thousands of Kenyans, but poses a major threat due to its use of pesticides and fertilizer. (116 sq miles/300 sq kms)

- Lake Nakuru - A shallow, strongly alkaline Central Rift Valley lake with surrounding woodland and grassland. The lake is fed by four seasonal rivers and one perennial river. Habitats include seasonally flooded and dry grassland, swamps, riparian forest, sedge marsh, and various types of scrub. The lake and surrounding land are protected by Lake Nakuru National Park. The park protects numerous endangered mammals, including black rhino, as well as regionally endangered bird species, including the gray-crested helmetshrike. Human activity is primarily tourism inside the national park, but outside the park there is large-scale agriculture and cattle ranching. (73 sq miles/188 sq kms)

- Tana River Delta - Second most important estuarine and deltaic ecosystem in East Africa. Includes a variety of habitats, including freshwater, estuary, mangrove, marine, marine/brackish intertidal, beach, and marine shallows. Supports rich biodiversity including shrimps, bivalves, prawns, fish, and five species of marine turtle. Mammals include elephants Tana River red colobus, Sykes' monkey, and Tana mangabey. Serves as a critical wintering and feeding grounds for numerous migrating waterbirds. Human activities include fishing, small-scale agriculture, wood collecting, tourism, and research (turtle and dugong). (631 sq miles/1 636 sq kms)

Great (white-breasted) cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo lucidus) at Lake Naivasha. The lake is one of Kenya's six Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance.

Urban Areas

Kenya has four significant urban areas, with two being quite large in terms of population. Info on each follows below.

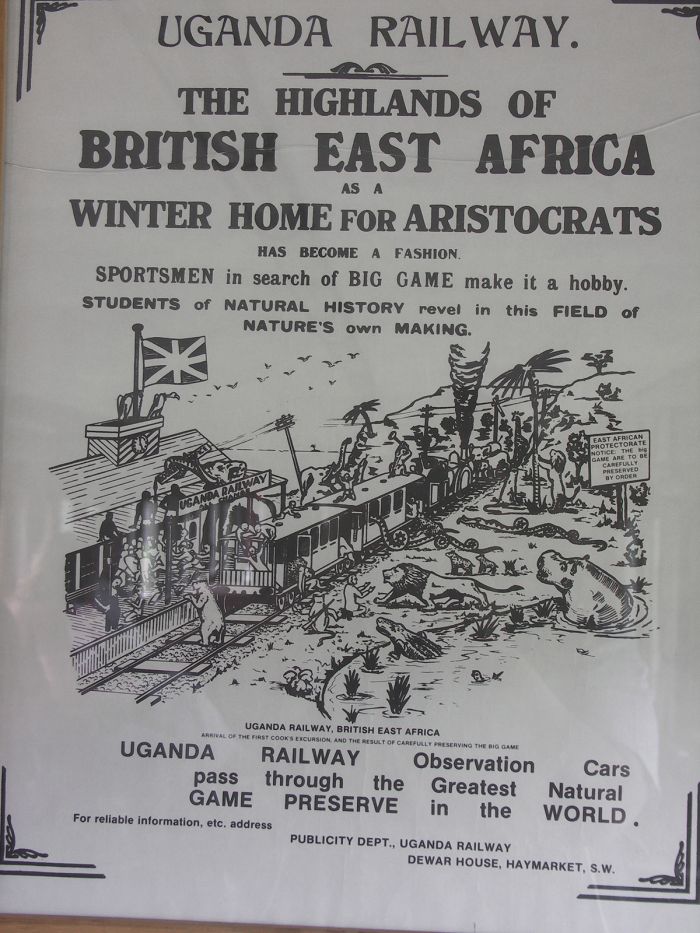

- Kisumu - Kenya's third most populous city on the shores of Lake Victoria. The original terminus of the Uganda Railway line from Mombasa. Not much to see or do.

- Malindi - Historic town on the Indian Ocean coastline. Today the town is primarily a tourism center, especially with Europeans, who come for the beach and water sports.

- Mombasa - Significant port city on Kenya's Indian Ocean coast. The country's second largest city by population (after Nairobi). Long history dating back to around 900 AD. Not considered a tourist destination.

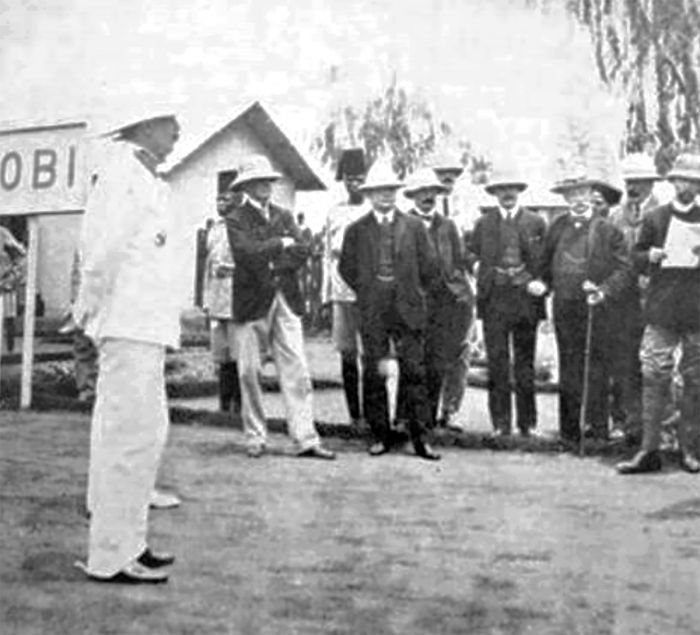

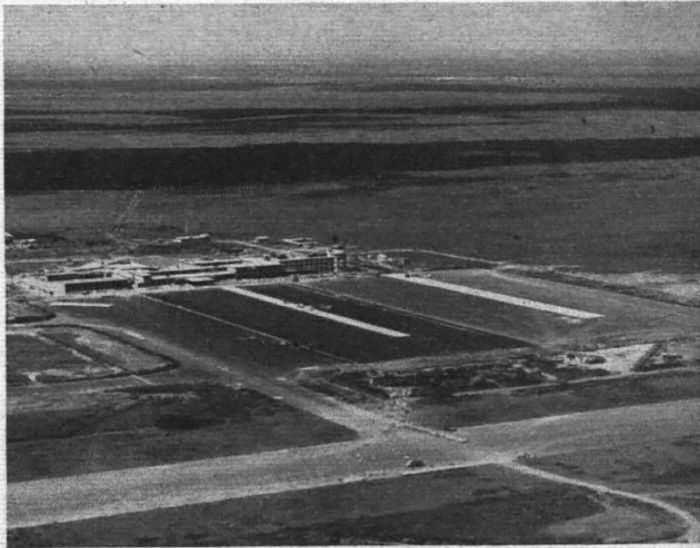

- Nairobi - Kenya's capital and largest city, as well as a major international arrival gateway to all of East Africa. The Nairobi National Park, situated south of the city, is surprisingly good for wildlife safaris.

Evening view over Nairobi, Kenya's capital city.

Masai Mara

The Masai Mara is located along Kenya's southern border with Tanzania and is contiguous with that country's Serengeti region. The Kenya side of this large ecosystem includes the Masai Mara National Reserve (MMNR), as well as numerous private conservancies that surround the MMNR on the west, north, and east.

Kenya's Masai Mara is certainly the country's top wildlife destination and one of the most popular in all of Africa. Often referred to simply as 'the Mara', these extensive grasslands are part of a greater ecosystem that spans across Southeast Kenya and into northeast Tanzania's Serengeti National Park.

The combined Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, which includes adjoining parks and private reserves, covers some 15 000 square miles (39 000 sq kms) and is a haven for huge numbers of large mammals.

Kenya's Masai Mara is a very good place to see cheetah.

The Great Migration

The Mara-Serengeti ecosystem is the setting for one of the animal kingdom's greatest spectacles, the 'Great Migration'. Throughout the year, some two million herbivores, primarily blue wildebeests and Burchell's (or plains) zebras complete a clockwise cycle around the Serengeti and Masai Mara in a never ending search for good grazing.

The movement of the herds is coordinated and yet imprecise, with the timing of their arrival somewhat determined by local rainfall. The herds are always very spread out due to their number, but in general, the bulk of the animals spend around three months (from late July thru early October) on the Kenya side (Masai Mara) of the grasslands and the other nine months in Tanzania's Serengeti, which covers a far greater portion of the overall ecosystem.

The 'Great Migration' of blue wildebeest and zebra is a spectacular event to experience.

There are no substantial fences in the Mara-Serengeti, so to the animals, it is just one large environment with the only barriers being rivers. The biggest obstacle, and one that brings safari enthusiasts to the region time and again, is the dramatic scenes that unfold when big herds of wildebeest and zebras swim across the Mara River. Hungry crocodiles, including some that are massive beasts and have not eaten anything substantial for many months, lie in wait to catch their long awaited meal.

Masai Mara Resident Wildlife

Besides the annual and endless trek of the wildebeest and zebras, the Mara is home to a multitude of other resident wildlife, which may move around some, but do not follow the Great Migration.

Other commonly seen plains game in the Mara include elephant, giraffe, Thomson's gazelle (or 'tommies', as they are sometimes called), topi, eland, Coke's hartebeest (a local subspecies of hartebeest also known as 'kongoni'), roan antelope, Grant's gazelle, common reedbuck, waterbuck, warthog and more. A small population of black rhino still live in the Mara.

Giraffes in Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve.

Predators, especially big cats, are found throughout the Mara-Serengeti, with the habitat being very suitable for cheetah, which need wide open plains to run down their prey. Cheetah are a highlight to be sure, but there are also good populations of lion, spotted hyena, leopard, two species of jackal (black-backed and side-striped), and serval.

The 'Mara Triangle'

The Mara River separates the reserve into two separately managed sections: the main reserve, which lies east of the river, the a triangular-shaped section of land known as 'the Mara Triangle', which lies west of the river and is bounded by a steep escarpment at the western edge of the overall reserve.

Almost all the safari accommodations in the reserve are on the eastern side of the river, with only a small number of lodges and camps in 'the triangle' or outside the reserve atop the escarpment (these have amazing views over the reserve).

A spotted hyena searches for potential prey amongst the herds of blue wildebeest (Copyright © James Weis).

Visiting the Masai Mara

Visitor accommodations in the Masai Mara Reserve are numerous and range between rustic, bucket-shower 'bush' camps, to extravagant five-star luxury lodges, with pricing also accordingly covering a large range.

Game drives are the main activity in the Mara, with both a morning and an afternoon drive being the norm. Full-day drives are also an option, with a packed lunch, particularly for those that wish to wait alongside the Mara River in hopes of seeing a river crossing.

Other activities in the Mara include the very popular hot-air balloon safaris, which depart daily just before sunrise and offer an incredible experience. The views over the Mara from above give a totally different perspective of the vastness and diversity of habitats in the reserve. After the ride, which lasts 60-90 minutes, guests are treated to a Champagne breakfast and then the morning game drive ensues.

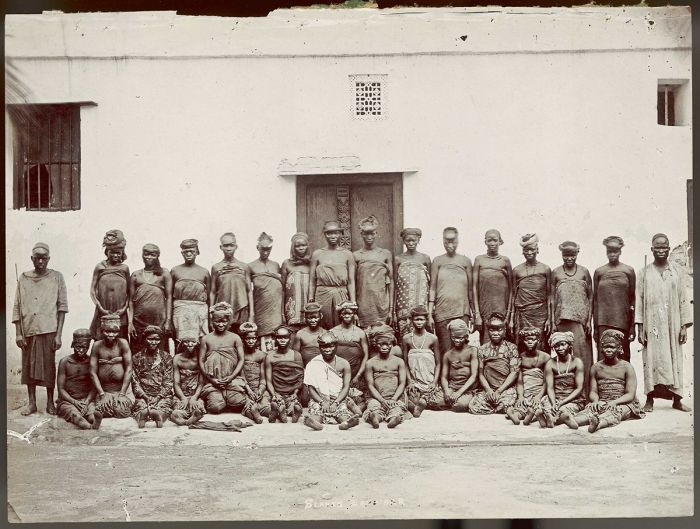

Another component of visiting the Masai Mara is the Maasai people themselves, after whom the reserve is named. Most of the safari guides are of Maasai heritage, as are almost all the staff and workers in the safari camps and lodges.

The Maasai have lived in the region for centuries and their characteristic tall, slender shapes, adorned in the traditional colorful 'kikoi' (body wrap) and beaded jewelry are a common sight in the Mara. Visits to a Maasai village are available from almost any safari camp.

The Maasai people are present throughout the region and visiting a local village provides a look into their traditional way of life.

Choosing when to visit the Mara is important, as it will determine much of your experience.

The rains in the Masai Mara are most common between November and May, with two somewhat distinct seasons: the 'short rains', which fall in November and December, followed by a drier period from January to sometime in March, followed by the 'long rains' in March and April. The short rains in November/December are not usually anything to worry about in terms of interfering with safari activities, but March thru May is the wettest time and rains occur almost every day.

Another consideration on timing one's visit to the Masai Mara is the Great Migration. The annual movement of wildebeests and zebras are at their peak from late July until sometime in October, so this is an ideal time to be in the Mara for viewing this spectacle. That said, the game viewing is excellent outside of these peak migration months, with all of the predators, other plains game, and even some of the wildebeests and zebras present throughout the year. Keep in mind that the migration months in the Mara are also the busiest in terms of visitors.

Surrounding the Masai Mara National Reserve are a good number of privately managed reserves that offer more accommodation and game viewing. Read more below.

Read full details on the Masai Mara National Reserve and its safari camps and lodges here.

Early morning hot-air balloon safaris are an exciting way to get a bird's eye view of the Masai Mara.

Masai Mara Private Conservancies

The land bordering the Masai Mara National Reserve (MMNR) is owned by various different communities of Maasai people and over the last two decades, the landowners have organized to create private reserves, mainly to take advantage of tourism revenue opportunities. Many of these private reserves (some are called conservancies, others are called group ranches) have signed leases with safari companies, allowing them to build safari camps and market tourism activities to travelers.

This tourism model, in which the community shares in tourism revenue and/or receives monthly lease payments, was based on the successful model used in Botswana. The land-owning Maasai communities around the national reserve earn tourism revenue, which allows for more visitors to come to the Mara, while investing these communities in the sustainable conservation of the wildlife and land.

The Mara private reserves, particularly those that directly border the MMNR, offer a safari experience that matches or arguably exceeds that within the national reserve, as these private reserves are generally less crowded and have abundant wildlife.

The private conservancies bordering the Masai Mara Reserve offer excellent game viewing with far fewer tourists.

Only guests staying at one of the safari camps in a specific private reserve are permitted to be on safari there, while the MMNR itself is open to anyone paying the gate fees, so the reserves generally offer more exclusive experience with far fewer people and never any crowds. Day visits into the MMNR are still an option to guests staying in one of the private conservancies.

Wildlife in the Mara conservancies is essentially the same as in the national reserve, and the Great Migration reaches north into some of the conservancies as well. The conservancies directly bordering the national reserve are generally the best for wildlife viewing, as well as those along the Mara River.

Lion, leopard, and cheetah are good bets in many of the conservancies, including Mara North, Olare Motorogi, Talek, and Naboisho. General plains game is superb in those conservancies as well. The further outlying conservancies also have good wildlife, though game viewing is generally better closer to the national reserve. The conservancies further to the north and northeast are still developing tourism, but are on their way and should provide similar game viewing experiences once they become more established.

A large 'pod' of hippos in the Mara River, Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya.

Visiting the Mara Conservancies

Safari accommodations are available in many of the conservancies, particularly in those mentioned in the previous paragraph. Game drives in the conservancies are offered exclusively to safari camp guests and the land is off limits to anyone not staying in the same conservancy (except in special cases where neighboring conservancies allow limited access to each other).

Guests staying in the conservancies may also pay to drive in the Masai Mara National Reserve if so desired; this is particularly common during migration season (late July thru September) when Mara River crossings occur in the national reserve.

Timing your visit to the Masai Mara is discussed just above.

Read full details on the Masai Mara Private Conservancies and its safari camps and lodges here.

A Maasai man watches as herds of grazing animals go about their day on the grasslands of the Masai Mara.

Amboseli National Park

Located very close to the Tanzanian border, Amboseli is famous for two things: elephants and its amazing views of Africa's tallest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro, which lies just south of the park in Tanzania.

Amboseli has a colored past, as the area that is now national park was historically used by the Maasai people for grazing and watering their cattle. When the park was declared in 1974, the Maasai were formally excluded from their traditional land, causing terrible conflict. The Maasai retaliated by killing nearly all of the black rhinos and lions in Amboseli, which greatly damaged tourism to the park. Eventually the government built a water pipeline for the Maasai cattle, after which the Maasai gave up their land.

The park is named for the Maasai word meaning "salty dust" and the park is sometimes referred to as the 'Maasai place of dust'. Those who have visited can attest to the accuracy of this description. Much of Amboseli is covered with very fine saline, volcanic ash, which was deposited by ancient eruptions of Mount Kilimanjaro. The movements of animals and wind sometimes creates interesting 'dust devils', which swirl across the plains.

Elephants in Amboseli National Park with Mount Kilimanjaro as a backdrop.

Despite the dust and its relatively small size, Amboseli has a diversity of habitats, including large freshwater swamps and marshes (fed by underground streams from Kilimanjaro), Acacia scrub, Acacia woodland, and open grassy plains. Lake Amboseli is typically completely dry and only ever fills during substantial rains and even then, it is quiteshallow. When the lake has water, it attracts large numbers of pelicans and flamingos.

Mount Kilimanjaro provides a spectacular backdrop to Amboseli's wildlife and on clear days, when the mountain is visible, images of elephants walking in long lines across the plains with the mountain filling the background are the stuff of dreams for anyone with a camera. Kilimanjaro looms huge to the south, but is often shrouded by clouds and/or dust at its upper elevations.

The keystone species at Amboseli is the elephant, which are easy to see and will often provide up-close views, as they are very used to 4x4 vehicles and are almost always very relaxed around them. The calm temperament of Amboseli's elephant population, which includes some old bulls with sizable tusks, and the incredible backdrop provided by Mount Kilimanjaro, makes the park a candidate for Africa's top place for elephant viewing and photography.

Amboseli can be quite dusty, but this provides for interesting images (Copyright © James Weis).

Besides the elephants, Amboseli is home to a variety of other plains game, with giraffe, Burchell's zebra, and buffalo being the most common. Other large mammals living in Amboseli include blue wildebeest, impala, Grant's gazelle, Thomson's gazelle, and gerenuk. The odd-looking gerenuk is a slender antelope with a very long neck, which has adapted to feeding on vegetation most other antelope cannot reach by standing upright on its hind legs and stretching its neck upward. Baboon are also present in good numbers in the forested and wetter areas of the park.

Predators in Amboseli are tough to see, other than spotted hyena and black-backed jackal. There area some lions in the area of the park, and they can sometimes be seen if you are lucky. Leopard are also present, but are very elusive and seldom seen.

Wildlife viewing in Amboseli is good all year, but is best from June thru October and again in January/February. Like much of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, there is a short rainy season that occurs in November/December and a longer rainy period from late March thru May. As discussed above, the dry season is very dusty and hazy, but wildlife viewing is very good.

Lake Amboseli fills seasonally in some years and when it does, it attracts flamingos and other waterbirds.

Despite the promise of rain during the two rainy periods, these can be wonderful times to visit Amboseli, as the landscape transforms from brown to green and Lake Amboseli may fill with water, attracting flamingos, pelicans and other migrant bird species, making for incredible imagery. Elephants and other large mammals may disperse outside the park if the rains are good in the region.

There are a selection of safari camps and lodges located inside Amboseli National Park, as well as some outside the park that are still close enough to allow for easy day trips into the park.

Read full details on Amboseli National Park and its safari camps and lodges here.

A lone bull elephant in Amboseli with Tanzania's Mount Kilimanjaro in the distance (Copyright © James Weis).

Tsavo

(Including two national parks and one national reserve: Tsavo West NP, Tsavo East NP, and South Kitui NR)

Located along the Tanzanian border in southeast Kenya, Tsavo's total protected area stretches northward for some 170 miles (275 kms) and covers an area of 8 743 square miles (22,645 sq kms). The parks were originally one entity, but were divided by the Mombasa-Nairobi Railway and road and so became two national parks in 1948. With Tsavo West on the southern side and Tsavo East to the north. The small and very remote South Kitui National Reserve is situated at the far north of the area.

The Tsavo region was immortalized by John Henry Patterson's 1907 book, The Man-eaters of Tsavo, which details the authors' experiences while he oversaw the construction of the Uganda Railway through British-controlled land in 1898. The book recounts the attacks on railway workers by two male lions, which reportedly killed and devoured 135 workers in under one year's time before the author was able to shoot the lions.

Male lions in Tsavo, Kenya.

In more recent times, Tsavo has experienced periods of drought and horrible persecution of its wildlife, especially elephants, at the hands of poachers. The 1970s were a time of mass poaching throughout much of Africa and Tsavo was particularly hard hit. By the 1990s, Tsavo's elephants had been reduced from around 35 000 in the late 1960s to only 6 000 animals. Tsavo's once numerous black rhinos were on the verge of local extinction.

In 1992, the Kenya Wildlife Service performed a globally publicized burning of its ivory (elephant tusk) stockpile and implemented a new "shoot on sight" policy regarding poachers, which effectively put an end to poaching in Tsavo. Elephant numbers today are about 12 000 in Tsavo and black rhinos number an estimated 150, most of which are under full-time guard in the protected Ngulia Rhino Sanctuary in Tsavo West.

In terms of differentiating the two parks, Tsavo West has more sources of water, with several swamps, Lake Jipe, and the Mzima Springs. It is also generally much more mountainous, which makes this park very popular for rock climbing enthusiasts. In terms of tourism, Tsavo West has a far more developed road network and more accommodations, so it receives by far the most visitors, with the more remote and wild Tsavo East rarely included on itineraries.

Burchell's zebra are commonly seen in the national parks of Tsavo.

Tsavo West National Park

Although Tsavo West covers a vast area of 3 500 square miles (9 065 sq kms), only the much smaller area between the Tsavo River and the Mombasa-Nairobi road (the developed area covering less than 15% of the park) receives many visitors. This area has the best game viewing due the combination of the rich volcanic soil and the Tsavo River frontage.

The dominant habitat in Tsavo West is Acacia scrub, which is very thick in most areas, as well as Acacia woodland. The areas along the Tsavo River have patches of riparian woodland, with palms and other large trees fringing the waterway. There are also areas of open plains, with volcanic cones interspersed seemingly all over.

Wildlife in Tsavo West is abundant, with Maasai giraffe, Burchell's zebra, buffalo, impala, Grant's gazelle, and elephant all fairly easy to encounter. The elephants in Tsavo often appear to be a reddish color, which is due to the color of the volcanic earth that they use for covering their skin as protection from the sun and insects.

All of Africa's Big Five (lion, leopard, rhino, elephant, buffalo) are found in Tsavo, with elephant, buffalo, and lion a good bet to see, while leopard are more challenging, as they are everywhere. Black rhino are best seen in the Ngulia Rhino Sanctuary, which is a cordoned-off area that still allows the rhinos to roam free.

Maasai giraffes in Tsavo.

Other common animals in Tsavo West include spotted hyena, black-backed jackal, warthog, and baboon. Less common are lesser kudu, Coke's hartebeest, eland, and fringe-seared oryx.

One of the biggest attractions in Tsavo West is Mzima Springs. Mzima's waters are filtered by the porous underground lava rock, making them crystal clear. The site has two large pools of water, which are connected by a cascade of rapids that are fringed by palms.

Mzima's upper pool is favored by hippos, while the more open lower pool is where most of the crocodiles are found. The top pool also has an underwater viewing room, where one can get otherwise impossible views of hippos (and sometimes crocs) in their environment below the surface. Mzima also has walking trails that are well marked and very informative in terms of learning about the various trees and other plants along the way.

Read full details on Tsavo and its safari camps and lodges here.

Leopard are never easy to find, but are present in areas with good cover in both of Tsavo's national parks.

Tsavo East National Park

Kenya's largest national park, Tsavo East covers 5 290 square miles (13 747 sq kms) on the northeastern side of the Mombasa-Nairobi road, which separates it from its sister park, Tsavo West.

Although Tsavo East is massive, only the area south of the Galana River is used regularly for safaris, while the northern section, with very few vehicle roads, seldom sees any visitors. Those who do visit Tsavo's East will surely feel as if they are the only people in the park, with hours, if not an entire day, that can be spent exploring without ever passing another vehicle.

The park receives water from the perennial Galana River, which crosses Tsavo East en route to the Indian Ocean, as well as from the seasonal Voi River to the south. The park's wildlife depend on these rivers for water and the best game viewing is usually along the rivers and in the riparian woodlands that fringe these waterways.

Elephants coming to drink in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya.

Tsavo East's terrain is dominated by a seemingly endless flat plain of open bushland and Acacia scrub. The Yatta Plateau rises just east of the park's western boundary, which is defined by the Galana River.

Tsavo East is home to four of Africa's Big Five (lion, leopard, elephant, buffalo), with elephant and buffalo being the most common and easiest to find. Lion and leopard are here and are best seen along the rivers, while black rhino are only found in Tsavo West's Ngulia Rhino Sanctuary.

Other wildlife that can be seen is the same as in Tsavo West, and includes Maasai giraffe, impala, Burchell's zebra, Grant's gazelle, eland, oryx, Coke's hartebeest, spotted hyena, black-backed jackal, baboon, and warthog.

One very popular spot in Tsavo East is Lugard Falls, along the Galana River. These rapids lead to several pools just downstream that usually have hippos and crocodiles.

The gerenuk (Litocranius walleri) is a range-restricted antelope found in Tsavo. It has adapted such that it often feeds while standing on only its two hind legs.

Tsavo's elephants were badly persecuted by poachers in the 1970s and 1980s, but today Tsavo is a relatively safe place for them. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (DSWT) has been paramount in the conservation of Kenya's elephants and their two release facilities (for rehabilitated rescues) are both located in Tsavo East. Visiting their facilities (prior arrangement required) is a wonderful experience. The DSWT rescue center is in Nairobi and this too is a highly recommended activity for anyone with a few hours in the city.

Accommodation in Tsavo East includes a handful of camps in both the south (those near the Galana River are a good option) and in the north, where the Ithumba camps are great for those that want to experience the true wilderness of the park's northern section. The small town of Voi, which lies just outside one of the park gates along the Voi River, also offers some accommodation.

Read full details on Tsavo and its safari camps and lodges here.

Tsavo offers good dryland birding; here a group of vulturine guineafowl (Acryllium vulturinum).

South Kitui National Reserve

The extremely remote far north of the Tsavo region includes the South Kitui National Reserve, which adjoins the northern boundary of Tsavo East National Park.

The reserve is characterized by open grassland, Acacia scrub, and patches of thick bush. Wildlife in the reserve is essentially the same as the Tsavo parks, with elephant a good bet.

South Kitui is seldom visited due to its very remote location and there is no permanent accommodation.

Elephants in Tsavo East National Park.

Chyulu Hills National Park

Named for the highland ridge of hills that spans roughly 60 miles (100 kms), the Chyulu Hills are one of Kenya's most beautiful destinations. The hills are formed by a volcanic ridge that rises to a maximum elevation of 7 180 feet (2 188 meters), creating a transition zone between the low elevation plains of Tsavo and Amboseli.